A U.S. Air Force surveillance flight over Cuba in October 1962 turned up evidence of what U.S. officials had feared: the Soviet Union was installing nuclear-armed missiles on the island. The discovery triggered a thirteen-day crisis that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. President John F. Kennedy initially favored air strikes to take out the missile sites before they became operational. As a first step, he ordered a naval quarantine, or blockade, of Cuba. But worried about escalation to the unthinkable, he pursued backchannel communications with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev that ended the crisis. Alarmed by how close they had come to nuclear Armageddon, Kennedy and Khrushchev subsequently negotiated several agreements that lowered tensions between their two capitals and opened the door to the arms-control era. SHAFR historians ranked JFK’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis as the tenth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

The 10 Best U.S. Foreign Policy Decisions Ever

From securing America’s sovereignty to expanding its continental reach to creating the post-World War II institutions that ushered in unprecedented peace and prosperity, discover which U.S. foreign policy decisions left the most positive legacies.

Best Decisions

- 10

- 9

- 8

- 7

- 6

- 5

- 4

- 3

- 2

- 1

List of 10 Best Policy Decisions

-

The start of #10

#10 Best

Handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis

A U-2 plane used during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Courtesy of the Dino A. Brugioni Collection at The National Security Archive.

-

The start of #9

#9 Best

Monroe Doctrine

A political cartoon touting the Monroe Doctrine. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On December 2, 1823, President James Monroe delivered in writing his seventh annual address to Congress—the equivalent of today’s State of the Union address. In the middle of an otherwise forgettable summary of national issues, Monroe presented what would become a classic statement of U.S. foreign policy—the Monroe Doctrine. Monroe asserted that the Western Hemisphere was off limits to further European colonization and claimed the right for the United States to protect the sovereignty of the independent republics in the Western Hemisphere. Both claims were bold statements that the country had no way of backing up. But these bluffs were based on a shrewd diplomatic analysis that signaled to the world the far-reaching ambitions of the young country. SHAFR historians ranked the Monroe Doctrine as the ninth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #8

#8 Best

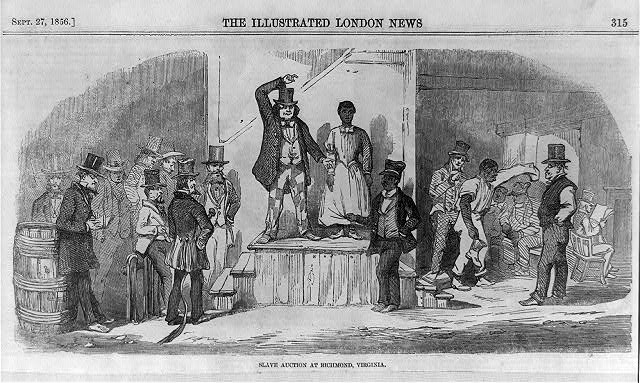

Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves

An enslaved women being auctioned in Richmond, Virginia, 1856. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The question of slavery’s future figured prominently when the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. Some delegates from Northern states hoped to banish the practice. They ultimately abandoned their fight in the face of the reality that the Southern states would rather bolt the convention, thereby dooming the effort to create a more effective national government, than agree to abolish slavery. The opponents of slavery, however, won one concession. The Constitution provided that after a twenty-year wait, Congress could ban the importation of enslaved people. In March 1807, at President Thomas Jefferson’s request, Congress did just that. On January 1, 1808, the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves went into effect. It was the first U.S. law that broke with the transatlantic slave system, and it curtailed U.S. participation in the international slave trade. SHAFR historians ranked the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves as the eighth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #7

#7 Best

Creation of the Bretton Woods System

Mount Washington hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Courtesy of the Library of Congress/Carol M. Highsmith.

