Political Realignment and the 2026 Japanese Election II

This Sunday, Japanese voters will once again go to the polls. Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae has called this snap election in the hopes of attracting sufficient votes to put her party, the LDP, back in the majority.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Sheila A. SmithJohn E. Merow Senior Fellow for Asia-Pacific Studies

By Sheila A. SmithJohn E. Merow Senior Fellow for Asia-Pacific Studies

By

- Chris BaylorResearch Associate, Asia-Pacific Studies

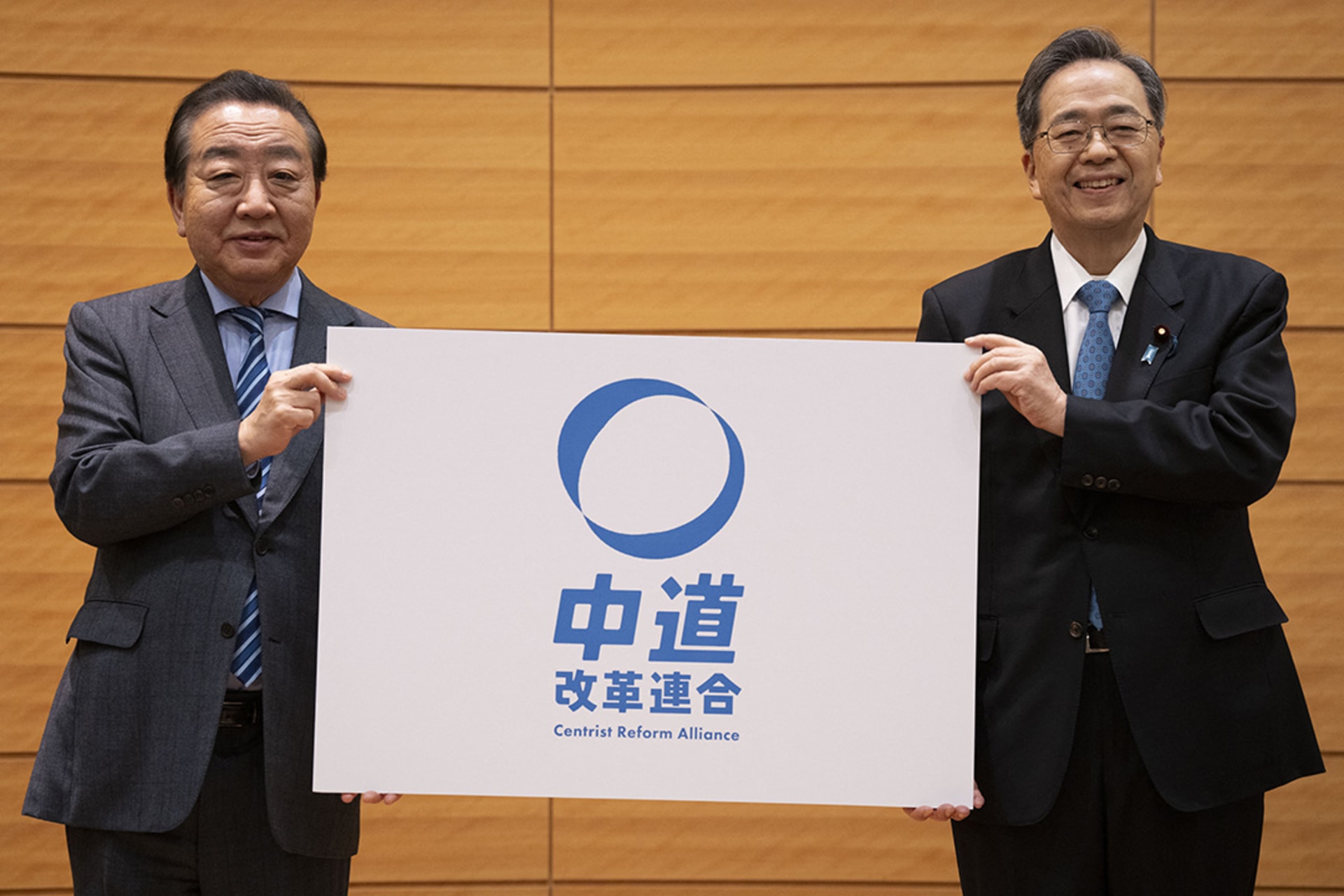

This Sunday, Japanese voters will once again go to the polls. Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae has called this snap election in the hopes of attracting sufficient votes to put her party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), back in the majority. Her new coalition partner, the Ishin no Kai, is also hoping to boost its standing. Polls suggest the prime minister’s election gamble may pay off, while the main opposition party, the newly formed Centrist Reform Alliance (CRA), seems to be struggling.

