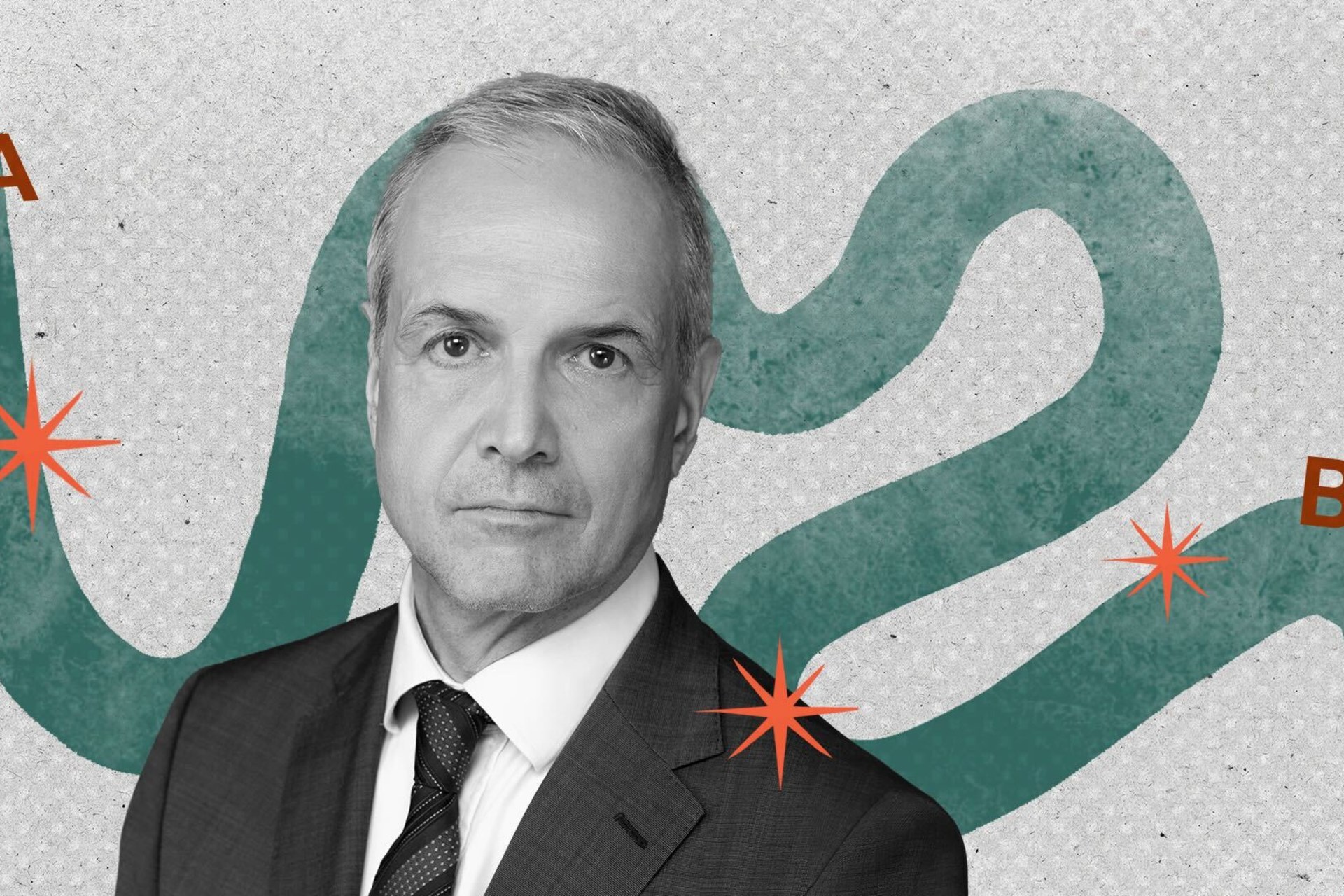

How I Got My Career in Foreign Policy: Michael Werz

Building on a wide-ranging career in academia and think tanks, Michael Werz is the senior advisor for North America and multilateral affairs to the Munich Security Conference. He sat down with CFR to discuss his interest in studying changing societies and the uniqueness of Washington, DC’s political culture.

