UN Climate Talks

1992 – 2025

Since 1992, when the United Nations recognized climate change as a serious issue, negotiations among countries have produced notable accords, including the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement. But leaders have struggled to maintain momentum and failed to slow global temperature rise.

By experts and staff

- Updated

By

- Lindsay MaizlandSenior Writer/Editor, Asia

- Clara FongWriter/Editor, Asia

1992

Groundbreaking Rio Earth Summit

The summit results in some of the first international agreements on climate change, which become the foundation for future accords. Among them is the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) [PDF], which aims to prevent “dangerous” human interference in the climate system, acknowledges that human activities contribute to climate change, and recognizes climate change as an issue of global concern. The UNFCCC, which went into force in 1994, does not legally bind signatories to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and gives no targets or timetables for doing so. But it requires frequent meetings between the ratifying countries, known as the Conference of the Parties, or COP. As of 2019, it has been ratified by 197 countries, including the United States.

1995

First Meeting of UNFCCC Signatories

UNFCCC signatories gather for the first Conference of the Parties, or COP1, in Berlin. The United States pushes back against legally binding targets and timetables, but it joins other parties in agreeing to negotiations to strengthen commitments on limiting greenhouse gases. The concluding document, known as the Berlin Mandate [PDF], lays the groundwork for what becomes the Kyoto Protocol, but it is criticized by environmental activists as a political solution that does not prompt immediate action.