This realignment of parties has broader ramifications for governance. To be sure, Japanese voters are worried about affordability and the growing economic pressures on their households. But there are other longer term social issues informing political debate. Three, in particular, may offer insights into this election. The first was the concern over the growing number of non-Japanese in society. The second is the age-old frustration with money in politics, and the broader goal of political reform. And, the third is Japanese concerns over national security.

Political Reform

Two efforts at political reform are worth attention. The first is the demand for greater regulation of political fundraising. The LDP has long been susceptible to “money and politics” (seiji to kane) scandals, but legal restrictions have helped enhance transparency and accountability. The LDP too has instituted tighter rules over campaign funding. Former Prime Minister Kishida Fumio investigated reports of unreported slush funds, mostly sourced from fundraising parties, and many LDP members were found to have violated the Political Funds Control Act.

The LDP and the Slush Fund Scandal

In November 2023, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio asked Motegi Toshimitsu, Secretary General of the LDP, to investigate reports of the mishandling of campaign funds. The party’s Disciplinary Committee found that a number of prominent LDP members, many associated with the former Abe faction, were implicated in this slush fund scandal. Four cabinet ministers were forced to resign including Matsuno Hirokazu (Chief Cabinet Secretary), Nishimura Yasutoshi (Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry), Suzuki Junji ( Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications), and Miyashita Ichiro (Minister of Agriculture). In total, over eighty LDP Diet members incorrectly reported their political funds from 2018-2022.

After party deliberations, the LDP Disciplinary Committee announced thirty-nine Diet members were guilty of violating party rules. Two members were recommended for immediate expulsion from the party, three were suspended from the party for six months to one year, and seventeen were barred from holding any party positions for six months to one year. The remaining Diet members were given a reprimand.

This scandal had an immediate impact on LDP fundraising. Regular reporting on political donations and party fundraising is required under the Political Funds Control Act (政治資金規正法), and the 2024 report (政治資金収支報告書), released in November 2025, revealed a decline in LDP donations. According to the Yomiuri Shimbun, the LDP’s total earnings from political fundraising parties fell by 46.7 percent from 2023. The individual Diet members who reported the largest decrease in donations were the prime minister himself, Kishida Fumio (from ¥131 million to ¥50 million), former Olympics Minister Endo Toshiaki (from ¥90 million to ¥72 million) and Nishimura Yasutoshi (from ¥43 million to ¥8 million). Corporate donations to the LDP’s party fundraising organization ( 国民政治協会) also declined, dropping by 1.3 percent. Nonetheless, the LDP still attracted ¥2.39 billion (around $15.5 million) in donations from corporations, 10 percent of the party’s total fundraising.

Public distrust of the LDP’s management of campaign funds lingered, and the prime minister stepped down on October 1, 2024. Ishiba Shigeru was elected as the new LDP president and assumed responsibility for the follow-up of the party’s investigation. While Ishiba did not instigate major reforms, he did enforce additional disciplinary action. In two elections, the Lower House in 2024 and the Upper House in 2025, those found guilty of violating party rules were not endorsed by the LDP. Additionally, Ishiba decided that those implicated would not be allowed to have their names on the party’s proportional seat list.

Twelve implicated candidates had their party endorsement revoked in the 2024 Lower House election and were forced to run as independents. Only three were re-elected: Hagiuda Kōichi, Nishimura Yasutoshi and Hirasawa Katsuei. The thirty-four implicated members who were still LDP-endorsed struggled and only fourteen were re-elected. Even in the 2025 Upper House election, five of the fifteen implicated members who ran for office failed to be re-elected.

When Takaichi assumed leadership of the LDP in October 2025, the party declared this issue to be settled. In running to become party president, Takaichi took the position that those implicated had been punished, stating that, “disciplinary actions have been taken, and they have faced the judgment of the electorate.”1 If elected, she said she would allow those involved to play a full role in party affairs. Takaichi won and went on to do just that. She even appointed Hagiuda Kōichi to the influential party post of Acting Secretary General, a move that surprised many.

For this upcoming Lower House election, the LDP has re-endorsed seven candidates who had their endorsement revoked in the 2024 election and they will be included in the LDP proportional candidate list. Furthermore, the LDP’s election campaign manifesto includes two positions on political fundraising: first, the party will emphasize disclosure over prohibition and second, it will work with other parties to develop new legislation on campaign fundraising by September 2027. Recent electoral losses are widely seen as a rebuke of the LDP by Japanese voters. After the 2024 Lower House election, an Asahi Shimbun poll showed that 82 percent of their respondents believed that the slush-fund scandal was a major factor in the LDP’s loss. In addition, a Yomiuri Shimbun poll conducted after the 2025 Upper House election showed that 81 percent of their respondents thought that implicated LDP members bore the responsibility of the party’s loss.

