Previewing This Weekend’s ASEAN Summit

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

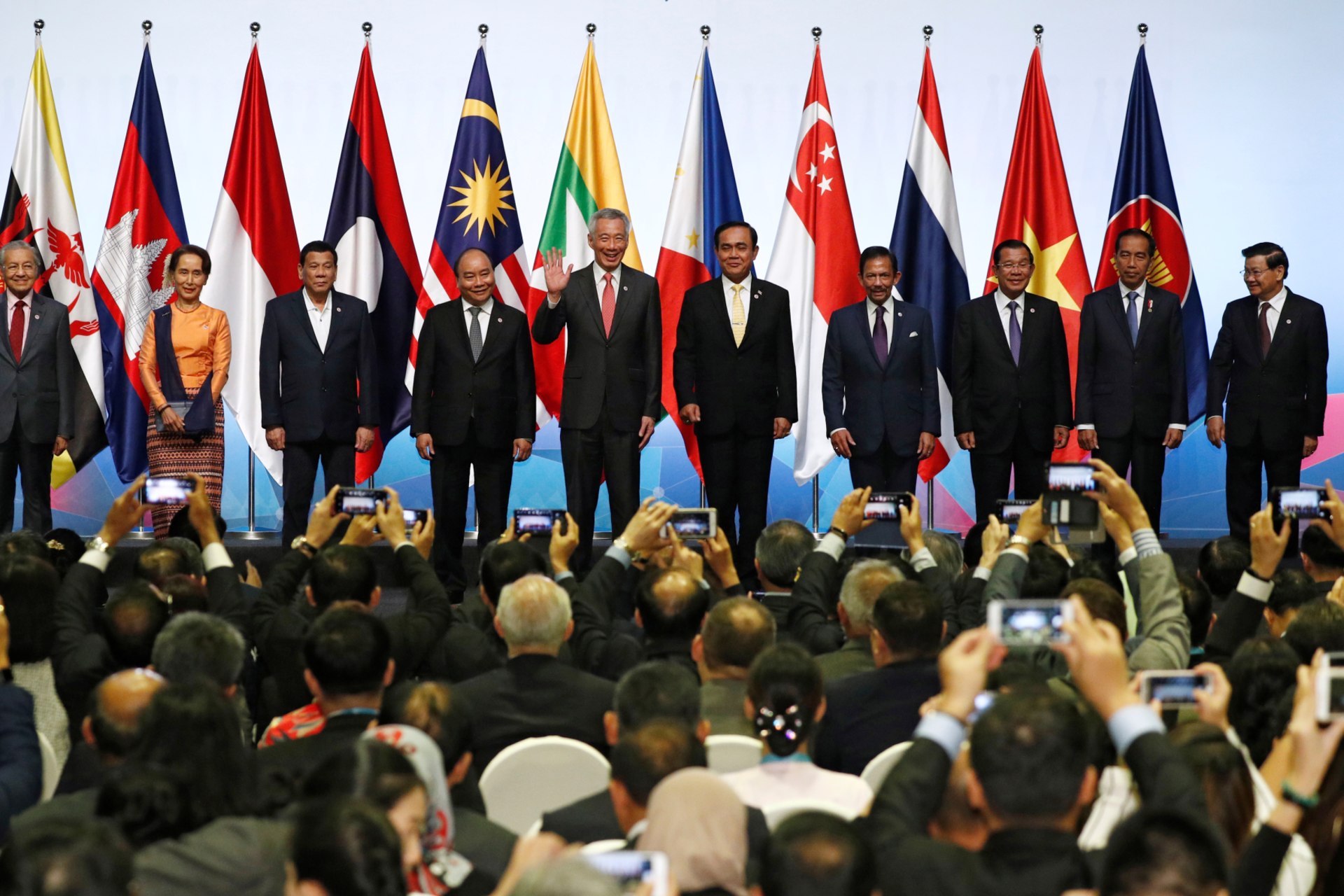

The summit this weekend of leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), held in Bangkok, will probably be less contentious than some of the ASEAN summits earlier this decade, when the organization’s divides over China were plainly on view. Still, there are several key issues to follow when the ten leaders meet in the Thai capital.

1. Prayuth Chan-ocha as the chair. Prayuth, newly confirmed as Thailand’s civilian prime minister, will head the meeting, since Thailand holds the rotating chair of ASEAN this year. Thailand has been aggressively advertising the meeting, probably to use it as a sign that Prayuth is in firm command, and that the event will signify his transition from coup leader to civilian leader. Prayuth will get the warm welcome he seeks. Although some other ASEAN leaders may be uncomfortable with a chair who launched a coup against an elected government, ASEAN’s norm of noninterference in other states’ affairs, and the fact that all the leaders probably will have to work with Prayuth for a long time, will muffle any comments about how Prayuth became Thailand’s civilian prime minister.

2. The ASEAN Indo-Pacific Outlook. The ten ASEAN states will probably approve and reveal a vision for the region called the “ASEAN Indo-Pacific Outlook,” which will emphasize ASEAN’s centrality to the region—although, the outlook will likely be so vague that it will be hard to glean much more from it. But there are already tensions among key states about aspects of the vision; Singapore reportedly is wary of the concept, which has long been pushed by Indonesia as a counterpart to the regional visions that have been developed by the United States, Australia, France, and Japan, among others. It is possible that these tensions will keep the vision from being revealed at the summit.

3. The ongoing crisis for the Rohingya. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh after ethnic cleansing in Rakhine State; smaller numbers have fled to ASEAN member-states including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Although the issue of whether, and how, Rohingya refugees could be repatriated will definitely be a major area of discussion at the summit, ASEAN states likely will play down any criticism of the Myanmar government, given ASEAN’s usual practice of not harshly criticizing member-states. Thailand’s foreign minister already has said that the group will not be “pointing out who is right or wrong” regarding the Rohingya issue—despite the fact that the UN, and numerous rights agencies, have accused the Myanmar military and government of abetting genocide and crimes against humanity. Indonesian President Joko Widodo likely will push the Myanmar government to make real progress on promoting peace in Rakhine State and ensuring safety for Rohingya returning there; right now, it would be unsafe for Rohingya to return. But he could easily get the cold shoulder from the Myanmar government, which has bristled at even the mildest critiques and suggestions from neighbors.

4. Trade tensions. Although the ASEAN states have few options, they surely will spend considerable time discussing what, if anything, Southeast Asia can do as the region is increasingly caught up by regional trade current, including the escalating trade war between the United States and China. The trade battle has actually had some positive, short-term impacts on ASEAN states like Vietnam, a location that is absorbing outflows of investment leaving China. But overall, an extended trade battle will seriously concern many Southeast Asian states, especially those, like Singapore, whose economies are almost totally trade dependent. The countries likely will discuss the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, but there is little indication the deal will be completed anytime soon; the massive agreement has so many potential stumbling blocks.

5. China. With Thailand as the ASEAN chair, instead of Singapore (last year’s chair) or Vietnam (next year’s chair), China may have more leverage within the group; Thailand and China have much warmer relations than China does with Vietnam or Singapore. When Cambodia was chair, in 2012, Beijing appeared to wield significant leverage over ASEAN meetings. Thailand is far more powerful and independent than Cambodia, but China still likely will have more sway than it did last year or will next year. However, it is unlikely that ASEAN will agree on a proposed South China Sea code of conduct with China during this summit; there remain deep tensions within the organization about the proposed code, and a Chinese vessel just last week rammed a Philippine fishing boat in disputed waters, angering Filipinos.