Michael Werz began his career in academia, and his foreign policy work has been shaped by his training as a philosopher and intellectual historian. After his wife’s career brought them to the United States, Werz entered the think tank world of Washington, DC, where he has studied rapidly changing societies around the world. Currently, he’s a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations as well as a senior advisor for North America and multilateral affairs to the Munich Security Conference. Read more about Werz’s thoughts on the diminishing ambition in academia, the uniqueness of American think tank culture, and the particular allure of the “Seven Sisters” region of India.

Here’s how Michael Werz got his career in foreign policy.

What did you want to be when you were little?

That’s a good question. I think I had no clear notion. I grew up in a housing project, so there wasn’t much expectation. So nothing that I really vividly remember.

Where did you grow up?

In Germany, in an industrial town.

You started off in academia. Can you tell me a bit about your academic background?

I’m a philosopher and intellectual historian. I did my PhD in philosophy—which, in continental Europe, is different than here. As you probably know, philosophy here is mostly linguistic philosophy, logic. There is intellectual history, political economy, sometimes even social psychology, plus philosophical traditions in Europe—especially the particular philosophical tradition that I chose to focus on, which is the Frankfurt School of philosophy. So I went to Frankfurt to study that particular tradition. And I did my MA there, my PhD.

I was a tenured university professor when my wife got a job offer to run one of the German political foundations here in Washington, and that was the end of my academic career (laughs). I moved into policy just because there were no other jobs. That was very difficult at the time. We came here in 2003. I did some teaching as an adjunct at Georgetown University, but there were really, especially in my field of research, not many opportunities available here.

I got my first landing-pad job at the German Marshall Fund. That was how I got dragged into the lowly life of policy analysis and got stuck there. So it was nothing that was planned. We also just had planned to stay in the United States for three years, and then we got stuck here, twenty-two years and counting now. So none of that was either planned or thought out. But what I tried to do is bring intellectual curiosity from my philosophical and social theory background into the work I do.

I was never interested in becoming a country specialist, much less an expat that is working on his or her own country, which I think is a problem here in Washington and other think tank environments as well. And I was always interested in how societies change. So I focus a lot of work on these complex crisis scenarios, because they were just overlapping. I ran the Turkey program at the Center for American Progress for ten years. I worked a little bit on Mexico, India, and was affiliated with a think tank in Hong Kong because I’m interested in China. Countries that were undergoing massive transformations always interested me a lot.

You moved here, but you could have kept working on international matters. How did you come to focus on American foreign policy?

I’ve worked on the United States for some time. I wrote my second book on the parallel history of migration, the history of changing forms of ethnic self-consciousness, and the development of the humanities in the United States between 1890 and 1990. So it’s a kind of long view on one hundred years of social, historical, and intellectual development, because the interesting thing in the United States is that intellectual traditions here were codified by British, French and German traditions. And in the 1920s there’s a very peculiar phase where your cities grew—a lot of Poles, Jews, Russians, Irish, people from all parts of the Western world. The cities became very diverse. You have, for the first time, substantial migration by Blacks from the South and Latino immigration to a smaller degree. And in that time period between the 1920s and early ‘30s, there’s a massive process where educational theory, philosophy, and most of all, sociology emancipate themselves from the European traditions.

My hypothesis is that this occurs because of the ethnic diversity of the United States, because European societies were ethnically homogeneous, especially after all the Jews were kind of discriminated against and kind of clustered. European societies were seen mostly as two dimensional, or upper classes [and] lower classes, capitalists and workers—however you want to put this. The ethnic depth dimension becomes prominent in American cities for the first time in the 1920s. It kind of creates and establishes a completely unique American intellectual tradition. It also establishes basketball, American football, and all the sports that the United States invents. That was kind of my interest.

So your interests drove you to focus on the United States.

