Osama Bin Laden’s Death: One Month Later

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Micah ZenkoSenior Fellow

Tomorrow marks the one month anniversary of President Barack Obama’s appearance before the nation to announce that “the United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama bin Laden.” According to Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, on the evening of the raid, senior officials in the White House situation room “all agreed that we would not release any operational details from the effort to take out bin Laden. That all fell apart on Monday—the next day.” Total secrecy, however, was never possible given the historic importance of the story, insatiable demand for news coverage, and willingness of unnamed U.S. government sources to leak.

Tomorrow marks the one month anniversary of President Barack Obama’s appearance before the nation to announce that “the United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama bin Laden.” According to Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, on the evening of the raid, senior officials in the White House situation room “all agreed that we would not release any operational details from the effort to take out bin Laden. That all fell apart on Monday—the next day.” Total secrecy, however, was never possible given the historic importance of the story, insatiable demand for news coverage, and willingness of unnamed U.S. government sources to leak.

For a covert operation conducted by a military unit (the Navy SEALs) that the Department of Defense does not acknowledge, a staggering number of operational details have emerged. (As best can be determined, the only U.S. official who discussed the Navy SEALs’ role was Vice President Joseph Biden, when he boasted two days after the operation of “the just almost unbelievable capacity of his Navy SEALs and what they did last Sunday.”) Within forty-eight hours of the successful raid into Abbotabad, Pakistan, Crown Publishers announced that terrorism analyst Peter Bergen would write “an immersive, definitive account of the operation that killed the world’s most wanted man.” While we wait for Bergen’s report, here are my thoughts on several aspects of the operation, which was reportedly code-named Neptune Spear.

Intelligence Collection and Analysis

U.S. officials have not explicitly described how the information was obtained that led to Bin Laden’s trusted couriers, Abrar and Ibrahim Said Ahmad. Reportedly, certain intelligence threads were extracted from two suspected terrorists who were tortured while in the CIA’s extraordinary rendition program, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Abu Faraj al-Libbi. An unnamed senior intelligence official described the intelligence process as: “Multiple detainees debriefed over a number of years, and then it was a composite picture of the courier network and this particular courier that we were interested—that led us to this compound.” Once the courier was traced to the Abbotabad compound, every conceivable means available to the U.S. intelligence community was employed to determine who lived inside. Satellites controlled by the National Reconnaissance Office and the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency mapped the surrounding terrain and the layout of the compound. The CIA reportedly flew a stealth surveillance drone, the RQ 170 Sentinel, before and during the mission. The CIA also operated a nearby secret facility where case officers and recruited informants provided on-the-ground surveillance of the daily activities of the occupants of the compound.

Analyzing the collected data fell primarily to the CIA, with the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Leon Panetta later highlighting the work of “the officers of our CounterTerrorism Center and Office of South Asia Analysis.” One operational concern was the possibility of the Pakistani military learning of the intervention, and engaging the Navy SEALs in a firefight. However, according to Panetta “We’d red-teamed that issue to death,” and were comfortable that Pakistan would not know in time. The larger analytical concern was determining if Bin Laden was actually inside the compound. Panetta put the likelihood at 60 to 80 percent, while other CIA officers believed the odds were no better than 50-50.

Interestingly, this threshold was comparable to the likelihood that Bin Laden could be identified for a cruise missile strike during the Clinton administration. In his memoir, former DCI George Tenet, wrote that in providing the intelligence that could justify attacking Bin Laden, “My job was to assess objectively whether the data we had, often only from a single source, could ever get policy makers above a 50 to 60 percent.”

Decisionmaking

Keeping with the Obama administration’s preference for an orderly and thorough decisionmaking process, at least five Principals Committee meetings of the National Security Council were convened to review the intelligence and three proposed military options—a joint U.S.-Pakistani raid, a massive B-2 bombing strike, or a unilateral U.S. special operations raid. President Obama never considered alerting the Pakistanis to the intelligence beforehand, and rejected the B-2 strike because it would not have provided DNA proof that Bin Laden was dead, but was estimated to potentially have killed up to a dozen civilians. The concern of civilian casualties is a dubious explanation for Obama’s decision not to select the B-2 strike. In January 2006, President Bush authorized an attack by multiple Predator drones against a compound in the Pakistani village of Damadola, where it was believed Al Qaeda’s number two official, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was staying. The strikes reportedly killed eighteen civilians, including women and children, and four Al Qaeda militants, but al-Zawahiri survived. That civilians would be killed in attempting to eliminate a senior Al Qaeda official was not a deterrent to President Bush, and it is unlikely that it would have deterred President Obama had he determined a B-2 strike it was the best means to get Bin Laden.