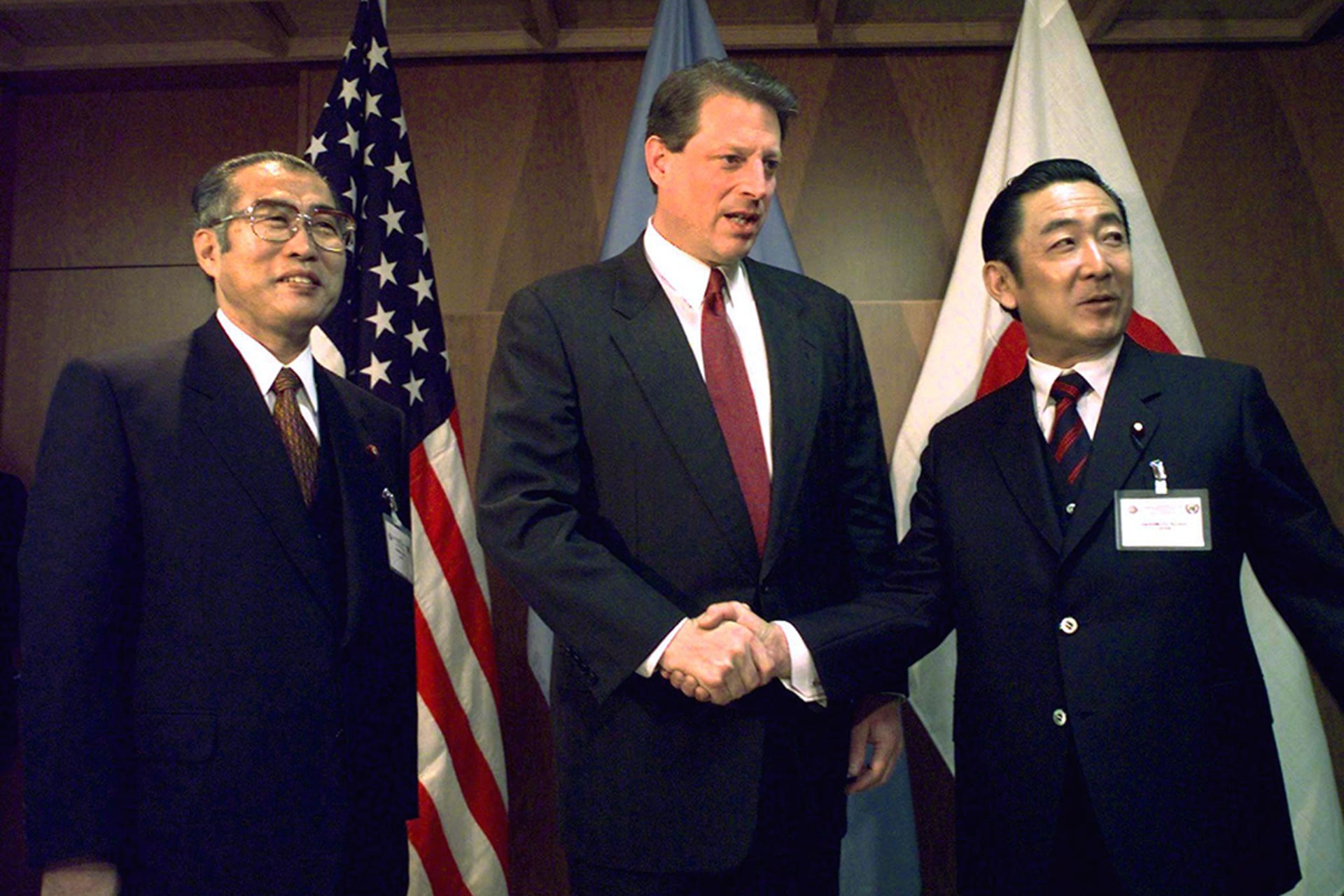

1997

In Kyoto, First Legally Binding Climate Treaty

At COP3 in Japan, the conference adopts the Kyoto Protocol [PDF]. The legally binding treaty requires developed countries to reduce emissions by an average of 5 percent below 1990 levels and establishes a system to monitor countries’ progress. But the protocol does not compel developing countries, including high carbon emitters China and India, to take action. It also creates a carbon market for countries to trade emissions units and encourage sustainable development, a system known as “cap and trade.” Countries must now work out the details of implementing and ratifying the protocol.

2001

Breakthrough in Bonn, But Without the U.S.

The Kyoto Protocol is in jeopardy after talks collapse in November 2000 and the United States withdraws in March 2001, with Washington saying that the protocol is not in the country’s “economic best interest.” In July 2001, negotiators in Bonn, Germany, reach breakthroughs on green technology, agreements on emissions trading, and compromises on how to account for carbon sinks (natural reservoirs that take in more carbon than they release). In October, countries agree on the rules for meeting targets set by the Kyoto Protocol, paving the way for its entry into force.

2005

Kyoto Protocol Takes Effect

The Kyoto Protocol enters into force in February after it is ratified by enough countries to account for at least 55 percent of global emissions. Notably, it does not include the United States, the world’s leading carbon emitter. Between 2008 and 2012, when the protocol is set to expire, countries are supposed to reduce emissions by their pledged amounts: The European Union commits to reduce emissions by 8 percent below 1990 levels, Japan commits to 5 percent, and Russia commits to keeping levels steady with 1990 levels.

2007

Negotiations Begin for Kyoto 2.0

Before COP13 in Bali, Indonesia, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) releases a new report with its strongest language yet confirming that global warming is “most likely” caused by human activity. During the conference, discussions begin on a stronger successor to the Kyoto Protocol. But they come to a standstill after the United States objects to a widely backed proposal that calls for all industrialized nations to cut greenhouse gas emissions by specific targets. U.S. officials argue that developing countries must also make commitments. A delegate from Papua New Guinea tells the United States to “get out of the way” if it does not want to lead the international response to climate change. Washington eventually backs down, and the parties adopt the Bali Action Plan, which establishes the goal of drafting a new climate agreement by 2009.

2009

September 2009

U.S. Joins Bold Statements at UN

Three months ahead of the target date for a new agreement, several world leaders pledge actions during a UN summit on climate change hosted by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. Chinese President Hu Jintao announces a plan to cut emissions by a “notable margin” by 2020, marking the first time Beijing commits to reducing its rate of greenhouse gas emissions. Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama pledges to reduce emissions by 25 percent. U.S. President Barack Obama, in his first UN address, says the United States is determined to act and lead, but he doesn’t offer any new proposals. Ban expresses hope that leaders will reach a “substantive deal” during the upcoming conference in Copenhagen.

December 2009

Disappointment in Copenhagen

The successor to the Kyoto Protocol is supposed to be finalized at COP15 in Copenhagen, but the parties only come up with a nonbinding document that is “taken note of,” not adopted. The Copenhagen Accord [PDF] acknowledges that global temperatures should not increase by 2°C (3.6°F) above preindustrial levels, though representatives from developing countries sought a target of 1.5°C (2.7°F). (A 2009 report from the American Meteorological Society predicts a 3.5°C [6.3°F] to 7.4°C [13.3°F] increase in less than one hundred years). After leading the negotiations, U.S. President Barack Obama tells the conference that the accord is “not enough.” Some countries later vow to follow the accord—though it remains nonbinding—and make their own pledges.