Yes, because it’s the only country where this happens, right? The big question always is, “why does Europe start wars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries along the lines of ethnic belonging and national identity?” And why is it when somebody says, “I’m an ethnic German,” that usually is the first step towards starting to kill others, whereas when somebody says, “I’m proud to be an American” in the 1920s, this is actually something that is an inclusive patriotism versus an exclusive nationalism in Europe.

That question always interested me, and I think it has to do with the specific form in which, in the early twentieth century, this urban environment was establishing itself. Kind of by extension, that gave me the intellectual instruments and the curiosity to look at what is happening in Turkey, India, and Mexico, because these societies develop along very similar dynamics, especially when it comes to urban-rural migration and modernization processes.

You focus on big ideas in your work. What is the difference between doing that within academia and doing that in the think tank world?

That’s a very good question, and it’s not as easy to answer as one would think. It has to do with the diminishing intellectual ambition in many academic environments, mostly driven by the United States, which I would call the professionalization of academic education. That kind of forces kids into universities far too early, because there’s no military service and no gap years and stuff, but also because university degrees are extremely scholarized. They’re extremely organized. They are now also in Europe, increasingly, because they’re following the Anglo-Saxon model. So I think big ideas are not really easy to develop in academia.

On top of that, you had—especially in the political sciences, I would argue—with the 1990s, early 2000s, with game theory, rational choice theory, a kind of dumbing down of the science of understanding society. It suggested that it was mostly about empirical research and numbers, and that you could predict fairly linear developments, and it took out the kind of dialectical dynamic that, in previous decades, were the access point.

Then on the policy side, if you have good ideas, especially in Washington, and if you understand the differentiated processes that are happening, you have good opportunities; but you’re also often surrounded by many people that are thinking about historical and political developments in a very linear fashion. Which I think—at least in part in the United States—has to do with the fact that the U.S. is the only country in the twentieth century that didn’t change its political system. It didn’t change the economic system. Didn’t change its flag. Not a single European country or Asian country survived the twentieth century without changing borders, changing flags, changing political systems, right?

I think it has to do with the fact also that there is a notion in the United States that things do not change as quickly and as substantially as they do, which is, I think, one of the reasons why, still, so many people here in Washington are completely underestimating what’s happening.

You mentioned that there’s diminishing ambition in academia, or it’s not fostering big ideas. Do you mean it’s about placing your work in publications, but they won’t accept the submissions?

I think it has to do with the academic division of labor; it’s a highly differentiated environment. With the craziness that, as a PhD student, you have to document a completely new piece of research, which means it gets smaller and smaller and smaller—and there’s so many PhDs in the United States, on top of that. Increasingly in continental Europe as well, it’s extremely driven by empirical research. Yes, it’s important, but it’s nothing that means that you have the intellectual ambition to understand broad processes of social transformation that are going on in society.

Then also with the more eclectic system, you basically have these established career paths where you need so many points and so many clusters and so many classes that you have to have—to do your BA and then your MA—and so I think it is basically standing in the way of qualitatively, understanding what is happening.

And many students, especially because this is so expensive, are so rushed that they legitimately don’t feel that they have the time to read stuff that’s not geared towards the seminars. In the United States, particularly, you have professors that are assigning 800 pages a week. Which is crazy—when I used to teach at Georgetown, I spent two weeks on Georg Simmel’s essay on the foreigner, which is seven pages long. You can teach an entire seminar on that, on those seven pages, because they are so densely written. I had students that said in the class, “Why are we not reading more?” They felt it was a waste of their time to really dig deep and understand one of the most interesting texts that has been written in the early twentieth century in German-language sociology. I think there’s just institutional barriers that are being erected.

I’m curious—another follow-up— about what you said in terms of the think tank world being so organized around linear thinking and how people are underestimating the sort of changes that are happening abroad. What do you think are the practical aspects of that? Less ambitious peace proposals?

No, I think part of the problem is that—it’s an advantage and a disadvantage—but you have a lot of people in the think tank world in Washington that have been in government or want to be. The U.S. system is interesting because it’s much more osmotic than other political systems, right? You have 4,300 people that rotate in and out of government if you have a change of the president in the White House. About 1,100 of them need Senate confirmation.