As the United States fought World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was looking to lay the foundation for the world that would follow the fighting. He believed that the war had started in part because countries had pursued wrong-headed trade and monetary policies in the 1930s that intensified the Great Depression and fueled nationalism. FDR also knew that American firms and farmers would want to export to foreign markets once the war ended. Intent on correcting the mistakes of the past and hoping to spur future prosperity, Roosevelt convened a meeting of forty-four countries in July 1944 in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. For three weeks, the delegates to the conference—known formally as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference—hammered out the rules for a new international monetary system. At its heart lay two new multilateral institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (most commonly known as the World Bank), which became the pillars of the postwar global economic order. SHAFR historians ranked the creation of the Bretton Woods System as the seventh-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #6

#6 Best

Creation of NATO

President Harry S. Truman signs the North Atlantic Treaty proclamation. Courtesy of the Harry S. Truman Library & Museum/National Park Service/Abbie Rowe.

For much of its history, the United States shunned what Thomas Jefferson in his first inaugural address called “entangling alliances” with other countries. This meant, above all, standing apart from the political affairs of Europe. The United States broke with that tradition when it entered World War I, though President Woodrow Wilson insisted that the United States fought beside France and Great Britain as an “associated power” and not an allied one. After the war ended, the United States again turned its back on Europe. That pattern looked set to repeat when Germany surrendered at the end of World War II. However, Soviet efforts to dominate Europe changed U.S. calculations. Rather than returning home, the United States committed itself to the defense of Europe with the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). It became the most successful military alliance in history, deterring the Soviet Union and ushering in what has been called the “Long Peace” in Europe. SHAFR historians ranked the creation of NATO as the sixth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #5

#5 Best

Lend-Lease Act

Members of the English Auxiliary Territorial Service with boxes of rifles provided by the United States under the Lend-Lease Act. Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

In December 1940, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt with chilling news: Britain was on the verge of bankruptcy. The war with Germany, which had begun in earnest in the spring of 1940, had drained the British treasury. London would soon be unable to pay for the supplies and weapons it was buying from the United States. That might doom Britain’s effort to hold off the Nazi onslaught. Churchill’s news put FDR in a bind. A month earlier, he had won an unprecedented third term as president after promising Americans worried about the conflict in Europe that their “boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” But FDR also believed that a German victory would be disastrous for the United States. Knowing he had to act, he used the next three months to build congressional and public support for a plan to lend supplies to Britain and other countries fighting the Axis powers. The resulting Lend-Lease Act, which Churchill called “the most unsordid act,” provided more than $50 billion in aid to fifty nations and helped win World War II. SHAFR historians ranked the Lend-Lease Act as the fifth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #4

#4 Best

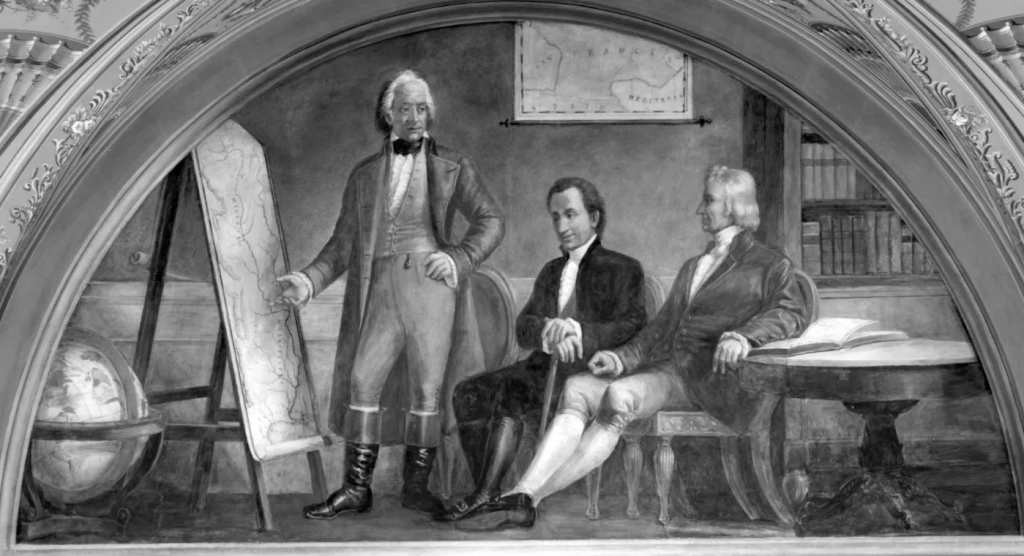

Louisiana Purchase

“Cession of Louisiana” by Constantino Brumidi, depicting the signing of the Louisiana Purchase, 1875. Courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol.