2010

Temperature Target Set in Cancun

There is increased pressure to reach a consensus in Mexico during COP16 after the failure in Copenhagen and NASA’s announcement that 2000–2009 was the warmest decade ever recorded. Countries commit for the first time to keep global temperature increases below 2°C in the Cancun Agreements. Approximately eighty countries, including China, India, and the United States, as well as the European Union, submit emissions reduction targets and actions, and they agree on stronger mechanisms for monitoring progress. But analysts say it’s not enough to stay below the 2° target. The Green Climate Fund, a $100 billion fund to assist developing countries in mitigating and adapting to climate change, is also established. As of 2019, only around $3 billion has been contributed.

2011

New Accord to Apply to All Countries

The conference in Durban, South Africa, nearly collapses after the world’s three biggest polluters—China, India, and the United States—reject an accord proposed by the European Union. But they eventually agree to work toward drafting a new, legally binding agreement in 2015 at the latest. The new agreement will differ from the Kyoto Protocol in that it will apply to both developed and developing countries. With the Kyoto Protocol set to expire in a few months, the parties agree to extend it until 2017.

2012

No Deal in Doha

Negotiators in Doha for COP18 extend the Kyoto Protocol until 2020, but remaining participants account for just 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. By this time, Canada has withdrawn from the treaty, and Japan and Russia say they will not accept new commitments. (The United States never signed on.) Environmental groups criticize countries for not reaching an effective agreement as Typhoon Bopha slams the Philippines, which they say exemplifies a rise in extreme weather caused by climate change. One of the conference’s successes is the Doha Amendment, under which developed countries agree to assist developing countries mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change. The agreement also sets delegates on the path toward a new treaty.

2013

Walkout in Warsaw

During the first week of COP19 in Poland, a grouping of developing countries, known as the Group of Seventy-Seven (G77), and China propose a new funding mechanism to help vulnerable countries deal with “loss and damage” caused by climate change. Developed countries oppose the mechanism, so the G77’s lead negotiators walk out of the conference. Talks eventually resume, and governments agree to a mechanism [PDF] that falls short of what developing countries wanted. Countries also agree on how to implement an initiative to end deforestation known as REDD+, but the conference is described by analysts as the “least consequential COP in several years” [PDF].

2015

Landmark Paris Agreement Reached

One hundred ninety-six countries agree to what experts call the most significant global climate agreement in history, known as the Paris Agreement. Unlike past accords, it requires nearly all countries—both developed and developing—to set emissions reduction goals. However, countries can choose their own targets and there are no enforcement mechanisms to ensure they meet them. Under the agreement, countries are supposed to submit targets known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). The mission of the Paris Agreement, which enters into force in November 2016, is to keep global temperature rise below 2°C and pursue efforts to keep it below 1.5°C. But analysts urge more action to achieve this goal. In 2017, President Donald J. Trump withdraws the United States from the agreement, saying that it imposes “draconian financial and economic burdens” on the country.

2018

Rules for Paris Agreement Decided

Just ahead of COP24 in Katowice, Poland, a new IPCC report warns of devastating consequences—including stronger storms and dangerous heat waves—if the average global temperature rises 1.5°C above preindustrial levels and projects that it could reach that level by 2030. Despite the report, countries do not agree to stronger targets. They do, however, largely settle on the rules for implementing the Paris accord, covering questions including how countries should report their emissions. They do not agree on rules for carbon trading, however, and push that discussion to 2019.

2019

September 2019

UN Chief Plans Climate Action Summit

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres organizes the UN Climate Action Summit for world leaders in New York. Countries are mandated by the Paris Agreement to submit revised NDCs by the following year, so the meeting is a chance for leaders to share their ideas. But leaders of the world’s top carbon-emitting countries, including the United States and China, do not attend. At the summit, Guterres asks countries to submit plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 45 percent by 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2050.

December 2019

Lost Opportunity in Madrid

COP25 is marked by a lack of progress on major climate issues despite a year of dire warnings from scientists, record heatwaves, and worldwide protests demanding action. Negotiators are unable to finalize rules for a global carbon market, and they disagree over whether to compensate developing countries devastated by effects of climate change including rising sea levels and extreme weather. The conference’s final declaration does not explicitly call on countries to increase their climate pledges made under the Paris Agreement, and Secretary-General Guterres describes the talks as a lost opportunity.

2020

April 2020

Talks Postponed Amid COVID-19 Pandemic

The United Nations postpones COP26, originally scheduled for November 2020, until 2021 because of a pandemic of a new coronavirus disease, known as COVID-19. Countries were expected to strengthen their emissions reduction goals set under the Paris Agreement at the conference in Glasgow. Amid the pandemic, emissions fall worldwide as many countries implement nationwide shutdowns that drastically slow economic activity. But experts predict that the reductions won’t last, with governments under pressure to boost output and disregard the environment to save their struggling economies.