President Obama said in a 60 Minutes interview, that despite all of the intelligence collection and analysis efforts, “at the end of the day, this was still a 55/45 situation. I mean, we could not say definitively that bin Laden was there.” rather than trying to obtain confirming information of Bin Laden’s presence at the Abbotabad compound, Obama authorized the operation to proceed. Why did Obama make this choice? One reason was that several hundred U.S. government employees had been briefed about the intelligence, and Obama was worried it could leak. Another possible explanation was that on April 25, Wikileaks published a September 2008 15-page secret memo that described information provided by the suspected terrorist, al-Libbi. This detailed memo specifically mentioned “UBL’s designated courier, Maulawi Abd al-Khaliq Jan,” and that al-Libbi had lived in Abbotabad with his family in 2003 to 2004. If the compound had internet access—it did not—Bin Laden could have had a better understanding of how much United States knew about the human network that kept him alive.

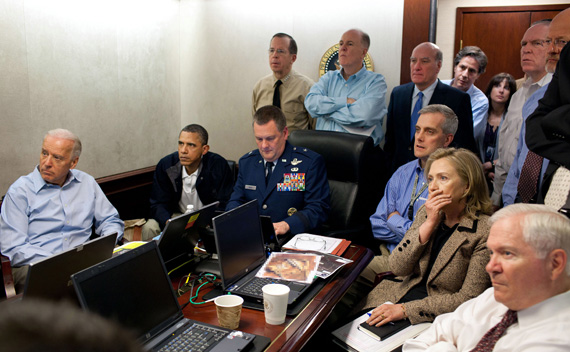

Many cabinet members have rightly praised President Obama’s decision as bold and gutsy, given that it could have resulted in U.S. casualties or permanently ruptured U.S.-Pakistani relations if the operation had gone wrong. Gates described it as “one of the most courageous calls, decisions that I think I’ve ever seen a president make.” James Clapper, the Director of National Intelligence, dubbed it “perhaps the most courageous decision I’ve witnessed in almost forty-eight years in intelligence.”

Nevertheless, historically presidents have not sustained major political damage from limited military operations that fail, including: the May 1975 bungled assault and bombing raids against Koh Tang, Cambodia, over the Mayaguez incident; Desert One, the April 1980, unsuccessful hostage rescue operation in Iran; the December 1983 raid on Syrian anti-aircraft sites in Lebanon that resulted in downed planes, one U.S. pilot killed, and another taken hostage; and Operation Infinite Reach, the August 1998 cruise missile strikes against an Al Qaeda training complex in Afghanistan that failed to kill Bin Laden. If the May 2 raid failed to kill Bin Laden, or worsened relations with Pakistan, it is unlikely that political or military leaders would have condemned the White House for making the effort.

Execution

Neptune Spear was a covert operation, defined in U.S. law (Title 50, section 413(e)) as “an activity or activities of the United States Government to influence political, economic, or military conditions abroad, where it is intended that the role of the United States Government will not be apparent or acknowledged publicly.” For the purposes of command and control, Leon Panetta was, as he described, “the person who then commands the mission” while Vice Adm. William McRaven, the Commander of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) “was actually in charge of the military operation that went in and got bin Laden.”

Once he was assigned as chief of the military operation, according to the Wall Street Journal, “McRaven assembled a team drawing from Red Squadron, one of four that make up SEAL Team 6. Red Squadron was coming home from Afghanistan and could be redirected with little notice inside the military.” On March 29, Adm. McRaven told President Obama that he needed additional time for the units to do dress rehearsals of the raid. Reportedly, an exact replica of the compound was built within the United States, and the SEALs executed practice runs on April 7 and April 13.

Nineteen days later, twenty-three Navy SEALS, an interpreter, and a tracking dog were airlifted into the compound on two Blackhawk helicopters, with additional troops in Chinook helicopters nearby in case they encountered Pakistani resistance and had to fight their way back into Afghanistan. It is unclear why the Pakistani military never detected the penetration of its airspace until one of the Blackhawks crash landed. (According to one report, Gen. Kayani’s first thought when informed of the helicopter crash was that Pakistan’s nuclear weapons were under attack.) Assuredly, the special operations pilots were well-trained in low-flying, radar-evading maneuvers. In addition, the Blackhawk helicopters were reportedly modified with extra blades to the main and tail rotors to make them quieter, and an infrared suppression coating to make them less observable by radars. Finally, in a May 13 closed-door session before the Pakistani Parliament, the country’s military chiefs revealed that radars intended to detect low flying objects were stationed on Pakistan’s eastern border with India, but not the northern border with Afghanistan.

It was also reported that the Pakistani Air Force immediately scrambled F-16s to the region, only to find that the Blackhawks had already re-entered Afghani airspace. Reportedly, the United States knew exactly how long it would take for those planes to get there, since the F-16s are stationed at an airbase with around-the-clock U.S. security surveillance. Even had they reached the exfiltrating helicopters in time, it is uncertain how they would have performed. A February 2008 diplomatic cable, obtained by Wikileaks, described how ineffective Pakistani F-16s were in night-time attacks in South Waziristan, “The use of the F-16s was presumably largely a show of force as the aircraft can only be employed during the day, while the attacks were at night.” Regardless, once Pakistan’s political and military leaders knew what had happened, Bin Laden had been killed and taken into U.S. custody.