The United States emerged from the Revolutionary War with its independence, but the young nation remained vulnerable to foreign powers. Both France and Spain claimed territory west of the original thirteen states. Much of the trade of what was then the western United States flowed down the Mississippi River. First Spain and then France controlled the port of New Orleans, posing the threat that either could cripple the U.S. economy by cutting off access to the sea. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson sent envoys to Paris with instructions to pay up to $10 million to acquire New Orleans and as much of the territory east of the city as possible. However, French leader Napoleon Bonaparte made the Americans a surprise offer: he would sell the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million. Jefferson worried that nothing in the Constitution authorized such an acquisition. However, he swallowed his objections and jumped at the deal. The purchase more than doubled the size of the United States, secured control of the Mississippi River, and put the country on the path to becoming a continental power. SHAFR historians ranked the Louisiana Purchase as the fourth-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #3

#3 Best

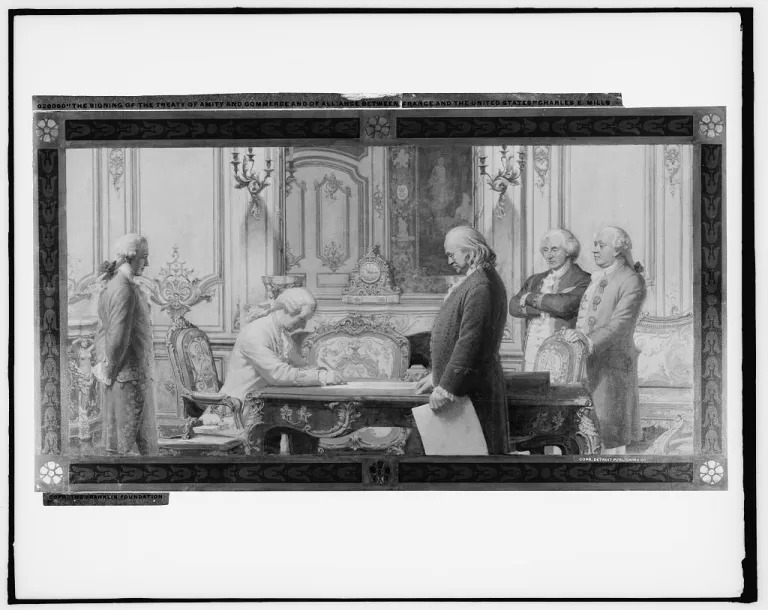

Treaty of Alliance With France

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

When the thirteen colonies declared independence in 1776, they turned to Great Britain’s rival France for aid. At first, France provided only clandestine support. It feared that publicly siding with rebels who were likely to lose would risk a war with Great Britain that had few benefits. But adept U.S. diplomacy and a critical American battlefield victory changed that calculation. On February 6, 1778, France recognized the independence of the thirteen American colonies and pledged to support their war with Great Britain. The agreement, which was codified in two separate treaties, was a turning point in the American Revolutionary War. France subsequently provided the colonies not only with military supplies and financial support, but also with land and naval forces. France’s entry into the war also forced Great Britain to divide its forces to guard against threats to its interests in Europe and the Caribbean as well as in the thirteen colonies. A war that the colonists seemed destined to lose became a war that they won—and that changed the course of history. SHAFR historians ranked the Treaty of Alliance with France as the third-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #2

#2 Best

Creation of the United Nations

UNGA_picture

On October 24, 1945, the Charter of the United Nations came into force, establishing the United Nation’s structure, principles, and purpose. The new organization was the culmination of a yearslong effort led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had died six months earlier. The objective had been to address the failures of the League of Nations, which was created after World War I, by developing a new international institution that could formalize common efforts to maintain global peace and security, develop friendly international relations, and tackle economic, social, cultural, humanitarian, and public health problems worldwide. Although the United Nations has fallen short of fulfilling Roosevelt’s lofty goals, its role as a forum of international debate, its many peacekeeping operations, and its wide-ranging humanitarian activities nonetheless mark its founding as a major triumph for the United States. SHAFR historians ranked the creation of the United Nations as the second-best U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #1

