China’s Currency is Now Facing Substantial Appreciation Pressure

China wants a slow, managed move in its currency. The market—and China’s trading partners—may not be as patient.

The conventional wisdom among China watchers has long been that China will not allow a substantial appreciation of the yuan because its still hobbled domestic economy needs the boost from exports. George Magnus wrote on the site formerly known as Twitter:

“[China’s post-Covid export boom] is not so much a source of pride or success, as reflection of weak domestic demand, and Beijing’s inability or unwillingness to address it...”

And as a result, “while the USD [exchange] rate [of the RMB] has risen a bit, the RMB remains structurally weak. And will [remain so]”

After all, net exports have delivered something like a third of China’s reported growth in each of the last two years, and perhaps more, as many suspect the other components of China’s growth are over-stated.

The conventional wisdom among many trade watchers is that China cannot continue to generate so much growth from exports, because if it did, the global trading system—already under immense strain because of Trump—will break. French President Macron spoke for many when he warned “these [trade] imbalances are becoming unbearable.”

The U.S. Treasury, which has been rather sleepy on currency issues under Secretary Bessent, is likely to wake up at some stage.*

An immovable object—China’s commitment to the basic stability of yuan—is meeting a potentially unstoppable political force, and testing limits of China’s trading partners’ willingness to absorb China’s ever-increasing export surplus.**

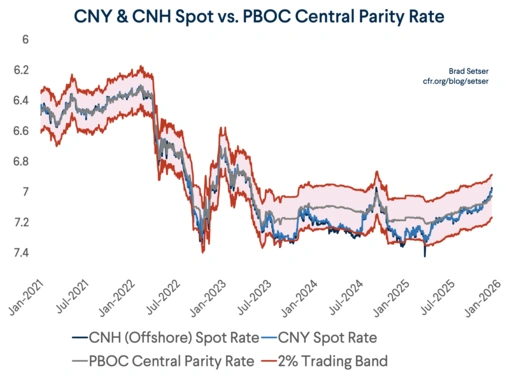

After all, if China limits nominal appreciation to a few percentage points (to match, say, the rate differential between the yuan and the dollar in an effort to limit speculative pressure) China’s real exchange rate won’t move, and if the real effective yuan stays at its current depreciated level, China is likely to continue to gain global market share.

But China’s exchange rate is no longer being ignored by either the IMF or the foreign exchange market, and that is a bit of a change. The fact that the yuan is significantly undervalued—and that undervaluation has contributed to China’s export out-performance—is now generally accepted (see IMF managing director Georgieva’s comments at the conclusion of the IMF mission). That was not the case a year ago (go back and reread the IMF’s 2024 staff report on China; it stands as an embodiment of the conventional wisdom of the time).

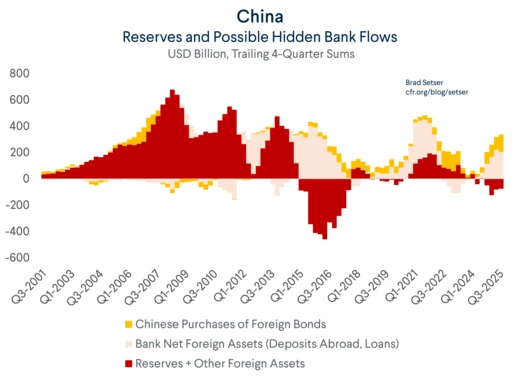

There is now a broad consensus that China’s trade surplus is a real concern (and a growing consensus; see Dr. Krugman’s Substack) that the true size of China’s surplus cannot just be read from the reported current account surplus (it is on track to reach close to $700 billion in 2025, which isn’t small, but the true surplus is likely already close to $1 trillion).

Finally, there is also a growing recognition that the yuan is now under pressure to appreciate. Goldman’s call for a major yuan appreciation in 2025 both reflects that shift and contributed to it. Until recently, the conventional wisdom was that the yuan was under depreciation pressure. Some at the IMF supposedly still think that, despite the clear signal from the foreign exchange settlement data. But market views are evolving rapidly.

To be sure, that pressure is coming in the context of China’s still largely closed financial account—and the closed financial account traps Chinese savings inside China. But China’s is not going to suddenly open the floodgates and allow unfettered inflows and outflows, so it makes sense to assess the pressure that is coming from within the existing system.

That pressure is clearly for more appreciation.

The settlement data for the last several months has averaged around $30 billion a month in net FX purchases since June. There are a ton of signs that the December settlement number could be substantially larger than the October and November numbers, not the least persistent reports of state bank activity by Bloomberg.

As a result, China’s authorities are trying their best to signal that the yuan isn’t a one-way bet—and that investors shouldn’t pile into the yuan.

