Trump’s Japanese and EU Investment Boasts Contradict His Claims of a Trade Deficit “Emergency”

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

The Trump administration’s recent trade deals with Japan and the EU raise tariffs on the two large trade partners dramatically, relative to their pre-April levels. Although levying tariffs is a Constitutional prerogative of Congress, the administration has asserted its levying powers under the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), claiming that the long-standing U.S. current account deficit represents a “national emergency.”

As part of those trade deals, Japan has, according to Trump, over the coming three and a half years committed to $550 billion of new inward investment into the United States, and the EU has committed to $600 billion. Details are sorely lacking, and statements from Tokyo and Brussels have considerably downplayed the size and degree of “commitment” involved. But it is significant that Trump considers such investment pledges a victory for his trade policy, given that his boasts contradict his claim of a “national emergency” in trade.

Broadly speaking, the dollars flowing into this country must come from selling us more goods and services—or from buying less from us. In balance-of-payments terminology, inward investment into the U.S. increases the U.S. capital account surplus, but, as an accounting identity, also increases the current account deficit. By the president’s own logic, therefore, his Japan and EU deals worsen the “national emergency” that he identified to claim the power to levy tariffs. As a matter of both economics and legality, then, this is a serious error of reasoning.

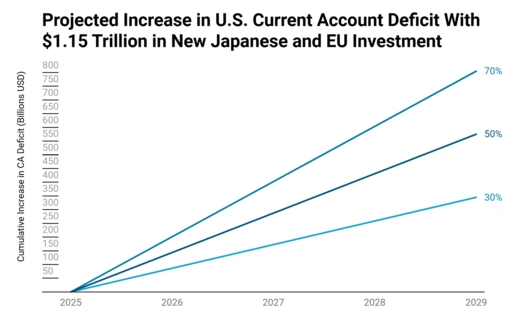

To see how significant the error is, consider the likely impact of $1.15 trillion in new, unanticipated inward investment between now and the end of 2028. An increase in the capital account surplus must be matched by an increase in the current account deficit of the same magnitude. In practice, however, only part of the inflow tends to show up in the current account over a short window like 3.5 years. Very roughly, empirical research suggests that 30-70 percent of large capital inflows show up in the current account over 3-5 years, depending on the type of inflows (FDI, portfolio, or bank loans) and macroeconomic conditions. If we assume, then, that half of the inflows translate into a wider current account deficit over 3.5 years, then $1.15 trillion in new inward investment from Japan and the EU would add a cumulative $575 billion to the current account deficit—or $165 billion per year. The graphic above shows the progression of that cumulative increase going forward under the assumptions of 30 percent, 50 percent, and 70 percent pass-through.

Whether inward investment on the scale claimed by the president is, on net, desirable or undesirable is debatable, given the complexities involved in macroeconomic cause-and-effect. But it is undeniable that the president is on the weakest possible logical ground in wanting both massive new inward investment and an elimination of the trade deficit.