#1 Best

Marshall Plan

Library of Congress

On April 3, 1948, President Harry Truman signed into law the Economic Cooperation Act of 1948, better known as the Marshall Plan. Named after its main proponent, Secretary of State George C. Marshall, the law authorized one of the largest foreign aid programs in history. From 1948 to 1951, the United States provided sixteen countries in Western Europe $13.2 billion in assistance—equivalent to roughly $180 billion today—to buy food and goods and to invest in their infrastructure and industry. The Marshall Plan revitalized postwar Europe, blunted Soviet influence in Western Europe, encouraged intra-European cooperation, and cemented the United States’ leadership of the transatlantic alliance. SHAFR Historians ranked the Marshall Plan as the best U.S. foreign-policy decision.

The 10 Worst U.S. Foreign Policy Decisions Ever

From violent westward expansion to interwar isolationism to ruinous military interventions, discover which U.S. foreign policy decisions left the most tarnished legacies.

Worst Decisions

- 10

- 9

- 8

- 7

- 6

- 5

- 4

- 3

- 2

- 1

List of 10 Worst Policy Decisions

-

The start of #10

#10 Worst

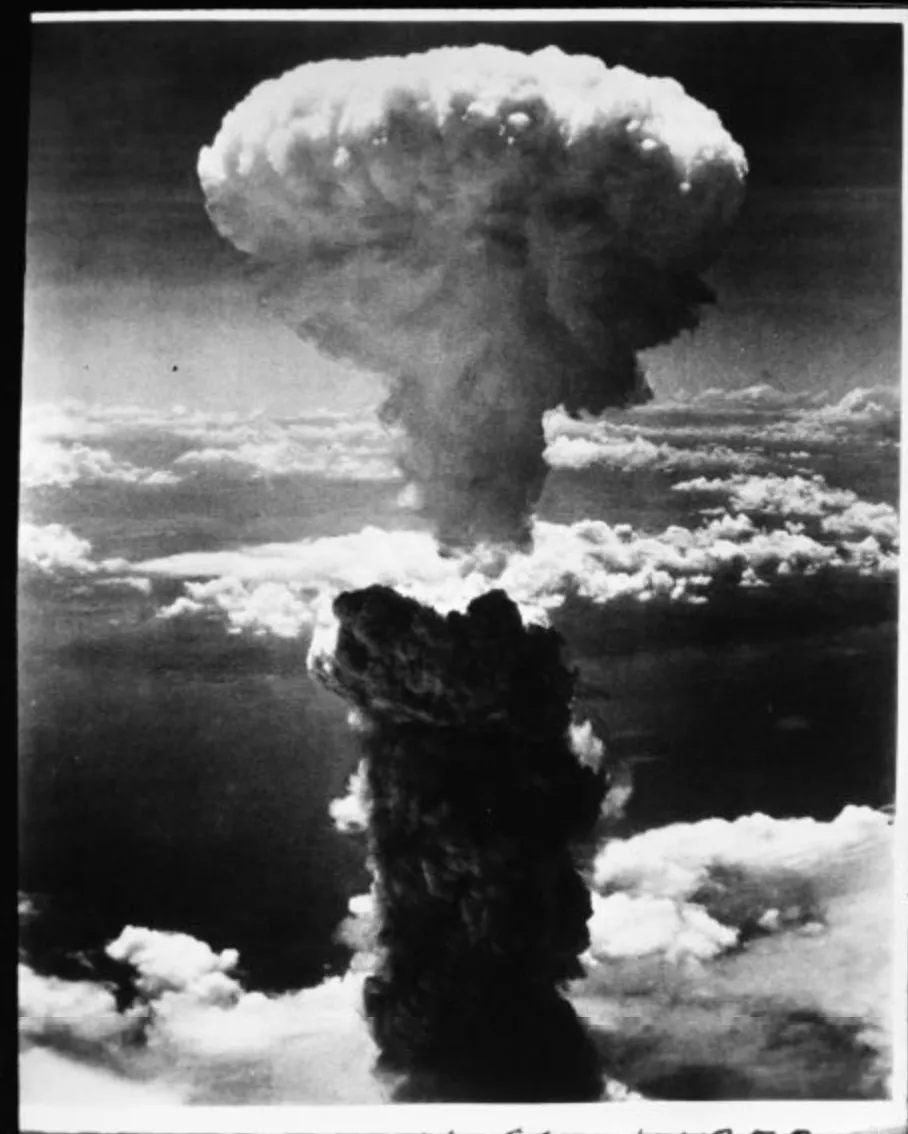

Bombing of Nagasaki

Smoke rises over Nagasaki after the atomic bombing, August 9, 1945. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration/United States Army Air Forces.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. That first-ever use of an atomic weapon killed an estimated 140,000 people in all, most of whom were civilians. Three days later, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Some 40,000 people, again mostly civilians, died instantly. Another 34,000 died agonizing deaths in the weeks that followed. President Harry S. Truman argued that the bombings were necessary to compel Japan’s surrender and to avoid what likely would have been a far deadlier U.S. invasion. Truman’s decisions, and particularly the decision to bomb Nagasaki, remain hotly debated. The attacks subjected civilian populations to horrific devastation with long-lasting effects. The bombing of Nagasaki was launched two days earlier than planned to avoid bad weather, leaving the Japanese government less time to assess what had happened to Hiroshima and possibly quit fighting. Truman’s private comments suggest that his decision to bomb Nagasaki went beyond forcing Japan’s surrender to include intimidating the Soviet Union. SHAFR historians ranked the bombing of Nagasaki as the tenth-worst decision in U.S. foreign policy history.

-

The start of #9

#9 Worst

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