But that also means that when people come out of government and do research, they often look at the research questions kind of from the end point, because they are policy implementers. I have sometimes jokingly said, when I read policy papers, I have the impression that the policy recommendations were written and then the research that leads to those recommendations was done afterwards.

So I feel that there’s kind of a certain, again, linearity in the thought process— it’s completely understandable; for many policy issues, it’s important. But right now, for example, look at the cluelessness of many people in the business community that have a business school education, and realize that questions of very basic economic transformations—about trade, about how we deal with our society—are actually much more political than they thought, they just can’t be captured by numbers.

So again, the conversion of what used to be political economy in the early 1920s at the universities into a business school practical approach came with an advantage of incredible efficiency and at the price of a deep intellectual understanding of the political and social foundations of economic behavior.

I’m curious if you ever had the curiosity or the interest in working in the government or international institutions, like the United Nations? What part of that didn’t draw you?

No, never, because they’re very impatient, I hate bureaucracies, and also, I was never asked. Even if I wanted to do it—it’s very unlikely as an immigrant. National security stuff, it’s very difficult to get a job in, and in the United States especially, the government is so big that if you want a portfolio that’s interesting as a senior person, you need to have government and interagency experience to have that job. I came here too late, so to speak.

But I think institutions have a very singular dynamic of streamlining thought processes in a way that is outcome-oriented, and mostly—even when people say they are strategic—have a six- to twelve-month horizon, if you’re lucky. So they miss a lot of the longer, broader processes.

I think the mess that we’re in now with the Trump administration is Exhibit A: we’ve overlooked long-term, transformational processes in American politics and American society, in the public sphere, that we simply didn’t fully understand. So this is nothing that piqued my interest, because I was always more interested in the society part of transformations than in the political side.

But you are currently Senior Advisor for North America to the Munich Security Conference. What exactly does that mean? How did you get that job?

I got that job because the former chairman asked me. I didn’t ask for the job, the job asked me. I thought it was an interesting proposal, to contribute to the Munich Security Conference, which obviously is a very important platform.

Yeah, it’s one of the biggest conferences now. So what does a senior advisor do?

I mean, I can only speak to what I do. I had a very specific task of broadening the network of the Munich Security Conference, specifically among multilateral institutions, because that is increasingly becoming a focus area for the Munich Security Conference—which started as a military-to-military transatlantic organization sixty years ago, with mostly white men smoking cigarettes in the back room and talking about how to beat Russia. Now, MSC is at the forefront of initiating conversations about broadening notions of what national security means, including climate change, artificial intelligence, food security, migratory movements, and other dynamics. And secondly, it’s broadening its appeal and including more voices of the Global South, while maintaining its transatlantic core, whatever that means these days.

MSC has offices in Munich and Berlin, but no other offices outside Germany. The idea was to have ears and eyes on the ground here in Washington, DC, and to establish better relationships with the World Bank, with the International Monetary Fund, with the American Development Bank, with the UN agencies here, like the Food and Agriculture Organization, World Food Program—and these offices I used to work a lot with when I was at the U.S. Agency for International Development, rest in peace.

Then also, we are looking into engaging a new generation of political representatives of the United States, especially from minority communities that—especially when they have migration backgrounds—are interested in domestic policy issues: migration, health care, education, climate, but not necessarily being socialized politically into international affairs.

And since the corridors of power here in Washington are populated by people that know the world, in that sense, by its sheer weight and status as a global power, that is something where we also engage to see how to make sure that younger Europeans and younger Americans that have political responsibility and are active in their respective parliaments work together, talk together, because it’s not a given anymore.

When you think about foreign policy institutions, as far as you’ve experienced them, do you think that there’s a difference between American ones and European ones, in terms of how they operate or how they think about their jobs?