2021

July 2021

Nations Update Pledges Ahead of COP26

More than one hundred countries, altogether accounting for nearly 60 percent of Paris Agreement signatories, meet the deadline to submit updated NDCs ahead of COP26 in November. Some of the top emitters propose more ambitious targets. President Joe Biden announces that the United States will aim to cut its emissions to roughly half of its 2005 level by 2030, doubling President Obama’s commitment. Meanwhile, China and India, responsible for roughly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, miss the deadline. An IPCC report [PDF] released the following month predicts that the world will reach or exceed 1.5°C of warming within the next two decades even if nations drastically cut emissions immediately.

November 2021

1.5°C Goal ‘Kept Alive’ in Glasgow

COP26 President Alok Sharma says commitments made during the conference keep the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C “alive” but its “pulse is weak.” The final agreement, the Glasgow Climate Pact, calls for countries to reduce coal use and fossil fuel subsidies—both firsts for a UN climate agreement—and urges governments to submit more ambitious emissions-reduction targets by the end of 2022. In addition, delegates finally establish rules for a global carbon market. Smaller groups of countries make notable side deals on deforestation, methane emissions, coal, and more. But analysts note that even if countries follow through on their pledges for 2030 and beyond, the world’s average temperature will still rise 2.1°C (3.8°F).

2022

November 2022

Breakthrough on Loss and Damage but Little Else in Egypt

At COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, nations agree [PDF] for the first time to establish a fund to compensate poor and vulnerable countries for losses and damages due to climate change, though the details are left undecided. Also for the first time, the conference’s final communiqué calls for global financial institutions to revamp their practices to address the climate crisis. However, countries don’t commit to phasing down use of all fossil fuels, and a goal to reach peak emissions by 2025 is removed from the communiqué. Guterres says that continuing to use fossil fuels means “double trouble” for the planet.

2023

September 2023

UN Releases Technical Findings From the First Global Stocktake

Conducted every five years, the global stocktake assesses countries’ progress toward implementing the Paris Agreement. Over the course of two years, countries submit their information to the UN, which evaluates their efforts to cut emissions and adapt to climate disasters. The technical report concludes the world is still “not on track” to meet the goals set out during the Paris Agreement, but current policies have curbed the worst-case scenario of 3.7°C to 4.8°C (6.7°F to 8.6°F) of warming by 2100. Expected temperature increases now range between 2.4°C to 2.6°C (4.3°F to 4.6°F), with the possibility of dropping to as low as 1.7°C to 2.1°C (3.1°F to 3.8°F) if countries fully implement net-zero emissions targets.