The USS Maddox at sea. Courtesy of the United States Naval History and Heritage Command.

On August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese patrol boats attacked the USS Maddox, a destroyer operating in international waters in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam. Two nights later, the Maddox reported that it had come under fire again. President Lyndon B. Johnson responded to the news by ordering airstrikes on North Vietnam—the first overt U.S. attack on the country. Johnson also asked Congress to endorse his decision to confront North Vietnamese aggression. Congress complied in less than seventy-two hours by passing the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. What members of Congress did not know was that much of what the Johnson administration told them about why the Maddox was in the Gulf of Tonkin was untrue and that the second attack likely never occurred. Acting in haste and with bad information, Congress approved deepening U.S. involvement in what would become the Vietnam War. SHAFR historians ranked the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution as the ninth-worst U.S. foreign-policy decision.

-

The start of #8

#8 Worst

Limits on Jewish Refugees From Germany

Jewish refugees aboard the MS St. Louis, June 3, 1939. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Nazi Germany’s persecution of so-called non-Aryans in the 1930s pushed Jews, first in Germany and then in the countries that Germany seized, to seek refuge elsewhere. Many refugees hoped to find safety in the United States. Yet even as Nazi control over Europe expanded, the United States strictly limited immigration. The refusal to address the growing humanitarian crisis reflected antisemitism, nativism, bureaucratic red tape, and unfounded fears that refugees would become a burden on the government or work as German spies. The United States stuck to its restrictive immigration policy even though President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other leading U.S. officials condemned Germany’s treatment of Jews, and U.S. newspapers frequently covered the plight of refugees. The U.S. refusal to admit more refugees meant that tens of thousands of people who might have been saved instead perished in the Holocaust. SHAFR historians ranked the U.S. insistence on limiting the number of Jewish refugees in the years before World War II as the eighth-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #7

#7 Worst

Withdrawal From the Paris Agreement

World leaders at the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris, November 30, 2015. Courtesy of UN Photo.

