Guest Post: Making Obama’s Peacekeeping Commitments a Reality

More on:

Amelia M. Wolf is a research associate in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

While chairing Monday’s Leaders’ Summit on Peacekeeping, President Obama called on UN member states to increase their troop contributions, improve protection of civilians, and reform and modernize peace operations. The intent and outcome of the meeting is a positive step toward strengthening the ability of UN peacekeeping to work more effectively in complex environments. However, there are many issues left unaddressed, and what matters most is what comes next.

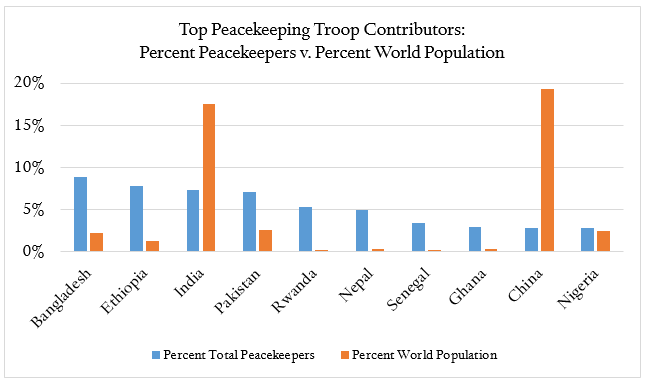

First, the U.S. contributions announced by President Obama are not enough. Obama vowed to “double” the number of U.S. military officers in UN peacekeeping operations. Given that the United States currently contributes six military experts and thirty-four troops—less than .04 percent of military personnel—major contributors shouldn’t be fooled by Obama’s promise. In fact, the top ten troop contributing countries account for 54 percent of troops, but make up just 46 percent of the world’s population.

If the Obama administration genuinely believes that “too few nations bear a disproportionate burden of providing troops,” then it should be more willing to commit more U.S. military experts and troops to the cause. This would require breaking down barriers within the armed services that make it difficult for military officers to serve in peacekeeping operations, even though the desire exists among them.

As Paul Williams, professor of international affairs at George Washington University, wrote in a recent Council on Foreign Relations report, greater troop contributions from the United States would have three primary benefits: demonstrate the country’s commitment to the idea that peace operations are a global responsibility and intrinsic to conflict management and mitigation; strengthen Washington’s ability to exercise leadership by leading by example; and increase the effectiveness of missions. Additionally, it would increase U.S. military and intelligence awareness of other operating environments and enhance bilateral relationships with peacekeeping units from other countries.

An additional goal for the Obama administration should be to ensure gender diversity in future contributions. Half of the upcoming “doubling” of U.S. military contributions—though a meager total of forty—should be reserved for women, and the United States should also strongly advocate that countries’ contributions be more gender diverse. Some countries already took initiative. India and Bangladesh have deployed all-female police units, and Rwanda promised to do the same at Monday’s summit. However, progress has been slow. Over the past five years, women’s involvement in military missions has increased by less than 1 percent, and the number of female police officers has increased by just 1.8 percent.

Second, given that the UN peacekeeping budget is still inadequate, the United States can and should use its leverage as the top funder to pressure other states to increase their financial contributions. The United States provides 28 percent of the peacekeeping budget. This might seem high. However, countries are supposed to make contributions to the United Nations based on their percent of global GDP and, among the top ten funders of peacekeeping operations specifically, the United States is not an outlier—nine punch more than their own weight. The top ten funder account for 71 percent of funding, but just 53 percent of the world GDP.

Third, as facilitator of the UN peacekeeping summit, the Obama administration should encourage UN member states to engage in a discussion on how UN Security Council mandates should evolve with operating environments that have significantly changed since the first mission in 1948. In a June report, the High-Level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations found that, “a number of peace operations today are deployed in an environment where there is little or no peace to keep.” In addition to traditional peacekeeping tasks, mandates for peace operations now include counterinsurgency, state-building, atrocity prevention, and even counterterrorism. “The problem,” Williams says, “is that all these different types of activities, of course, require really different types of training, different types of capabilities.”

The pledges of an additional thirty thousand troops and police is a monumental step forward, but their ability to successfully fulfill mandates will be hindered if they are not adequately trained for the range of operations that are now categorized as peace operations. This problem is evident in the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). One senior UN official anonymously stated, “We have very naively gone into northern Mali, into a very non-permissive environment, without understanding the implications,” and warning that the result would be “lots of U.N. peacekeepers killed…an ignominious withdrawal and total mission failure.”

So far, discussions on mandates have primarily taken place in the Security Council Working Group on Peacekeeping Operations, which has been chaired by Chad since May 2015. Before Chad’s chairmanship ends on December 31, the United States should consult with Chad, Secretary-general Ban Ki-moon, and other working group participants to ensure that the incoming chair has the diplomatic capacity and is willing to prioritize this issue.

The Obama administration’s initiatives are on the right track to strengthening the capacity and abilities of UN peacekeeping operations. Its commitments made at Monday’s summit and in a Presidential Memorandum on Support to UN Peace Operations—including additional air and naval logistical support, training, protection against IEDs, and enhanced technologies—will provide peacekeeping missions with more timely and essential supplies. Notably, proposals in the president’s memorandum closely reflect recommendations proposed by Williams’s report, Enhancing U.S. Support for Peace Operations in Africa. The Obama administration has also supported peacekeeping in other capacities, such as the 2009 New Horizon initiative to develop operational standards for UN peacekeepers, the Senior Advisory group that led to reforms in 2012, and the White House’s African Peacekeeping Rapid Response Partnership (APRRP) proposal.

Garnering member state contributions is just the first step of many toward ensuring that peacekeepers have the “the training and the forces and the capabilities and the global support they need to succeed in their mission,” as Obama said. It is the responsibility of the United States to ensure that subsequent steps are taken to clearly differentiate between increasingly diverse peacekeeping mandates and ensure that peacekeepers are equipped and trained to succeed in those missions. One year from now, at the 2016 UN General Assembly, the Obama administration should be prepared to evaluate not only how peacekeeping contributions have grown, but whether they have better enabled peacekeepers to complete their missions.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store