Opposition Parties Align on Fundraising

Opposition parties had long identified the problem of money in politics, and the LDP has often been the target of their criticism. Business and other organizational donors have been the focus of recent calls for restrictions on campaign donations.

Many have called for outright bans or strengthening of regulations for corporate and political donations. The Democratic Party for the People (DPP) and CRA advocate for stronger restrictions and for a third-party monitor for political fundraising.

Ishin no Kai bans corporate and organizational donations to their party and calls for a full ban on these donations for all parties. But in coalition negotiations with the LDP, they softened their stance and agreed to a step-by-step approach to legislating fundraising reform.

The biggest casualty of the recent money and politics scandal was the LDP-Komeitō coalition. After she assumed the leadership of her party, Takaichi Sanae met with Komeitō leader Saitō Tetsuo to discuss electoral cooperation, but their talks faltered over restricting corporate donations. The LDP and Komeitō held three rounds of discussions, with Komeitō stipulating that the LDP must take concrete action to strengthen regulations on corporate and political donations. Takaichi pushed back, arguing they could consider stricter regulations in future, but on October 10, 2025, Saitō publicly announced that his party would not return to the coalition.

This ended twenty-six years of cooperation between this small, Buddhist-affiliated party and Japan’s conservatives. Their coalition had both electoral and policy impact. Komeitō was often referred to as the LDP’s junior partner. Indeed, it was far smaller in size, garnering around thirty seats in the Lower House over the years and around ten seats in the Upper House. Komeitō has held Cabinet positions, usually one, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. But cooperation with Komeitō allowed the LDP to form majority governments since 1999. Moreover, in single-member constituencies, analysts estimate that Komeitō could bring approximately twenty-six thousand voters to the polls, a remarkable boost to LDP candidates in both rural and urban districts. In terms of policy, the inclusion of Komeitō in the ruling coalition allowed for greater attention to social security support and tempered the government’s defense policy goals. Indeed, former Komeitō party president, Yamaguchi Natsuo repeatedly referred to his party’s role as the hadome, or brake, on the LDP’s push to normalize the Self-Defense Force, Japan’s postwar armed services.

Reduction of Legislative Seats

Another area of political reform is emerging on the national agenda, one that will largely affect smaller parties. As part of their coalition agreement with the LDP, the Ishin no Kai argued for reducing the number of seats in the Diet. Ishin has advocated for a reduction in the size of government, including this emphasis on reducing Japan’s bloated legislature and bureaucracy. Dubbed the Self-Defeating Reforms (身を切る改革), Ishin hopes to reduce government spending and create a nimbler approach to solve Japan’s new challenges. Ishin leader Yoshimura Hirofumi, insisted on this priority in talks with Takaichi, and on December 5, 2025, the Takaichi Cabinet prepared a draft legislation for the next Diet session that would reduce the number of Lower House seats from 465 to 420.

This issue is not new for Ishin. In Osaka, Ishin pushed for major reductions in the number of prefectural and city assemblies. In 2011, the Osaka prefectural assembly was reduced from 109 to 88—an almost 20 percent reduction, by far the largest in Japan. Recently, in 2023, an ordinance was passed cutting Osaka city council seats from eighty-one to seventy.

In the last extraordinary Diet session, the LDP and Ishin submitted a bill on Lower House seat reduction. In this bill, the number of members of the Lower House will be reduced to no more than 420 seats, which would be a cut of roughly 10 percent of the current total. The bill also includes a stipulation that if there is no consensus among political parties by the end of the year, twenty-five seats of single-member and twenty of proportional representation seats will be automatically cut. At a Budget Committee Q&A, when asked by a CRA member about this 10 percent reduction, Takaichi responded by reminding him that the Democratic Party of Japan had made a similar proposal.2 The 2026 LDP Election Manifesto explicitly states that the LDP will pass a bill guaranteeing the 10 percent seat reduction in the next Diet session. Reducing the size of the legislature seems to have support among the Japanese public. In a December 2025 Nikkei Shimbun poll, 56 percent of respondents want both fewer Diet seats and electoral system reform. A Yomiuri Shimbun poll in the same month revealed 78 percent of their respondents approve of reducing legislative seats. Last month’s Jiji Press poll showed that 56 percent approved of the legislation drafted for the next Diet session. The appetite for political reform is growing.