The signing of the Paris Agreement in December 2015 marked a breakthrough in climate diplomacy. After numerous prior failed attempts, 194 countries agreed to work to reduce the emission of heat-trapping gases like carbon dioxide and methane that are changing the climate. The United States, the world’s second largest emitter annually and the largest emitter cumulatively, was among the countries that signed the Paris Agreement, which is also known as the Paris climate accord. On June 1, 2017, President Donald Trump, who had come to office five months earlier, fulfilled a campaign promise by announcing that the United States would withdraw from the Paris Agreement. He argued that the agreement would hamstring the U.S. energy industry and cost millions of American jobs while doing little to limit climate change, something he had repeatedly called a “hoax.” No other country followed Trump’s lead, leaving the United States diplomatically isolated as average global temperatures climbed and extreme weather events multiplied. SHAFR historians ranked the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement as the seventh-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #6

#6 Worst

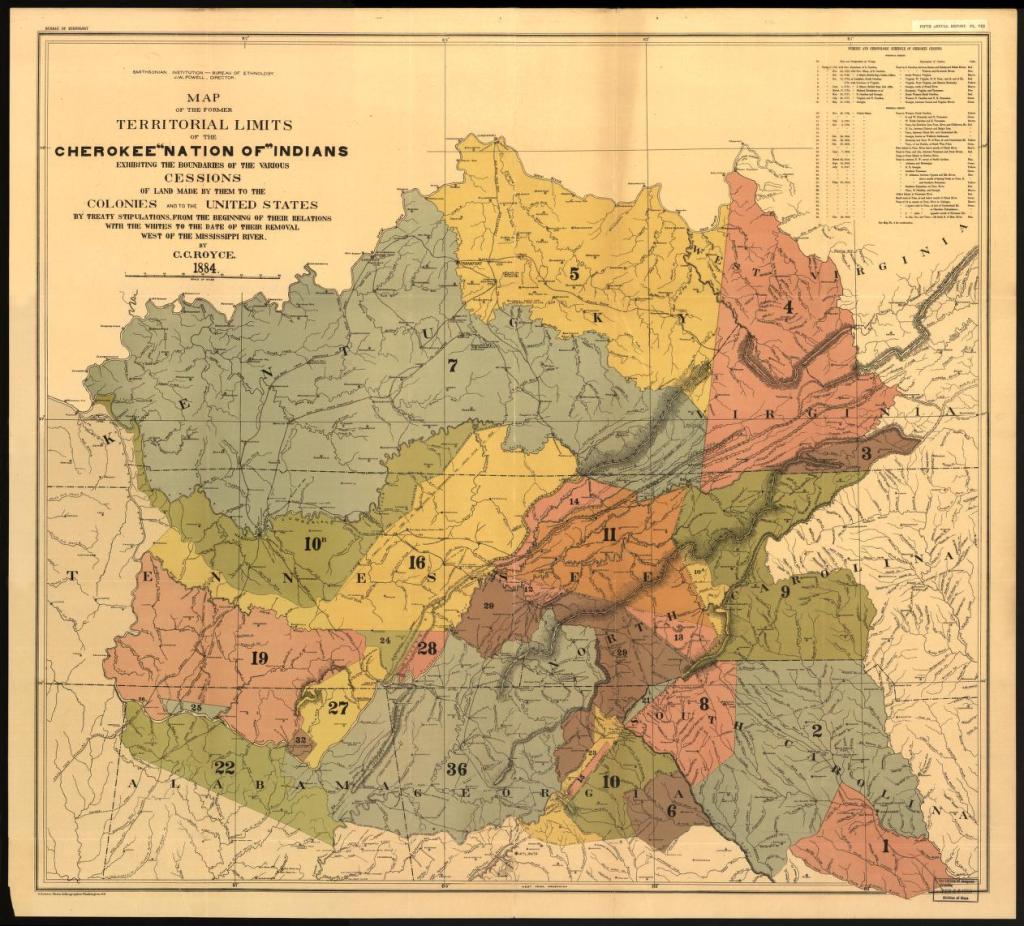

Forcible Removal of the Cherokee Nation

Map showing territory allocated to Cherokee Nation, 1884. Courtesy of the Library of Congress/C.C. Royce.

