Accelerating technological change, including automation and advances in artificial intelligence that can perform complex cognitive tasks, will alter or replace many human jobs. While many new jobs will be created, the higher-paying ones will require greater levels of education and training. In the absence of mitigating policies, automation and artificial intelligence are likely to exacerbate inequality and leave more Americans behind.

Technology has been the biggest cause of job disruption in recent decades, and the pace of change is likely to accelerate. Computers and robots can now recognize and respond to human speech and translate languages; they can identify complex images such as human faces; they can steer cars and trucks; they can perform medical diagnoses and assist in surgical procedures. The United States has already been living through the era of machines replacing physical labor; a typical U.S. steel mill today produces five times as much steel per employee as it did in the early 1980s, and productivity gains are similar across other leading goods-producing industries. Computers have also replaced or altered many routine service occupations, including travel agent, switchboard operator, secretary, and file clerk. In the coming era, computers will augment or replace tasks in many cognitively based occupations as well, from legal research to medical diagnosis to financial advice, and machines with the capacity to learn will get better at these tasks over time. Advances in artificial intelligence will mean that machines will become able to outperform humans in areas of perception (as seen with driverless cars) as well as pattern recognition and calculation (which will aid medical diagnosing). Digitalization of the workplace has already been transformational—as Mark Muro and his colleagues at the Brookings Institution have put it, computerization is “like steam power or electricity, so broadly useful that it reorients the entire economy and tenor of life.” They estimate that in the twenty-first century the number of U.S. jobs requiring high levels of digital skills has more than quadrupled already, from 5 to 23 percent of total employment—about thirty-two million jobs—while the number of jobs requiring little in the way of digital skills has fallen from 56 percent to less than 30 percent.14

Is the United States facing a coming age of mass unemployment, in which machines will do most of the work once reserved for human beings? The most dramatic estimates have suggested that nearly half of all jobs in the United States could be replaced by automation, and the effects would be felt more acutely by those with lower levels of education.15 Research by MGI suggests a narrower but still significant result; about 5 percent of occupations could be fully automated with existing technologies, but most occupations will still be affected in some way by automation. The MGI study estimates that in about 60 percent of all occupations, especially more routine jobs, at least 30 percent of job tasks are potentially automatable.16 Occupations that are especially vulnerable include manufacturing, food service, and retail trade; the White House Council of Economic Advisers has estimated that more than 80 percent of jobs paying less than twenty dollars per hour could be automated.17 Nearly three million Americans drive trucks for a living, for example, and could lose their jobs as self-driving vehicles are more widely deployed. Nearly five hundred thousand brick-and-mortar retail jobs have been lost over the past fifteen years, while the expansion of e-commerce has created fewer than two hundred thousand new jobs.18 Nearly 25 percent of African American workers are concentrated in a handful of occupations that are highly susceptible to automation, such as retail salesperson, cook, and security guard.19 But automation will also affect better-paid occupations, such as financial analyst, doctor, lawyer, and journalist. Any work tasks that can be routinized even in part are subject to replacement by computers or robots, and advances in artificial intelligence will steadily increase the number of occupations affected.20

Nearly two-thirds of the 13 million new jobs created in the U.S. since 2010 required medium or advanced levels of digital skills.

Whether these technologies will destroy more jobs than they create is impossible to know with any certainty. Data are currently inadequate on how workplaces are adopting and incorporating emerging technologies. Economic history suggests that technological advancements spin off new forms of work; the occupation of web developer, for example, did not exist until the early 1990s, and last year employed 150,000 Americans at a median salary of $66,000.21 Self-driving cars and smart technologies will require human maintenance and repair, creating new blue tech jobs for those with sophisticated repair skills. In the two decades ending in 2012, employment actually grew faster in fields that were being rapidly computerized, such as graphic design, than in those that were automating more slowly.22 The new technologies are also coming into the workplace at a time when the workforce is aging rapidly and new positions are opening due to retirements; the graying of the baby boom generation has even led some employers to try to retain their older workforce past normal retirement age.23

There is far more agreement that technology already has caused, and will continue to contribute to, polarization of the workplace. Occupational structure has been polarizing in all the advanced economies.24 Nearly two-thirds of the thirteen million new jobs created in the United States since 2010, for example, required medium or advanced levels of digital skills; mean annual wages in the highly digital occupations are more than double those in occupations that require only basic digital skills. Basic familiarity with spreadsheets, word processing, and customer relationship management software is becoming a baseline requirement for many positions.25 A distressing shortage of women and minorities acquire these middle and advanced digital skills, leading to still more wage disparity. In addition to the demographics of aging, employers need to take full advantage of the diversity of the U.S. population to maximize their success and to solve problems with the nation’s full creative capacity.

As technological sophistication increases the complexity of work environments, demand is growing for employees who excel at skills that machines cannot replicate, at least currently: empathy, teamwork, collaboration, problem solving, critical thinking, and the ability to draw connections across disciplines. Many of the higher-paying new jobs are based on creativity and successful interaction with colleagues rather than on more efficient accomplishment of a narrow set of tasks. As the cognitive capabilities of machines expand, technical education in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) will increasingly need to be supplemented with design thinking, entrepreneurship, and creativity, areas where Americans excel.26 More Americans will need to complete postsecondary education. Occupations that require a college education or advanced degree will grow over the next decade and beyond, whereas employment in occupations requiring only a high school education or below will decline.27

Concerns over technology-led disruption are far from new.28 Economist John Maynard Keynes warned in 1931 of widespread unemployment owing to technology.29 In 1966, the National Commission on Technology, Automation, and Economic Progress, established by Congress during the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, said that “the fear has even been expressed by some that technological change would in the near future not only cause increasing unemployment, but that eventually it would eliminate all but a few jobs, with the major portion of what we now call work being performed automatically by machine.”30 The evidence does not suggest the United States is today, any more than it was in 1931 or 1966, on the cusp of an era of widespread, technology-induced unemployment. A more moderate view predicts that some jobs will be lost due to automation, and the adjustment will be especially challenging because many of the new jobs being created will require significantly higher levels of education and skills. In the absence of countervailing efforts, more Americans are likely to be pushed into lower-wage work.

Whether adoption proceeds rapidly or moderately, many workers will need to adapt to changing work tasks or switch to new occupations entirely. A policy of waiting and hoping that the market will sort out the challenges, however, is not an adequate response. Failure to provide the education, training, and resources that Americans need to seize these new opportunities, and to use policy tools to spread the benefits of technology more widely, will leave millions of Americans to face lives of diminishing prospects.

Embracing technological innovation and speeding adoption are critical for U.S. national security and economic competitiveness. Openness to trade and immigration are also vital for maintaining U.S. technological leadership.

While technological change presents significant economic and social challenges, preserving technological leadership remains vital to U.S. national security and economic competitiveness. If the United States loses its technological edge, its standing in the world will be threatened. U.S. rivals understand this clearly; China’s push for “indigenous innovation” and its Made in China 2025 plan for $300 billion in government-directed subsidies are aimed at making China a world leader in advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, electric cars, 5G mobile communications, and bioengineering.31 In July 2016, Beijing outlined an ambitious plan to become the world’s leader in artificial intelligence by 2030, surpassing the United States. China has also advanced mobile internet and applications at a staggering pace and now seeks to export them to the world. If successful, these initiatives would both bring huge commercial gains to China and also help build the capability for China to rival the United States militarily.