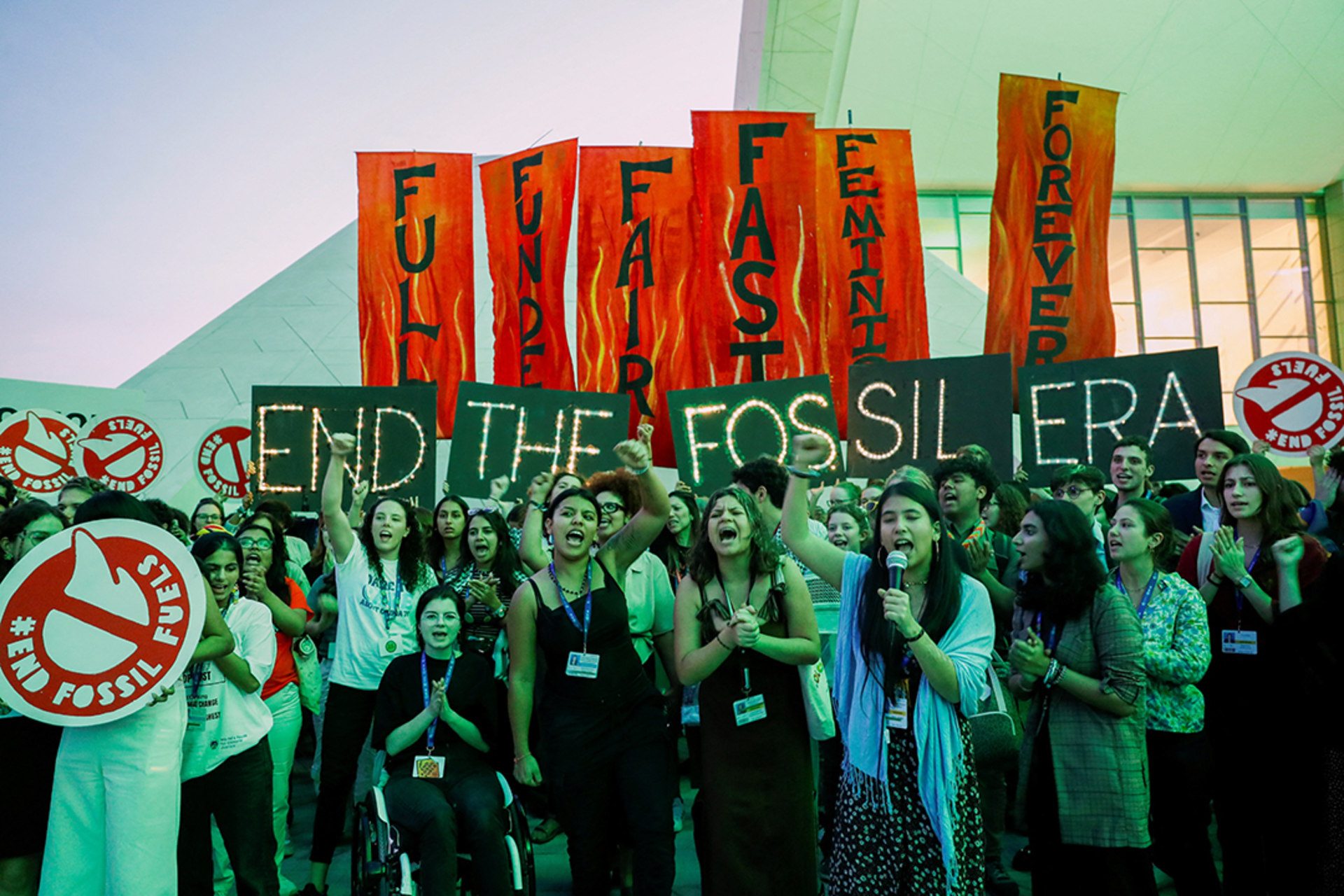

December 2023

Nations Reach Milestone Deal to Transition Away From Fossil Fuels

Countries agree to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels in a “just, orderly, and equitable manner” at COP28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The deal is the first time a UN climate agreement has explicitly mentioned a phase-down of fossil fuels. Among other provisions, the agreement calls [PDF] for tripling renewable energy capacity and slashing methane emissions by 2030, and hashes out the details of the Loss and Damage Fund agreed upon at the previous year’s conference. But according to a statement released by the Alliance of Small Island States, the deal falls short by not including language to formally “phase out” fossil fuels and leaving a “litany of loopholes” for ineffective carbon capture and storage and nuclear solutions. Still, UN Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell claims this agreement marks “the beginning of the end” of the fossil fuel era.

2024

November 11 – 22, 2024

In Azerbaijan, Disappointment on Finance Commitments

The final climate finance text agreed upon at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, calls on countries to mobilize at least $300 billion annually by 2035 for developing countries following another year of record-breaking extreme weather and destructive climate events. The agreement also sets a goal to scale up public and private financing to $1.3 trillion annually over the next decade. Experts say the new commitments still fall well below the funding needed by 2030 to meet global climate targets, estimated to be more than $6 trillion a year. Several countries and observers are also concerned by the final text lacking an explicit reference to fossil fuels, which some leaders argued is a step back from the previous year’s summit in Dubai. COP29 is the second consecutive year that a petrostate hosted the UN climate summit.

2025

November 10 – 21, 2025

Despite Some Agreement in Overtime, No Progress on Fossil Fuels in Belém

Marking the tenth anniversary of the Paris Agreement, COP30 in Belém, Brazil, goes into overtime to reach an agreement amid a strained multilateral atmosphere and the absence of the United States. Countries agree to triple adaptation finance by 2035, adopt a voluntary set of adaptation indicators, and deliver a just transition mechanism. However, roadmaps to phase out fossil fuels and combat deforestation proves too divisive, forcing the COP presidency to shift these topics to separate items outside the final text—which makes no mention of fossil fuels for a second year in a row. By the summit’s conclusion, 122 of 195 parties submit new or updated NDCs, but these commitments still fall short of curbing global warming to below the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target. Attending countries also reach a compromise on the host of COP31: the summit will take place in Antalya, Turkey, with Australia acting as the COP president.