In the early nineteenth century, white settlers in the eastern United States increasingly encroached upon the lands of Native Americans. Although the U.S. government had signed treaties demarcating native territory, political pressure grew to disregard them. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to grant lands west of the Mississippi River to Native American tribes that gave up their lands east of the river. In 1832, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans constituted “separate nations” who were not subject to state law. President Andrew Jackson ignored the ruling. On May 23, 1838, the first members of the Cherokee Nation were pushed out of their lands in what is now the southeastern United States and forced to walk to their new territory in northeastern Oklahoma. Four thousand of the sixteen thousand Cherokee who began the journey died on what became known as the Trail of Tears. SHAFR historians ranked the forcible removal of the Cherokee Nation as the sixth-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #5

#5 Worst

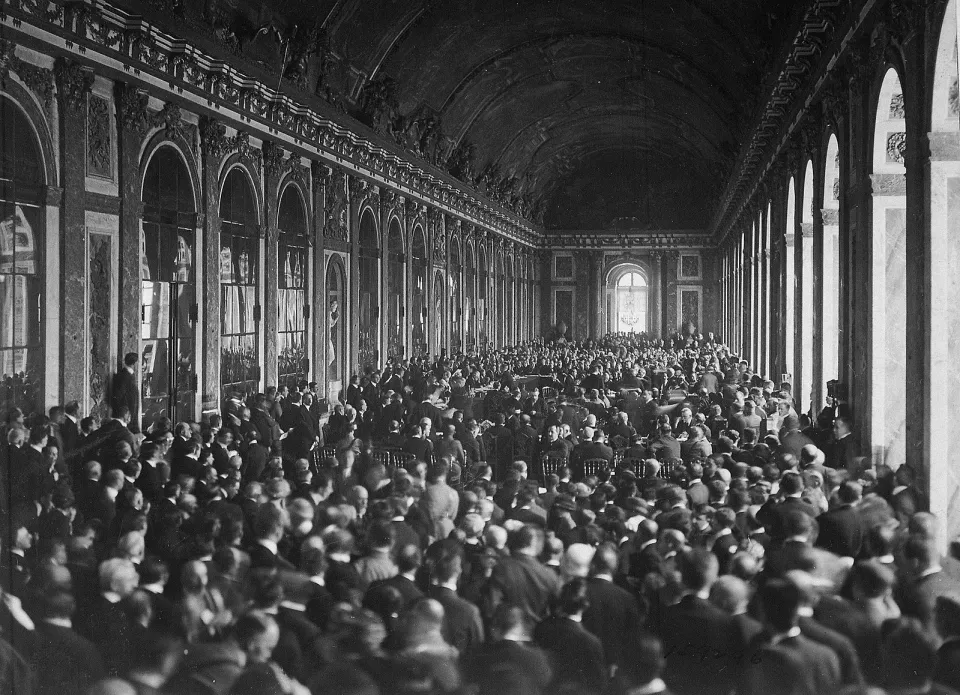

Senate Rejection of the Treaty of Versailles

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles at the Galerie des Glaces, June 28, 1919. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The U.S. entry into World War I broke with the United States’ longstanding practice of keeping out of Europe’s political affairs. President Woodrow Wilson saw that shift as an opportunity to try to restructure world politics to make future conflict less likely. He went to Paris in December 1918 to negotiate the war’s end. There he negotiated the Treaty of Versailles, which embraced his vision to create a League of Nations that would work to preserve peace. Wilson did not have similar success, however, at home. In November 1919 and again in March 1920, the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, and with it, the League of Nations. The league began operating in 1920, but the absence of the United States handicapped its work. Declining to join the league also made it easier for the United States to ignore growing world crises over the next two decades, a decision it would come to regret. SHAFR historians ranked the Senate rejection of the Treaty of Versailles as the fifth-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #4

#4 Worst

Support for the Overthrow of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq

Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq in Washington, DC, 1951. Courtesy of Harry S. Truman Library & Museum/Department of State.