The good news is that the United States is still the world’s leader in the development and diffusion of new technologies. Total U.S. R&D funding reached an all-time high of nearly $500 billion in 2015, nearly 3 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), with 60 percent of that coming from the private sector.32 The United States has all the right ingredients to remain a technological leader—an entrepreneurial culture, a favorable regulatory environment, a developed venture capital industry, and most of the world’s leading research universities.33 It can and should continue to build on those strengths.

There are some worrisome signs, however. Federal funding for R&D, which goes overwhelmingly to basic scientific research, has declined steadily and is now at the lowest level since the early 1950s, even as other countries, such as Brazil, China, Singapore, and South Korea, are accelerating their investments.34 State government support for public research universities has also fallen sharply because of state budget constraints.35 Some nations are inducing or pressuring U.S. companies to transfer technologies and manufacture these innovations locally as the price of investing.36 A 2013 commission led by Jon Huntsman, the current U.S. ambassador to Russia, and Admiral Dennis Blair, the former director of national intelligence, found that intellectual property theft was costing the United States hundreds of billions of dollars each year and seriously eroding its innovative edge.37

Public concerns about technology are also growing. An October 2017 Pew Research Center poll found that three-quarters of Americans are worried about a future in which computers and robots will do many jobs, fearing that job prospects will diminish and economic inequality will worsen.38 Fortunately, there are so far few signs of any concerted efforts to retard the adoption of technology. Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates’s proposal for a tax on robots that replace human workers found few backers; the European Parliament in 2017 rejected a similar proposal to tax robots to pay for retraining workers they displace.39 If regulations were adopted to discourage new technologies, they would harm U.S. economic prospects. Those companies that have been the most aggressive in disseminating new digital technologies, forexample, have grown faster than companies that have been slower to digitize. MGI estimates that the United States has captured only 18 percent of its potential from digital technologies in terms of faster growth, higher productivity, and benefits to consumers.40 The United States has benefited immensely from the success of its high-technology clusters in the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, Route 128 in Boston, Silicon Valley, and dozens of other innovation hub cities across the country, such as Ann Arbor, Austin, New York, and San Diego. These are successes that the rest of the world is still trying to emulate. But without policies that continue to promote the development and rapid commercial adoption of technological advances, the United States risks falling behind in the competitive global landscape.

Accessing the fast-growing overseas markets and welcoming talented immigrants from around the world are also vital to U.S. success in the economic race of the twenty-first century. The most successful American companies are operating on a global scale, investing and selling their goods and services both overseas and in the United States. Washington needs to do more to enforce strong trade rules, intellectual property protection, and labor standards in trade agreements and trade preference programs. The trade agenda should also include a concerted effort to press other countries to raise wages in order to create new sources of growth for the world economy. But a United States that turns its back on trade opening—as the Donald J. Trump administration did by walking away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement in the Asia-Pacific and threatening to leave the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico—will seriously diminish prospects for its best companies and for its workforce.

Immigration restrictions, particularly on highly skilled migrants, would be similarly harmful. American universities still attract the lion’s share of the best foreign students, and immigrants have played vital roles as entrepreneurs and engineers in Silicon Valley and other U.S. innovation hubs.41 But there are worrisome signs of a drop-off in foreign student enrollment, and the Trump administration has been rolling out a series of measures that will make it increasingly difficult for highly skilled immigrants to work in the United States.42 At the same time, China is opening its doors wider than ever before to foreign workers, especially those with science and technology training.43 The United States today is in a global competition to attract and retain the best immigrants and should embrace policies that seek to enhance the economic contributions of immigrants, rather than seeing them as competition for scarce U.S. jobs. If the country fails to win that competition, it will lose investment, jobs, and growth.

U.S. entrepreneurship also needs to be revitalized. The rate of new company formation has been slowing for decades, and that slowdown has accelerated since the turn of the century, likely driven by lack of access to capital and the growing dominance of a smaller number of large companies.44 Fewer young companies are reaching the stage of rapid and explosive growth that has in the past been such a big contributor to job creation.45 The slowdown has been especially evident outside high-growth cities; from 2010 to 2014, even as the economy was recovering, counties with one hundred thousand or fewer residents lost more businesses than they created.46

Technology does not see borders. In the absence of a workforce with the right skills and opportunities, without a regulatory regime that favors innovation, without access to global markets, and without state and local policies that favor the development of successful clusters, the United States will not realize its full potential in the economy of the twenty-first century. U.S. companies, as well as its smartest scientists and innovators, can move internationally to take advantage of opportunities and better enabling environments, whether the quality of the workforce or the regulatory environment. The best and the brightest can choose other countries to launch and build their businesses. The loss of technological leadership would weaken U.S. national security and diminish economic prospects for Americans. The United States should find new ways to expand its technological leadership while creating better employment opportunities for more Americans.

Strong economic growth that leads to full employment has been the most consistently successful approach for raising the wages of Americans.

Strong and sustained economic growth is needed to create better job opportunities in the future. Any discussion about the jobs of the future will be moot if the economy is not growing rapidly enough to create many new jobs. Economic policies that maintain strong growth and full employment are therefore needed just to set the table to meet the deeper challenges brought on by rapid technological change. Over recent decades, periods of strong growth have been the few bright spots amid generally discouraging trends in the U.S. labor market.

Wage growth has been weak for U.S. workers for decades now, averaging just 0.2 percent annually since 1973. For wages to grow steadily for most workers, their productivity needs to rise (which comes from better education and training and from investments in new technologies), their share of the gains needs to be stable or rising, and wage gains need to be broadly shared across income groups.47 Those conditions have not existed in a consistent way for several decades. Improvements in labor productivity, or output per worker, slowed substantially after 1973 and have been particularly anemic for more than a decade. The share of income gains going to the workforce has also fallen. After remaining stable for three decades after World War II, the U.S. labor share of income has fallen as the corporate share has grown; labor’s income share, which was close to 65 percent in the mid-1970s, is today below 57 percent.48 U.S. wages used to track quite closely with increases in productivity but began falling behind in the late 1970s. And where labor has made gains, these have overwhelmingly gone to the best-paid workers. Since 1979, wages for those in the top quintile of income have risen 27 percent in real terms, from thirty-eight dollars per hour to forty-eight dollars per hour. But the bottom quintile has seen a slight fall in real wages, and those in the next two brackets have seen little gain.49 The United States is not alone here: most of the advanced economies have seen rising inequality in wage earnings and a falling labor share of income. But the polarization has been more extreme in the United States than in other similar economies.50

The best antidote to these polarizing trends has been a strongly growing economy that is at or near full employment (an economy in which unemployment is low, temporary, and mostly associated with voluntary job changes). Since 1980, the U.S. economy has reached full employment just 30 percent of the time, compared to 70 percent between the late 1940s and 1980, when wage growth was far stronger.51 In the aftermath of the Great Recession, it took nearly a decade for the unemployment rate to fall back to the prerecession level. Official unemployment today is near 4 percent, but the broader measure of unemployment, which includes those marginally attached to the labor force and those working part-time who seek full-time employment, is over 8 percent.52