I think the U.S. government is unique, as I mentioned, because they rotate a bunch of people in and out, and it’s easier to go from business to government to think tank, and then back to government. That usually doesn’t happen in Europe because it is heavily civil-servant organized, and people tend to stay there often for their entire professional life. Washington has 200-plus think tanks, and exactly for that reason, the think tank community is so huge, because you have people that will be in government and people that have been in government, in these think tanks. That makes it intellectually attractive, but also politically attractive for people that want to maintain their viability and the set of capacities that can get them back into government.

There’s also a downside, because it makes them very attractive for foreign donors and economic interests that invest in think tanks and try to pursue their particular agenda. But that also means that Washington has a think tank and intellectual policy environment like no other city in the world. Yes, not only because it’s the U.S. capital—that plays a role. Obviously, it generates a lot of international interest, but the fact that 4,300 people lose their jobs every four years, or maybe every eight years, half of them need to—they don’t go to business, they don’t go to universities, and so they end up in the think tank community. So these shops have a function to fulfill.

It’s very different than in any other Western or even Asian country. Many visitors here in Washington say, “How can we build a think tank culture like you have?” It’s just not technically, financially, and logistically possible if you don’t have this osmotic force field between private sector, academia and government in the middle, so people kind of float around over twenty to twenty-five years of their careers.

Today’s foreign policy environment is changing so rapidly and for young people who are looking to enter into the field, it’s so different than it was even a few years ago. Do you think there are particular skills young people should try to cultivate? Is there any advice you have?

I think everybody who tells you that he or she can give you advice that will hold up the next ten or even five years is likely lying. I don’t even know what’s going to happen in November next year. But I think it is fair to say that you need to spend as much time as you can to build an intellectual toolbox to have the instruments to understand rapidly changing global environments and even your own country, as we see here in the United States. It is easier than ever to generate data. There’s nothing that you can’t learn within half a year if you have the intellectual capacity to really understand very basic and fundamental transformations that your generation will see accelerate over the course of the next thirty years.

Maybe, as the philosopher in me would say, spend as much time as you can on understanding historical modernization processes, and understand the interconnection between political economy, establishment of liberal mass societies, social psychology, the public sphere, and make sure that you’re so well qualified that you can go to virtually any part of the world and work yourself into regional environments within a year or so, because this is very likely what you will have to do to understand the world.

It’s completely unclear where we will stand ten or fifteen years from now. It’s unclear whether China will persist with its strong economic and relatively centralized and homogeneous policy and ethnic structure. It’s unclear whether India will be able to cope with the three to four hundred million people that are projected to move from the rural to urban areas in the next generation, or generation and a half. It’s totally unclear how Europe and parts of Asia will deal with the dramatically decreasing fertility rates and what that means to their social pension and health-care systems. And it’s completely unclear whether the United States will be a stable liberal democracy, even eight or ten years from now.

So I would say, be prepared for a lot of surprises, and the best thing to be prepared is to know history, to know the present, and to be well immersed in theory.

That’s all good advice. We want to end on a fun note.

(laughs) Try me.

So gear shift; You’ve done research on all these different parts of the world, I’m sure you’ve traveled extensively for your research. Is there a most memorable work trip or most memorable meal you’ve had while conducting your research?

Quite a few. But I must say, the two trips that I did to what is called the Seven Sisters region of India—Assam, Manipur, Nagaland—like upper right-hand side on the map, connected to the Indian mainland, so to speak, through a tiny corridor with a highway, which is the most highly militarized road in the entire world. That has been really interesting, not only because of the interesting dynamic between the Seven Sister region and the Indian subcontinent, and the racial dimensions, ethnic dimensions, that came into play, but also to see to which degree—especially vis-à-vis in Bangladesh and Myanmar—the wild and irresponsible decolonization of the British Empire still plays out today.

It’s relatively easy to see this in Palestine, but even in regions of the world that we usually do not pay close attention to, it is still visible in daily life and informs many policy conversations. And between being in a very remote part of the world, with one of the most fascinating rhinoceros metro reserves, and then still seeing those colonial traditions popping up in a very modern and digitized and social media-driven political environment, was probably the deepest impression that I had in the last twenty years or so.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. It represents the views and opinions solely of the interviewee. The Council on Foreign Relations is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy.