The Trump Shock That Wasn’t (At Least Not Yet)

The “core” U.S. trade deficit is still expanding, thanks to strong electronics imports.

President Trump’s tariffs have been a profound shock to the global trade rules.

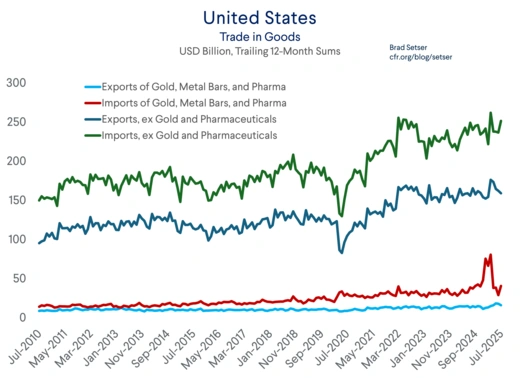

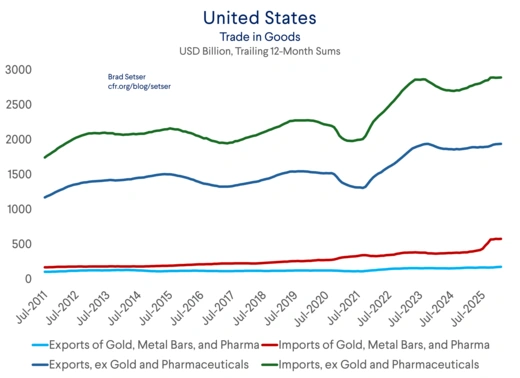

They have generated enormous volatility in measured trade flows.

But so far the volatility has essentially come from pharmaceuticals and gold (including gold bars, or imports of “metal forms”). The impact of the tariffs core trade flows—and hence the global economy—has been modest, at least so far.

America’s trade partners should breath a sigh of relief every time the U.S. announces record tariff revenues—the surge in revenue implies that Americans are continuing to import and just paying the tariff.

It is hard to overstate the Trump shock to global trade rules.

The U.S. has gone from low-bound tariffs (tariffs on about half of industrial goods were zero a few years back, and the U.S. had committed to keeping them low—with any adjustments through standard trade remedies taking time and requiring a fair amount of legal process) to high and essentially unbound tariffs.

The U.S. has gone from tariffs that treat all WTO members were treated equally (that is the meaning of most-favoured-nation, all countries are treated as well as the most-favoured-nation) to a world of bespoke tariffs. Importers of the same good will pay different tariffs depending on the origin of the good (50 percent for India and Brazil, 30 percent for China plus any section 301 duty, 20 percent for Vietnam, 19 percent for Indonesia, 15 percent for Korea, Japan, and Europe, 10 percent for Australia and the UK and nothing for USMCA compliant trade not subject to sectoral tariffs.)

Demanding rules of origin presumably will now be a feature of nearly all U.S. trade—not just trade seeking to benefit from the North American Free Trade Agreement (USMCA). Though in many cases those rules remain to be worked out (and rather confusingly, the rules of origin seem to be part of the transshipment discussion).

All this is a profound rejection of the basic rules of the WTO—which haven’t just been rejected for trade with China, but for all trade.

The dollar value of imports has swung by more than during COVID or the Lehman shock.

The annualized monthly trade deficit rose to a peak of $2 trillion in March before dipping to $1 trillion and then rebounding to $1.2 trillion in July (which is where it started, more or less).

But most of the volatility has come from two categories: pharmaceuticals (where trade is heavily distorted by tax and companies can easily front-run tariffs by stockpiling active ingredients) and gold.

Take out pharmaceuticals and gold and U.S. trade looks, well, rather normal.

To be sure, imports from China (where hefty tariffs were expected) tanked. But imports from Taiwan and Southeast Asia (which were only subject to a 10 percent tariff before Trump started delivering letters setting out his “deal” terms) soared. Total imports from Asia aren’t yet down in any significant way.

There is evidence that the tariffs have slowed imports of autos (expect a big dip in September as European and Japanese importers wait for the finalization of their “deals” and a reduction in the 232 auto tariff to 15 percent; waiting for tariff relief will replace front running as a theme.)

But imports of electronics are up substantially (imports from Taiwan are up over 50 percent YTD) on the back of booming investment in data centers for advanced statistical analysis to backstop large language models (“AI”)

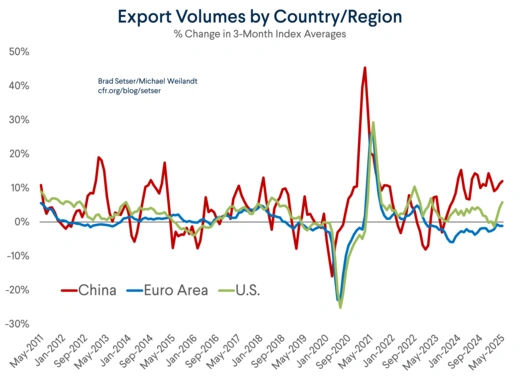

So global trade has actually held up rather well even though the world’s largest economy (and largest source of demand for imports of manufactures) is openly flouting the “rules”.*

A key question, of course, is how long this will last.

The August deals and letters resulted in hefty tariff increases for many countries (tariffs on Southeast Asia doubled relative to April).

If the current tariff wall stays in place (roughly 15 percent average tariffs, albeit with substantial variation across countries and sectors), there should be some impact on trade flows.

The roughly 15 percent average tariff increase on trade with China in trump’s first term reduced trade by roughly 30 percent with the portion of trade subject to 25 percent tariffs falling by closer to 50 percent (bringing the effective tariff increase down to around 10 percent).

But the bilateral tariff elasticity of 2 is too high for a global tariff increase—remember that firms shifted final assembly to southeast Asia to get around the bilateral tariffs, and with no limit on embedded Chinese content so long as there was a tariff code shift, actual imports of Chinese content didn’t change much.

The import elasticity for exchange rate moves is closer to 0.3 or 0.4—so a 15 percent tariff might be expected to reduce impacts by 5-6 percent. That is a year or two of normal import volume growth—a meaningful impact, but nothing like COVID or global financial crisis. Some countries will be able to offset reduced U.S. sales by taking market share from US exports (who faced increased input costs on imports).**

As a share of GDP, non-petrol imports would thus fall from ~10 percent of GDP to 9.5 percent of GDP or a bit less.

So far at least it is hard to see strong evidence of this kind of impact.

U.S. imports are, more or less, on trend (with front-running pulling imports forward to Q1 just a bit).

The high frequency measures of global trade haven’t really slowed.

The liberation day shock to the trade rules was thus bigger than the shock to overall trade flows.

Let’s though see what judgement day brings, and what the data for the fall shows—there should be more of an impact than is now apparent.

* And possibly operating outside the scope of U.S. trade law; the court for the federal district noted that tariffs should originate in Congress and thus cannot change without congressional assent absent an explicit delegation of authority to the executive branch.

** An actual exchange rate depreciation increases exports as well as lowering imports, as the export price elasticity is higher than the import price elasticity (though it now works off a smaller base).