Full employment has been the best predictor of wage growth over the past forty years. The strongest period of real wage growth came during the booming economy of the second half of the 1990s. Over the past two years wages have risen faster for lower-wage workers than for higher-wage workers, likely as a result of a tighter labor market and minimum-wage increases in some states and cities.53 The story is similar in terms of labor’s share of the national income. Labor’s share fell sharply during the recession of the early 1980s, but then rebounded strongly with the recovery in the second half of the decade. The labor share fell again in the early 1990s, but grew strongly in the last half of that decade to again reach mid-1970s levels; by 2000, unemployment had fallen to just 4 percent and labor force participation hit an all-time record of more than 67 percent. The decline in the labor share of income was steepest in the 2000s, falling throughout the decade and accelerating during the 2001 recession and the Great Recession.54

In addition to strong growth, more targeted measures may be needed, particularly to boost earnings for those in service sectors such as health care or retail, where productivity growth has been slower. The U.S. economy has had and will continue to have enormous demand for personal service occupations of all sorts. Jobs for home health and personal care aides, for example, are predicted to grow by 40 percent, or an additional 1.1 million jobs, by 2026. But the median pay is just under $22,000 per year.55 Other occupations that will see the largest growth in total numbers include generally low-paying jobs such as fast-food worker, cook, janitor, and house cleaner.56 Compared with those of other advanced economies, the U.S. labor market is particularly polarized—among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, the United States has a higher share of working poor (defined as earning less than half the median income) than any other country except Greece and Spain.57 A boost in the minimum wage could benefit some of these workers, as could expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) or other tax policies linked to work. Youth unemployment, which is roughly double the national average, is another area where targeted approaches may be needed. Successful initiatives have included Jobs for America’s Graduates, which focuses on reducing high school dropout rates, and Generation, which operates in five countries and ten U.S. cities to offer training in job skills for young people.58

Finally, efforts should be made to revitalize struggling communities, many of which boast strong histories of economic success secured through some now-obsolete industry or asset. Often, struggling communities are concentrated in similarly struggling regions—for example, the industrial Midwest and Appalachia—and have high levels of unemployment and disinvestment tied to their former success in now-antiquated industries. Revitalization of these communities hinges on attracting talented and entrepreneurial individuals, facilitating investment in more diverse industries, and ensuring that native residents have access to workforce development and entrepreneurial tools to optimize their productivity. Policies and practices that encourage their homegrown best and brightest to remain are needed if these communities are to be viable over the long term. One in every six Americans is living in an economically distressed community where job prospects have continued to shrink. In these communities—which include large cities such as Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, and Newark— employment has continued to fall since the end of the Great Recession. Education is a big divider here; in more prosperous cities, nearly half the residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, whereas in the poorer cities, the figure is just 15 percent.59

Immigration could also play a significant role. Canada has pioneered models that allow poorer provinces to attract immigrants who can create new economic activity in their regions. And the sorts of company-educational partnerships discussed below could help make struggling regions a more attractive place for employers to locate. For many companies, the availability of an appropriately skilled and trained labor force is the single greatest factor in determining where to establish or expand operations.

The lack of accessible educational opportunities that are clearly and transparently linked to the changing demands of the job market is a significant obstacle to improving work outcomes for Americans.

The United States became the world’s most successful economy in the early twentieth century not just because of its plentiful agricultural land and rich endowment of natural resources, nor simply because of the hard work and entrepreneurial ambitions of its people. The critical ingredient was education. As the huge technological breakthroughs of the era came onstream—including electricity, the automobile, the telephone, and air travel—the demand for a more highly skilled workforce to take full advantage of these new capabilities surged.60 And the United States responded by far outpacing any other country in expanding high school education to most of its citizens and establishing the state university systems.

From 1910 to 1940, just as modern techniques of mass production were being spread across the country, the number of fourteen- to seventeen-year-old Americans attending high school rose from 18 to 73 percent, and high school completion rose from 9 to 51 percent.61 No other country even came close to achieving these levels until decades later. Most of the progress was led by state and local governments and citizen groups seized with the urgency of extending free education to as many young people as possible, not by the federal government. Most of these students did not go on to college but rather went directly into the workforce, with high school completion marking the essential credential needed for most to succeed. After World War II, similar rapid progress was extended to postsecondary education. The GI Bill, passed by Congress in 1944, offered free college education to every one of the nation’s sixteen million World War II veterans. The bill, coupled with the spread of affordable, subsidized state universities, allowed both college enrollment and completion to soar.

The number of job openings nationwide is near record level, yet many employers say they struggle to find the employees they need.

Today, although the United States has continued to make progress in raising the educational achievements of its citizens, its educators, students, and employers have not adjusted sufficiently to the demands of a changing labor market.62 Increasingly, the challenge is not just providing more education but providing better-targeted education that leads to better work opportunities, even as the target will continue to shift as new technologies are adopted. The number of job openings nationwide—nearly six million—is near record level, yet many employers say they struggle to find the employees they need.63 The challenges exist not only in higher-paying jobs in information technology and business services, but also in a range of middle-wage jobs, from nursing to manufacturing to traditional trades.64 The primary focus of the educational system has continued to be formal education for young people—increasing high school completion rates and expanding college enrollment and completion. But that system is too often inadequate in preparing Americans for many of the faster-growing, better-paying jobs in which employers are looking for some mixture of soft skills, specific technical skills, some practical on-the-job experience, and a capacity for lifelong learning. Employers, for their part, have been slow to develop or expand their own training systems to fill in the gaps from the educational system.

While education, appropriately, has many goals beyond just preparing students for the job market, Americans increasingly believe that job preparation is a crucial mission for educators. The 2017 Phi Delta Kappa poll on attitudes toward public schools found that Americans want schools to “help position students for their working lives after school. That means both direct career preparation and efforts to develop students’ interpersonal skills.” Specifically, while support for rigorous academic programs remains strong, 82 percent of Americans also want to see job and career classes offered in schools, and 86 percent favor certificate or licensing programs that prepare students for employment.65

Making job preparation an education priority will require transformations that are every bit as dramatic as those that came about in the early part of the twentieth century. The goal should be to ensure that all students can develop the knowledge, aptitude, and skills to succeed in a rapidly changing labor market, and are able to continue to build those capacities throughout their working lives. That will require more hands-on involvement by employers and more options outside traditional classroom education—such as apprenticeships—so that students can gain the skills needed for better-paying jobs. Further, addressing this challenge calls for expanded counseling for students to set them on successful education-to-work paths, better credentialing systems to signal market demands more clearly, and transparent data to allow students, employees, and employers to make better educational, career, and hiring choices.

Many Americans have responded to market signals about the value of a college education. Over the past three decades, the earnings gap between those with a college education and those who have only completed high school has doubled.66 On average, a high school graduate today will earn $1.4 million over the course of his or her life, while the average holder of a bachelor’s degree will earn $2.5 million, and the typical professional-degree holder roughly $4 million.67 Since 1980, the percentage of Americans aged twenty-five and over who have completed four-year college degrees has risen from 17 to 33 percent, a significant increase. Those numbers conceal large inequalities— 80 percent of children growing up in the richest 20 percent of U.S. households go to college, and 54 percent complete their degrees on time; for those from the poorest quintile, however, only 29 percent go to college and just 9 percent finish on time.