Mohammad Mosaddeq became prime minister of Iran in April 1951. An ardent nationalist, he rose to power by challenging Great Britain’s dominance of Iran’s economy and politics. A month before becoming prime minister, Mosaddeq led the effort by the Iranian Majlis (parliament) to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), which the British government controlled. Rather than seek compromise with Tehran, London sought to reverse the law by crippling Iran’s oil exports, the main source of government revenue. President Harry S. Truman rejected British efforts to enlist the United States in pressuring Iran to return ownership of AIOC to Britain. British arguments that Mosaddeq was destabilizing Iran found a more friendly audience when Dwight D. Eisenhower became president. Fearing that a communist takeover of Iran was increasingly likely, Eisenhower authorized Operation Ajax to oust Mosaddeq. The coup came in August 1953. Its success encouraged subsequent U.S. efforts to destabilize governments Washington disliked, and Iranian nationalists used the coup to fuel anti-Americanism in Iran. SHAFR historians ranked the support for Mosaddeq’s overthrow as fourth-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #3

#3 Worst

Indian Removal Act

George Winter’s depiction of the forced removal of the Potawatomi tribe, 1837. Courtesy of Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center.

White settlers in the United States in the early nineteenth century coveted the land held by Native Americans. The U.S. government initially sought to limit the resulting conflict by treating Native American tribes as sovereign nations and negotiating treaties that established the boundaries of their lands. The U.S. government generally did little, however, to force settlers to respect the terms of treaties. Instead, Washington frequently imposed new treaties on Native Americans with even less favorable terms. With tensions between the two communities increasing, enthusiasm grew in the United States for expelling Native Americans from their ancestral lands. In 1830, Congress passed, at President Andrew Jackson’s request, the Indian Removal Act. Over the next two decades, the U.S. government repudiated its solemn treaty obligations and forced as many as one hundred thousand Native Americans living east of the Mississippi to relocate to smaller lands west of the Mississippi. SHAFR historians ranked the Indian Removal Act as the third-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #2

#2 Worst

Deployment of Combat Forces to Vietnam

U.S. Marines arrive at Da Nang, South Vietnam, March 8, 1965. Courtesy of the United States Marine Corps.

On March 8, 1965, 3,500 Marines from the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade arrived in Da Nang, South Vietnam. Their mission was to protect a U.S. air base from attacks by the self-proclaimed National Liberation Front (NLF), the guerrilla force seeking to overthrow the South Vietnamese government that was better known to Americans by the pejorative name Viet Cong. Six days earlier, the United States had begun Operation Rolling Thunder, a bombing campaign against North Vietnam that would last for three years. Some U.S. officials opposed sending the Marines to Da Nang, predicting that President Lyndon B. Johnson would soon be pressed to send even more troops into a war that could not be easily won. Despite his own deep misgivings about the ability of the United States to win a conflict he called “the worst mess I ever saw in my life,” Johnson committed another 120,000 troops to South Vietnam over the next 5 months and more than a half million over the next three years. The war, however, remained unwinnable. SHAFR historians ranked the deployment of U.S. combat troops to Vietnam as the second-worst U.S. foreign policy decision.

-

The start of #1

#1 Worst

The Invasion of Iraq

U.S. soldiers in Sāmarrāʾ, Iraq, 2004. Courtesy of The United States Department of Defense/Johan Charles Van Boers

The September 11, 2001, attacks heightened fears in the United States that Iraq might give terrorists weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Although the United Nations had pressed Iraq to dismantle its nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons programs after the 1991 Gulf War, President George W. Bush argued that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein had continued to pursue them. The UN Security Council threatened Iraq with “serious consequences” in late 2002 if it failed to cooperate with weapons inspections, but it declined to authorize an invasion. The United States responded by organizing a “coalition of the willing” to oust Hussein. Operation Iraqi Freedom began on March 20, 2003, and quickly overran Iraqi forces. However, no evidence of any active Iraqi WMD programs was found. The United States became embroiled in a bloody war of occupation that lasted eight years and cost it dearly, damaging its global reputation and empowering anti-American forces throughout the Middle East and worldwide. SHAFR historians ranked the invasion of Iraq as the worst U.S. foreign policy decision.