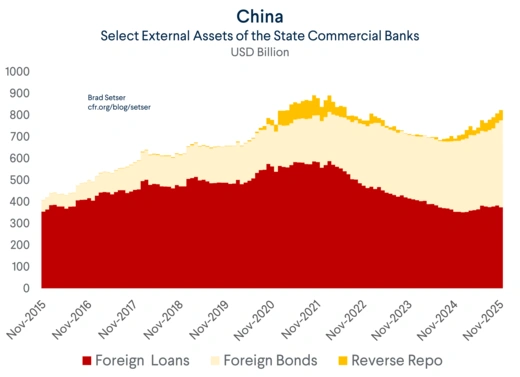

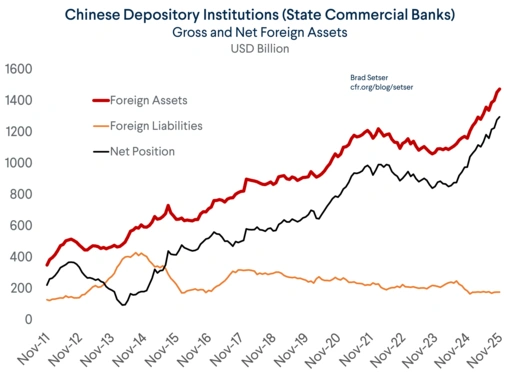

That gets at the core dilemma China faces now with its exchange rate management. For most of the past few years, rate differentials have favored the dollar. That, plus depreciation of the yuan against the dollar in 2022, China’s own extended downturn and tariff threats, combined to generate a sustained private outflow from China that offset the growing trade surplus. But over the last few quarters, private outflows have not matched the still expanding trade surplus, and as the yuan started to crawl up against the dollar, China’s state banks have resumed their accumulation of foreign assets.***

The pace of their foreign asset accumulation is large absolutely; $300 billion annually, maybe a bit more.

But it still isn’t that big relative to China’s economy. If state bank foreign asset accumulation was treated as a form of backdoor currency intervention, it would have remained just under the two percent of GDP threshold (now ~$400 billion) that the U.S. Treasury uses to assess “manipulation” in its currency report.

But keeping the scale of state bank accumulation modest is likely to be a growing challenge.

The underlying trade surplus is much bigger that the accumulation of foreign assets by the state banks in recent quarters, which indicates that there is room for pressure on the currency to increase if the direction of capital flows changes.

If it’s clear that the yuan will mostly likely be allowed to appreciate only slowly but there is a small change of a big move, well, it makes sense for Chinese exporters and currency traders alike to start betting on the yuan.

Historically I haven’t always agreed with Stephen Jen (he once believed that China and the U.S. were so tightly linked that they should be considered a de facto currency union, and the Chinese surplus should be added to the U.S. deficit to get the combined balance of a trans-Pacific dollar zone). But I do agree with Dr. Jen’s argument that there is a lot of latent demand for yuan from Chinese firms that hoarded dollars during the last five years. If there is a grinding and slow but predictable appreciation, some of those offshore dollars will come home, and that will add to the underlying appreciation pressure.

In other words, SAFE’s currency management is about to become interesting again.

Holding the yuan’s nominal appreciation to 2-3 percent (less than the rate differential between the dollar and the yuan) will help to limit speculative pressure, but it won’t correct the yuan’s real undervaluation, and the resulting expansion of China’s surplus will likely trigger a trade reaction from China’s trading partners at some stage.

Yet a faster pace of appreciation risks pulling in Chinese offshore money. As a result, keeping the appreciation controlled will require more, not less, intervention in the market.

These are many of the dilemmas that China has confronted in the path. There are answers, but they require making a few fundamental choices. I suspect that asserting old slogans and warning against one-way bets won’t cut it much longer.

* The Treasury’s foreign currency report has been delayed by the U.S. government shutdown last fall, and perhaps by a desire not to disrupt the “Busan” trade détente. Last Spring, the Treasury promised to update its methodology to more explicitly examine the activity of sovereign wealth funds, national pension funds, and state banks—so there is ample ground for calling out China’s backdoor intervention more forcefully.

** Export volume growth will average 9-10 percent in 2025, with import volume growth of only 0-1 percent (even with some strategic stockpiling). That follows double digit export volume growth in 2024 (taking the average of monthly changes). In the Dutch trade series, Chinese exports have outperformed global trade by a factor (2-3x) while imports have wildly underperformed. That is the definition of unsustainable.

*** The state banks’ foreign assets series leaves out the policy banks, and it technically includes yuan-denominated foreign assets, which have been increasing recently. But both the FX settlement data and the state commercial banks foreign currency balance sheet numbers show renewed accumulation of foreign currency assets as well.