But the market signal has become less distinct in the twenty-first century. While returns from a four-year degree are still large, real wages for young college graduates—except for those who also have an advanced degree—have risen only slightly since 2000.68 Disparities in the market value of different majors are huge; the median starting salary for a four-year graduate in computer and information sciences, for example, is more than $71,000, while that for an English major is just over $36,000.69

Educational institutions will need to get better at tailoring certain programs to labor market signals. Among liberal arts students, for example, those who bolster their education with additional technical skills, such as graphic design, social media, data analysis, or computer programming, roughly double the number of entry-level jobs available to them and can see an estimated $6,000 bump in initial salary.70 Finally, too many students are borrowing heavily for an education whose returns are unclear. The cumulative debt load for students has more than doubled in the past decade, from $600 billion in 2007 to roughly $1.3 trillion today, while the average debt per student has increased from $15,000 to more than $25,000.71

Many excellent career opportunities are also available to those who attend two-year or associate’s degree programs; Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce estimates that even with the decline in manufacturing employment, there are some thirty million good jobs in the economy, paying an average of $55,000 per year, for those without a four-year degree.72 While most colleges have programs leading to work in higher-compensation fields such as technology, engineering, and math, about two-thirds of students at community colleges—and half at for-profit institutions—are enrolled in general studies programs, many in hopes of eventually getting a four-year degree. The majority of community college students say they hope to transfer and complete four-year degrees, but an astonishingly low 12 percent ultimately receive a bachelor’s degree.73 And they are forgoing the opportunity to earn associate’s degrees or certificates in well-paid fields such as medical and information technology and business and retail management, where employers say they have a hard time finding qualified candidates.

Other types of education, such as micro-degrees in technology-related occupations, can have real value in the job market with much less upfront investment by students, though they need to be more widely recognized by employers. Online providers such as Coursera and Udacity are expanding their offerings of these sorts of targeted credentials. And work-based learning programs of various types—from traditional apprenticeships to paid internships—can both lower the cost of additional education and help employers develop a pipeline of future employees.

For most Americans, their educational choices will be the most economically consequential decision they make in their lives. They need to be empowered with the resources, information, and opportunities to make the best decisions possible.

Educational offerings and the employment opportunities available for graduates are too often mismatched. There is a lack of alignment between learning and work that requires better use of data, better career counseling, and more involvement by employers.

Both educators and employers need to participate more effectively in building the workforce of the future. Personnel hiring decisions may be the most important ones that any employer makes, yet most employers make those decisions entirely on the spot market.74 No company would leave its acquisition of critical raw materials or components to the last moment, but most hiring decisions are made as jobs come open. Employers find themselves competing for often scarce pools of talent, without developing and deepening those talent pools themselves. According to a Harvard Business School survey, just one-quarter of companies have any type of relationship with local community colleges to help prepare employees with the skills they need.75 Not surprisingly, given their lack of involvement, many companies complain that too few graduates leave school with skills that employers are demanding. A study by IBM, for example, found few courses being offered nationwide in such strong job-growth areas as cloud computing, data analytics, mobile computing, social media, and cybersecurity.76

A successful workforce model for the twenty-first century will require a different mind-set. Employers need to think about not just competing for talent, but also how to develop the pipeline of talent they need to build their workforce. That will require greater collaboration

For most Americans, their educational choices will be the most economically consequential decision they make in their lives.

not just with educational providers but also with other, even competing, employers. Employers should embrace collaborative approaches to talent development; big gains could be made, for example, by industry sectors working together to ensure a steady flow of properly educated and trained students for their future workforce. Educational institutions need to be open to working more closely with employers, without compromising the other elements of their educational mission.

A variety of approaches has proven successful. Many community colleges have been expanding their efforts to partner with employers and to identify in more systematic ways the labor market outcomes for graduates from particular programs. Miami Dade College, forexample, has set up programs in animation and game development, working with companies such as Pixar Animation Studios and Google; a program in data analytics, working with companies including Oracle and Accenture; and a physician assistant program, working with local hospitals. Salaries for graduates of these programs far exceed the norm for community college graduates.

Some larger companies are working closely with community colleges and universities to design certificate programs that lead more directly to employment; these programs often include work-study elements that allow students to do internships or apprenticeships at the companies for which they wish to work. Altec, the Birmingham-based provider of trucks, cranes, and other products and services for the telecommunications and electric utility markets, has established close relationships with the educational providers in all its major factory locations. These include many towns and smaller cities, such as Elizabethtown, Kentucky, and China Grove, North Carolina, where finding a skilled labor force within commuting distance can be a challenge. These geographic partnerships, which involve companies, educational providers, and state and local governments, need to be expanded, which will require initiative from the private sector and responsiveness from educational institutions.

Toyota, the Japanese automotive company, has built its own advanced manufacturing technician program to provide a pathway for students seeking careers at the company. The goal is to create a reliable pipeline of “global-quality technical talent” for its U.S. operations, allowing those plants to remain world leaders. The program begins with exposing students in middle and high schools in communities with large Toyota plants, such as Georgetown, Kentucky, to the possibility of a career with the company.77 Toyota works closely with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as Project Lead the Way to encourage students to acquire the math and science skills they will need. Students who enter the program upon high school graduation undertake a two-year, full-time community college program that mixes school-based learning with paid intern work at the Toyota plant, leading to an associate’s degree in applied science that is effectively paid for by the company. Others may go on to complete four-year degrees that can then lead to senior engineering positions in the company. Importantly, the Toyota program is open—other companies seeking employees with similar skills can become involved if they are willing to offer similar work-study opportunities for students. The program is now operating in nine states on twenty-two community college campuses.

Such work-experience programs are too rare—just 20 percent of adults report having received any sort of work experience as part of their education, and most of that was concentrated in health care and teaching.78 Apprenticeships, which provide work-based education in many technical jobs for those with less than a four-year degree, are relatively rare in the United States; currently there is just one working apprentice for every forty college students in the country.79 Several million jobs, many of them in career paths leading to higher earnings than traditional apprentice occupations offer, could be opened to apprenticeships.80 This could also be a cost-saving measure for employers, who often hire four-year college graduates for positions that could be filled by those with a two-year degree plus relevant work experience. Expanding apprenticeships—some of which could serve mid-career workers as well as new trainees—has been a priority for both the Barack Obama and Trump administrations.81

Scaling up such efforts is going to require more than just single company-led initiatives, however. In particular, better data need to be made readily available to colleges and other educational institutions to help them adopt new curricula in a timely fashion, track the labor market outcomes of their students, and then provide that information to prospective students. Students in the Toyota program know with some confidence the value of the degree they will earn. For most students, however, that information is more elusive. While many community colleges try to track the job outcomes of their students, at least in career and technical education (CTE) programs, they rely on surveys with low response rates and rarely track students beyond the first year after graduation.82 Students need to know with some confidence the market value of particular degrees and certificates, and employers need better ways to signal their demands so potential employees can invest in the skills that are needed. Students need far greater assurance that their investments in education and training—in both time and money—will be rewarded in the job market.

The growth in data about labor market needs and outcomes has been enormous and will only accelerate. The federal government in particular continues to be a critical source of labor market information through its annual randomized surveys, but a growing portion of the data is now in the hands of the private sector, including companies such as Burning Glass Technologies, Indeed, LinkedIn, and Monster. Washington should expand and improve its own data gathering and dissemination, but it also needs to work closely with the private sector to ensure that relevant labor market information is made available quickly to students, educators, and employers.

Significant private-sector and NGO efforts are under way to fill these gaps; the state of Colorado has been a leader here, with a series of education-to-work initiatives supported by the state government, community colleges, employers, data providers, and philanthropic organizations. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has been pilot testing with several states a jobs registry that is intended to provide much clearer employer information to students, educational institutions, and potential employees about the credentials and competencies that are in demand.83 The initiative encourages employers to collaborate in forecasting their future workforce needs and create common definitions to signal those needs.

That information, in turn, can help educational institutions develop or expand programs that lead to higher-quality jobs. One big challenge is aligning credentials with employment opportunities. The current market for educational credentials is highly inefficient, with educational providers offering potential students a bewildering array of thousands of degrees, credentials, certificates, and other markers of attainment, often without any clear knowledge about the market value of these credentials. The Lumina Foundation, in cooperation with the Business Roundtable, has funded the Credential Transparency Initiative, with the aim of bringing greater transparency to the credential market. Through an online application called Credential Engine, the effort pulls together detailed information about the credential offerings of educational institutions across the country, including cost to acquire, breadth of recognition, and comparisons to offerings at other institutions. Employers, in turn, are able to signal through the registry which credentials they are seeking from future job applicants. Over time, the goal is to produce rich data that allow potential students to assess the labor market value of the credentials offered by different educational institutions.84 The data will be open-source, allowing for the development of applications to connect credentials with local or sectoral labor market needs.

Students need far greater assurance that their investments in education and training— in both time and money—will be rewarded in the job market.

Similar transparency is needed in the hiring process. Hiring today has moved almost entirely from traditional newspaper ads to online ads, but there is no agreed technical standard for online hiring. Most postings are not presented in a consistent, machine-readable format that allows for easy sharing or developing targeted applications, and many leave out relevant information, such as wages and skills or credentials requirements. Most job ads are available primarily through third-party websites such as Indeed, LinkedIn, and Monster, which makes it difficult to share the announcements broadly or to aggregate the labor market signals they contain.85 The Obama administration persuaded those companies to cooperate in developing shareable standards for hiring veterans, potentially creating a template for a more open workforce data architecture.86 Larger efforts are needed. Jobs and hiring information is of such broad value to society—much like weather data—that it should be gathered and shared so the broadest possible use can be made by employers, educational institutions, application developers, and others.87

Students also need more active counseling to help them make sensible choices about the relationship between their education and future employment prospects. Small-scale experiments that involve comprehensive advising from college counselors with smaller caseloads and the development of “guided pathways” for students have shown dramatic improvements in graduation rates.88 But the need for good advice goes far beyond the choice of majors or college programs. Almost everyone needs guidance and mentoring to succeed in the labor market; one of the huge advantages that young people from better-off families enjoy is that their parents often have connections to networks of individuals who can open employment doors. Byron Auguste, cofounder of the nonprofit Opportunity@Work, argues that “where the labor market works, it’s because people have guidance—from friends, from parents, from mentors. Everyone needs guidance, but some people get it and some don’t.”89 As online data about the job market improve, both high school and college counselors will have powerful new tools to help students make better, more cost-effective educational choices. For example, the online portal Journeys—a new application being developed by San Diego-based EDmin—will allow both high school and college students, as well as mid-career workers in transition, to chart various educational paths to achieve their career goals.90 Such tools will be enormously valuable for both students and guidance counselors to help inform educational choices. More active involvement by employers in educational settings, either directly or through existing structures like state and local workforce boards, and expanded work-based training opportunities would also help transform career advice for students.

A change in thinking is needed, from seeing education and work as distinct and separate activities to considering them as closely linked.

Workforce skills are a major competitive issue for the United States. Many of the most productive industries in advanced manufacturing, internet services, and other technology-intensive sectors are highly mobile and capable of being located in many different places in the world. Access to a well-educated, high-quality workforce is critical to these companies. And many countries are simply doing better than the United States in training their workers for these jobs. In Canada and South Korea, for example, more than 60 percent of young people are already graduating from postsecondary programs. The United States, which was the leader in educating its people for much of the twentieth century, now has a lot of catching up to do.

A change in thinking is needed, from seeing education and work as distinct and separate activities to considering them as closely linked. For younger students, that means finding new ways—through work-study programs, early job-oriented counseling, internships, or career-related coursework—to allow them to link what they are learning in school to opportunities in the labor market. For older workers, it means building support for lifelong education to allow them to keep up with the changes that technology will bring.

Continuing education, retraining, and improvements in skills throughout an individual’s working life will be critical to success in the workforce as the rate of technological change increases.

The U.S. educational model—and indeed that of most countries— has long been premised on the idea that young people would acquire a certain level of education in their early years, which would provide the necessary knowledge and credentials to serve them throughout their working lives. In the face of rapid technological change, that notion is increasingly obsolete. Most mid-career employees have already seen their working lives transformed by the introduction of computers and information technology; many administrative jobs, including mail sorter and file clerk, have shrunk rapidly. The promised developments in artificial intelligence are likely to intensify the pace of change, requiring Americans to acquire the knowledge to work with and alongside thinking machines. These pressures are forcing many more American workers to retrain and find new skills more often in their careers, either to advance in their own occupations or to find entirely new ones.

Such transitions are not easy. Like learning a foreign language, embracing new technologies is easier for students and younger workers than it is for older workers. Creating a culture of lifelong learning in the work place is going to require changes in behavior by companies and their employees, and in many cases will require close cooperation with educational institutions and online education providers. Most institutional and governmental financial support for higher education is aimed at young people; far fewer financing options are available for those looking to upgrade skills, especially if they do not work for a large employer willing to finance some or all of their training. Federal Pell Grants, for example, which are the largest source of federal aid for lower-income students, are not available for those pursuing short-term career-oriented certificates through community colleges and other educational providers.

Some large companies have been pioneering new approaches. AT&T employs some 280,000 people, and their jobs have been transformed over the past two decades as the company has acquired and built out massive wireless networks. That has required employees to develop new skills in cloud-based computing, coding, and other technical capabilities; as one company executive put it, most of the company’s employees “signed up for a deal that is entirely different from the environment in which their business operates today.”91 Over the past four years, the company has spent $250 million on employee education, and 140,000 employees have signed up to retrain for the new roles, which they are expected to do on their own time. AT&T has experimented with new forms of education to help employees fit the training into their schedules—it has, for example, teamed up with Georgia Institute of Technology and Udacity to offer an online master’s degree in computer science, and Udacity has developed smaller micro-degrees for specialties including coding and web development. Other companies have launched similar initiatives. United Technologies, the parent company of engine maker Pratt and Whitney, has for two decades offered tuition reimbursement of up to $12,000 for employees to pursue part-time degrees.92

Retailers, many of which are facing problems with job retention, have launched their own initiatives to challenge the negative perception of retail jobs as dead-end jobs with little possibility for advancement or lateral moves. Costco helps employees who want to rise to management positions return to school to acquire the credentials to move up in the company.93 Walmart, the nation’s largest private employer, with a U.S. workforce of more than 1.3 million, has launched a new wage and training initiative at a cost of nearly $3 billion. Since early 2016, nearly four hundred thousand junior employees have gone through a program called Pathways, which focuses on basic business and math skills, as well as soft skills such as interviewing and interacting with customers. Employees who complete the short program receive a one-dollar-per-hour raise. Additionally, more than 250,000 mid-level managers have graduated from Walmart Academies, which teach advanced retail skills, leadership skills, and specifics of how to run individual store departments.94 Amazon’s Career Choice Program pays up to 95 percent of tuition costs, to a maximum of $2,000, for warehouse employees who have been with the company at least three years and want to learn unrelated skills such as computer-aided design or medical lab technologies.95 A study by the National Skills Coalition found that 60 percent of retail workers are not proficient in reading and 70 percent have difficulty working with numbers.96 Several studies have looked at the potential career gains that entry-level retail employees can make from such education and training initiatives at the workplace, and at the value to companies in greater employee retention and improved customer experience.97 To achieve their real promise, such training initiatives will need to be increasingly collaborative across sectors and employers. The skills developed in retail, for example, could allow employees to make lateral moves into sectors requiring similar skills, such as hospitality and food service.

60 percent of retail workers are not proficient in reading and 70 percent have difficulty working with numbers.

While such initiatives can and should be embraced by more companies, it is harder for smaller firms to support this sort of retraining. It should be easier for smaller companies to interact with local workforce development boards, community colleges, and even universities to discuss their workforce needs and ways the institutions might be able to help.

Some governments have gone further in trying to expand lifelong-learning opportunities to more of their citizens. Singapore, which has the advantage of being a small country with a population of less than six million, launched its SkillsFuture initiative in 2015, which offers an educational credit for all Singaporeans to return to school if they wish. Singapore also does in-depth analyses of the skills needs of its workforce and tries to target training to meet those needs. The government argues that “with the fast pace of technological advancements and stronger global competition for jobs, skills upgrading and deepening are essential for Singaporeans to maintain a competitive edge.”98 If a U.S. state followed Singapore’s model, it would likely become a leader in attracting new investment and retaining jobs.

U.S. efforts to help workers make the transition from one job or career to another are inadequate. Unemployment insurance is too rigid and covers a fraction of the eligible workforce, and retraining programs such as Trade Adjustment Assistance are not based on the best global models.

In an ideal, full-employment labor market, most job changes would be voluntary, and the period of unemployment would be brief. But policymakers have long understood that the cyclical nature of modern economies often makes full employment an elusive goal. At any given time, millions of people are likely to be out of jobs involuntarily and looking for work, and in times of recession and economic slowdown, those numbers will spike.

In the United States, most of those workers are on their own. The U.S. unemployment insurance (UI) system, which provides temporary income support for individuals after they lose their jobs, was only ever intended to offer some short-term income support while employees moved from one job to the next. The generosity of benefits varies widely from state to state but is generally modest.99 Many are excluded because they cannot prove they were laid off without cause, or they have simply been out of a job for too long and their benefits have expired. Those employed as independent contractors or working in the gig economy of on-demand work are similarly excluded from UI benefits. The percentage of unemployed workers who are able to collect UI benefits has fallen from half of all workers in the 1950s to just over one-quarter today.100 Unemployment insurance no longer serves even the modest function of cushioning income losses for those who are temporarily without work through no fault of their own.

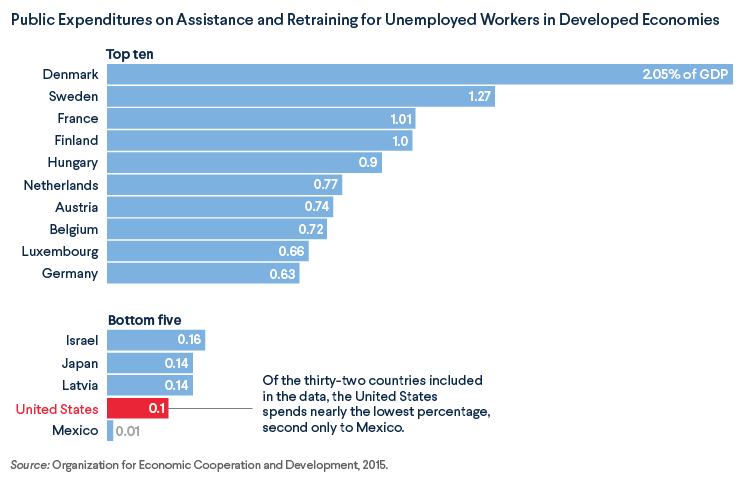

U.S. programs to assist with job transitions have long been recognized as inadequate. In part because the United States generally had much higher levels of labor force participation than most countries in Europe, U.S. policy has put the onus on workers to find new employment with little outside assistance.101 But U.S. labor participation rates plummeted during the Great Recession and have not fully recovered. According to the OECD, the U.S. employment rate of 72.6 percent is now roughly at the European Union average, and considerably lower than that of the United Kingdom and Germany (77.6 percent) and Canada (78 percent).102 U.S. government support for retraining for the unemployed is a fraction of that in most other advanced economies: the United States spends roughly one-fifth of what the average European country spends on active labor market programs, which are designed to provide individuals who lose their jobs with the training, skills, and job counseling they need to return to the job market.103

The standard program for unemployed workers, the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) of 1998 (updated and renamed by Congress in 2014 as the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act [WIOA]), provides minimal assistance for displaced workers. Most are eligible for basic skills assessments and job search assistance, and some get more in-depth job counseling and individualized assistance. Under WIA, those services had to be exhausted before workers were eligible for any sort of education or training that might improve their prospects of finding a better job, and only roughly 5 percent qualified.104 The system under WIOA is less rigid and some unemployed people can enter retraining more quickly, but federal funding for retraining dislocated workers has been flat, and funding for basic adult education has declined and is likely to face further cuts.105 More generous support for retraining is available under the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program for the small number of workers—fifty-five thousand recipients in fiscal year 2016—who can show that they lost their jobs to import competition or outsourcing. But even TAA falls short: the retraining programs too often do not align with local labor market needs, and the subsidy for workers who wish to move to find employment is capped at a mere $1,500, far too small to make a difference. And with more job loss now caused by new technology than by trade competition, having a transition program devoted solely to trade-displaced workers, rather than a broader effort to help displaced workers, makes little sense.106

Some U.S. policies have effectively discouraged retraining and reemployment. In communities that were hit hardest by import competition from China in the 2000s, for example, there was a huge increase in the number of workers applying for and receiving Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). The costs to taxpayers for SSDI were thirty times as large as expenditures for TAA. And unlike TAA, which is a temporary program, SSDI payments are usually permanent.107 Under SSDI, workers who show they are unable to return to work for some medical reason are eligible to collect Social Security payments, often for the remainder of their lives. SSDI raises the likelihood of abuse of legally prescribed drugs, because those with ailments may be prescribed opioid-based painkillers whose costs are covered under Medicaid.108 Drug use then becomes a further hurdle to returning to the job market. Some 4 percent of working-age Americans have already left the workforce through SSDI and related programs.

There are many successful models from elsewhere in the world that have shown success in retraining and quickly moving workers back into the job market. Sweden, for example, has set up Job Security Councils (JSCs) across the country. These are nonprofit organizations run by a board of representatives split equally between employers and employees, financed by a small contribution from employers. The goal of the JSCs is to encourage as seamless a transition as possible for laid-off workers. Employers are required to give significant advance notice of layoffs, and the JSCs then work to provide counseling and guidance—and, if necessary, retraining or business start-up support—to those who are facing job loss. Over 85 percent of Swedish workers are reemployed within a year, the highest percentage in any OECD country.109 Denmark has a similarly successful system that combines a flexible labor market with relatively low levels of job security (similar to the United States) and generous access to training and reemployment services to help workers get back on their feet.110

The U.S. economy would see collateral benefits from stronger transition assistance. In its 2017 employment report, which looks at responses from all the advanced economies, the OECD argues that increased spending on active labor market programs—including job search assistance, wage subsidies, and training—is especially effective at reducing unemployment during economic downturns like the one the United States experienced following the 2008 financial crisis.111

Too many jobs are going unfilled because of restrictions related to credentialing, mobility, and hiring practices. More could also be done to help businesses expand and to create new opportunities in higher-unemployment regions.

There are nearly six million job openings in the United States, close to the largest number since the Department of Labor began tracking in 2000. Seven million workers are officially unemployed, and millions of others either are underemployed or have dropped out of the labor market entirely.112 Many of the challenges of today’s workforce concern education, training, and skills, as discussed above. In other cases, employers say they are having difficulty finding employees who can pass drug tests and demonstrate reliable work habits; earlier exposure to the requirements of the workplace in the form of internships that require young people to show up on time and maintain a professional demeanor could help in this regard. But there are also significant “matching” problems—employees who could do the jobs that are open are not in the right places, have earned credentials that are not recognized, or are not being hired even though they have the right capabilities for the job. Broadly speaking, there are three types of matching issues: mobility, occupational licensing, and the hiring process.

Americans used to be among the most mobile people in the world. In 1948, when the Census Bureau began tracking how many Americans move from one place to another each year, it found that more than 20 percent of the country had relocated in the previous year. Those numbers began to fall in the 1980s and 1990s, and then dropped steeply after 2000. Americans relocate in search of new work and career opportunities much less than they once did.113 That declining mobility appears to be a significant part of why the gap between the richer and poorer states stopped closing in about 1980. For a century prior to that, Americans would move from poorer regions to the wealthier states and cities where jobs were being created, which had the effect of both dampening wage growth in the richer regions and boosting it in the poorer ones.114

Declining mobility is a big problem because job growth has become increasingly concentrated. The fastest growth in the country has taken place in the big cities, often those with strong technology economies, such as Boston, Denver, New York, San Francisco, and Seattle, and in energy-strong regions including the Dakotas and Texas.115 Cities that already have a high concentration of highly skilled jobs are also attracting most of the new highly skilled jobs.116 The gap between larger cities and smaller ones has been growing, with many smaller cities struggling to recover from the decline in manufacturing employment.117

The reasons for the steep decline in mobility are not entirely clear, but there are several likely culprits. Housing prices are clearly a barrier in the largest cities and are exacerbated by land-use restrictions primarily under the control of regional and municipal governments, which impose far more restrictions on housing construction than they once did.118 While the motivations behind zoning restrictions—to create more livable neighborhoods—are laudable, in the absence of other mitigating policies they have helped drive housing prices into the stratosphere in cities that have seen strong job growth, including Denver, Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle. An absence of affordable housing prevents workers from relocating from lower-productivity regions to higher-productivity regions, which creates significant losses to the U.S. economy.119 Federal government subsidies for low-income housing have also been shrinking.120 Transportation infrastructure is another problem. Many job opportunities could be opened up if commuting times were reduced from the outer rings of the large cities, where housing costs are lower; since 2000, a growing number of Americans have found themselves living in towns or suburbs that are beyond the commuting reach of most jobs. The decline in proximity to jobs has been particularly steep for Latinos and African Americans.121 Overcoming this barrier will require greater investments in all forms of transit, especially mass transit.

Occupational licensing—most of which is, again, under the authority of state and local governments—is also a significant obstacle that prevents Americans from moving for better work opportunities. The country’s three million teachers, for example, need state-issued licenses in order to work in public schools, and in many private schools as well. States often have quite different requirements for obtaining and maintaining teaching credentials, and reciprocity is limited; most teachers who move from one state to another have to meet some additional educational requirement to obtain a certificate.122 One study of the Pacific Northwest suggested that licensing restrictions meant that teachers near the Oregon border in Washington State were three times as likely to move to another teaching job somewhere else in Washington rather than make the much shorter move across the border to teach in Oregon.123 Many other occupations—including bartender, interior decorator, cosmetologist, manicurist, and florist—typically require some sort of state licensing that is not generally recognized in other states. Roughly 25 percent of workers today require some sort of state license, compared with just 5 percent in the 1950s.124 While such credentialing is often necessary to protect consumer health and safety or ensure the high qualifications of individuals doing the work, too often the requirements serve as unreasonable barriers to entry, and the lack of cross-state cooperation in recognizing these credentials is a major obstacle to mobility.125

Finally, the hiring process does not function as well as it needs to. Too many college-educated young people are being hired for jobs that do not require four-year degrees; a 2014 Federal Reserve study found that more than 40 percent of recent college graduates were hired for jobs that have not traditionally required a college degree, a figure that has been rising since 2001.126 Applicant tracking systems, which are widely used by employers to handle the enormous volume of online job applications, are often set up to weed out applicants without college degrees.127 A Burning Glass study found that 65 percent of current postings for executive secretaries and executive assistants list a bachelor’s degree as a requirement, even though just 19 percent of people currently doing those jobs have four-year degrees.128 Harvard Business School argues that “degree inflation”—in which employers demand four-year degrees for jobs that did not previously require them—“is a substantive and widespread phenomenon that is making the U.S. labor market more inefficient.”129 Americans are excluded from jobs for which they are qualified, and college graduates are underemployed. The effects are particularly negative on populations that have lower-than-average college graduation rates, such as African Americans and Latinos.

Development of industry-wide credentials could help in this regard, as would more active corporate initiatives to develop their own workforce pipelines. But new hiring practices are also needed to help match employees’ skills to employers’ needs. New digital platforms could do a great deal to solve the matching problem. With platforms such as LinkedIn, job seekers can now search potential openings across the country, and employers have new tools to locate, identify, and screen potential candidates. Such platforms may also facilitate part-time and gig occupations, opening opportunities for those unable or unwilling to pursue traditional full-time employment.130

Nongovernmental initiatives such as Skills for Chicagoland’s Future and Skills for Rhode Island’s Future have demonstrated the benefits of active counseling to match employers with qualified individuals who are unemployed or underemployed.131 The initiative has been especially focused on the problem of youth unemployment. A 2017 evaluation of the programs showed significant benefits above and beyond the job placement services that WIOA provides.132 Opportunity@Work is another initiative aimed at expanding tech training and work opportunities to groups that face significant employment barriers, including veterans, people with disabilities, people with limited English proficiency, and those with criminal records.133 Opportunity@Work, with support from the Department of Labor, is working closely in seventy-two technology communities around the country with employers such as Dell, local workforce development boards, and community colleges to open doors for those who have acquired relevant skills but lack a four-year degree or long work experience that would make them obvious candidates for employers.

Local, state, and federal governments’ existing policies to support work are outdated for the new economy. Current workplace benefits—from sick leave to retirement plans—are too often available only to workers with full-time jobs and are not adapted to the emerging world in which more workers are part-time, contract, or gig workers.

Meeting the growing demand for jobs that require higher levels of education and skills needs to be a priority, but many of the jobs that are and will be created are not traditional, full-time occupations working for a single employer. Workers in alternative arrangements—including independent contractors, freelancers, temporary employees, and gig economy workers—now make up some 16 percent of the total U.S. workforce, a figure that has grown by half over the last decade.134 Nearly all the net employment growth from 2005 to 2015 came from contingent work.135 More than 7.5 million workers, most of them low income, hold more than one job. Some of these workers find themselves in precarious “just-in-time” arrangements. Not all of this workforce, by any stretch, is doing such jobs as a last resort. Some may hold part-time positions to supplement their incomes; others, such as young parents, may prefer the flexibility of part-time or gig work. Many Americans no doubt value the flexibility that comes from being able to earn some extra cash by renting out a room through Airbnb or driving for Uber or Lyft. The 2017 tax bill passed by Congress is likely to accelerate the growth of contingent work by providing significant tax savings to independent contractors and freelance workers that are not available to salaried employees.136

The growth of both the part-time and contingent workforce, however, points to a huge challenge for the future of the U.S. workforce—the large and growing holes in the support systems for working individuals and families. Since the 1940s, health insurance for American workers has been largely provided by employers and available primarily for full-time employees, as are other benefits including sick leave, family leave, overtime pay, and paid vacations.137 Retirement benefits are also normally tied to traditional jobs. Contingent and part-time workers are generally not offered company training programs, tuition reimbursement, or loan repayment assistance. Those outside the traditional workforce find themselves in a kind of black hole where they are ineligible for many taxpayer-supported programs that are designed to protect Americans on the job and in retirement, and they have limited prospects for career advancement.

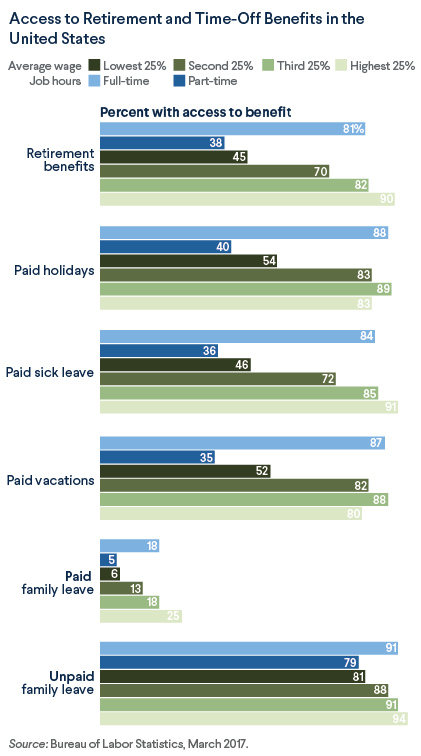

Only two-thirds of private-sector workers, for example, have access to any sort of retirement benefits through their jobs; among the lowest-paid workers, only one-third have such access, and only 14 percent are participating in those plans.138 Other workplace benefits—including paid sick leave and paid vacation days—are similarly skewed in favor of higher-income workers with full-time jobs. Eighty-four percent of full-time workers are eligible for paid sick leave, for example, but only 36 percent of part-time workers are. Similarly, 92 percent of workers earning in the highest bracket (the top 10 percent) are guaranteed sick leave, but only 31 percent of the lower earners enjoy the same benefit.139 The United States has especially weak protections for temporary workers compared to other advanced economies, many of which require equal pay rates and the same benefits that are available to full-time employees.140

Many of these part-time workers live precarious lives. The most recent study of household economic well-being by the U.S. Federal Reserve found that 30 percent of adults—or seventy-three million Americans—say they are barely getting by financially; among those with a high school degree or less, the figure was 40 percent. Nearly 30 percent of adults say they earn money through “informal” methods to supplement their paid employment. And 44 percent said they would not be able to cover an emergency expense of $400, or would be forced to borrow money or sell something to do so.141 Many Americans also experience great volatility in their monthly incomes.142

The federal and state governments administer a variety of programs that are intended to supplement the incomes of lower-wage workers, including food stamps, Medicaid, and public housing or rent assistance. Many of these programs do help provide an important cushion for low-wage workers. But these are essentially a social-service model, designed to help what is seen as a vulnerable population. The programs should be supplemented by ensuring that the sorts of benefits that better-paid, full-time workers take for granted are similarly available to lower-income, part-time, and contingent workers.

The most urgent need is to expand employment benefits for those who are in nontraditional or part-time work arrangements. The segmentation between full-time work on the one hand and part-time work and independent contracting on the other, in terms of labor market regulations, also encourages some companies to expand the use of contingent workers, in part to avoid the cost of benefits associated with full-time work. If workers were eligible for benefits on a prorated basis, that incentive would be reduced or eliminated. Some states have been considering efforts to implement new systems in which, for example, part-time workers would earn vacation and sick days from one or more employers, which could then be used as needed.143 New York State has also launched a task force to develop options and recommendations for increasing the portability of benefits.144 In its recent review of employment policies, the OECD argued that portability should be the model for all advanced economies in the twenty-first century.145

The purpose of portable benefits is not just to improve the lives of workers, though that should, of course, be a paramount goal. Initiatives that improve the working conditions for many are also likely to have broader economic payoffs as well. More economically secure workers are more likely to invest, spend, and boost economic demand, the lack of which has been a primary cause of weak economic growth. Individuals might also feel safer in taking the risk of starting new companies if they were confident they had more secure benefits. The labor legislation of the 1930s, which established a national minimum wage, prohibited child labor, created national unemployment and retirement insurance, implemented the forty-hour workweek, and required overtime pay for many workers, is credited by economic historians with helping to lay stronger foundations for the long prosperity that followed.146 New initiatives to meet the labor market challenges of the twenty-first century are long overdue.

Addressing the twin challenges of creating better working opportunities and ensuring competitive success in a global economy reshaped by technology and trade is not just a domestic economic and social challenge for the United States—it is a national security priority. The challenges outlined above influence the United States' ability to act effectively and lead on the world stage. In the face of competing political and economic models, a United States that offers successful paths to opportunity and prosperity for its citizens demonstrates the gains that come from liberal democracy and open markets. In the twenty-first century, the United States should once again lead by example in building the most productive, inclusive, and resilient economy in the world. Building the workforce of the future needs to become an urgent priority, not just in Washington but at all levels of government and across American society.