Taiwan’s Backdoor Currency Manipulation

The CBC’s letter to the Economist was like waving a red flag in front of a bull, especially when the regulators are rigging the hedging market.

Taiwan never targets a level for its currency—at least, that is what the CBC (Taiwan’s central bank), maintains.

It is of course pure coincidence that the CBC’s intervention spiked when the Taiwan dollar appreciated toward 29 last spring.

Or that the CBC intervened heavily in 2018 at 29 TWD to the USD and again in 2020, and 2021 at about 28 TWD/USD.

What looks like intensified intervention around key levels is just smoothing volatility of course (wink). We all know volatility would jump if the central bank defied expectations and let the currency appreciate by more than expected (that’s actually true).

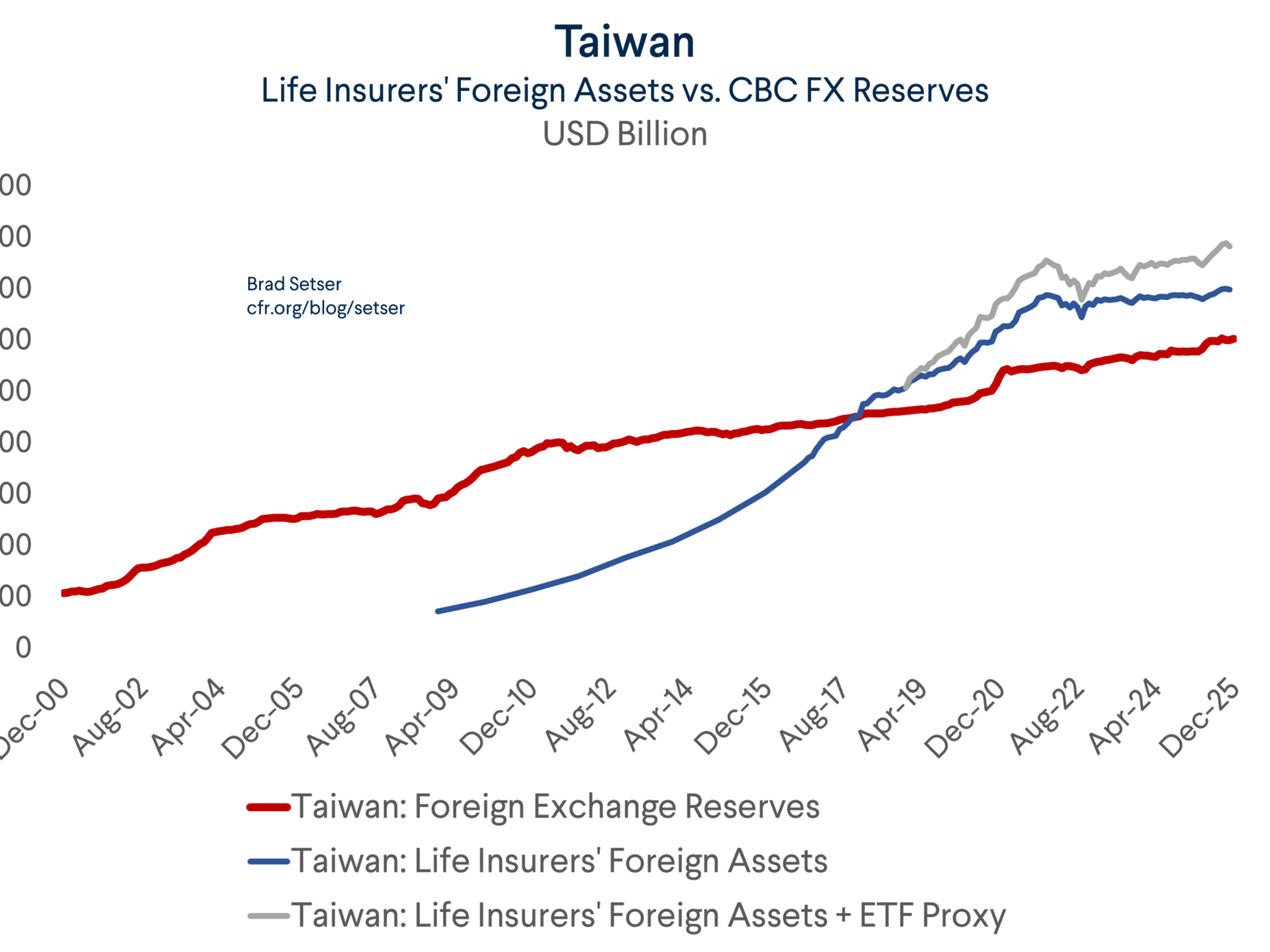

The CBC maintains that it is not worried at all about the impact that any sustained appreciation of the Taiwan dollar would have on the massive open position of Taiwan’s lifers ($200 billion, 25 percent of GDP and over 200 percent of capital). That open position is simply the result of the lifers’ economic decisions in the face of a scarcity of TWD-denominated bonds and low Taiwan dollar rates; it has “not [been] deliberately guided by the CBC”. And it is up to the lifers and their regulators to decide how to best manage the associated risk.

Taiwan’s regulators also don’t focus on the foreign exchange implications of their regulatory decisions. Their recent regulatory decision to allow the lifers NOT to mark their bonds to the foreign exchange market was a simple decision to help protect lifers’ income, capital, and ultimately solvency (wink).

Regulators around the world allow their insurers to hold bonds in a portfolio that isn’t marked to market. Bonds, after all, should converge to face value when they mature.

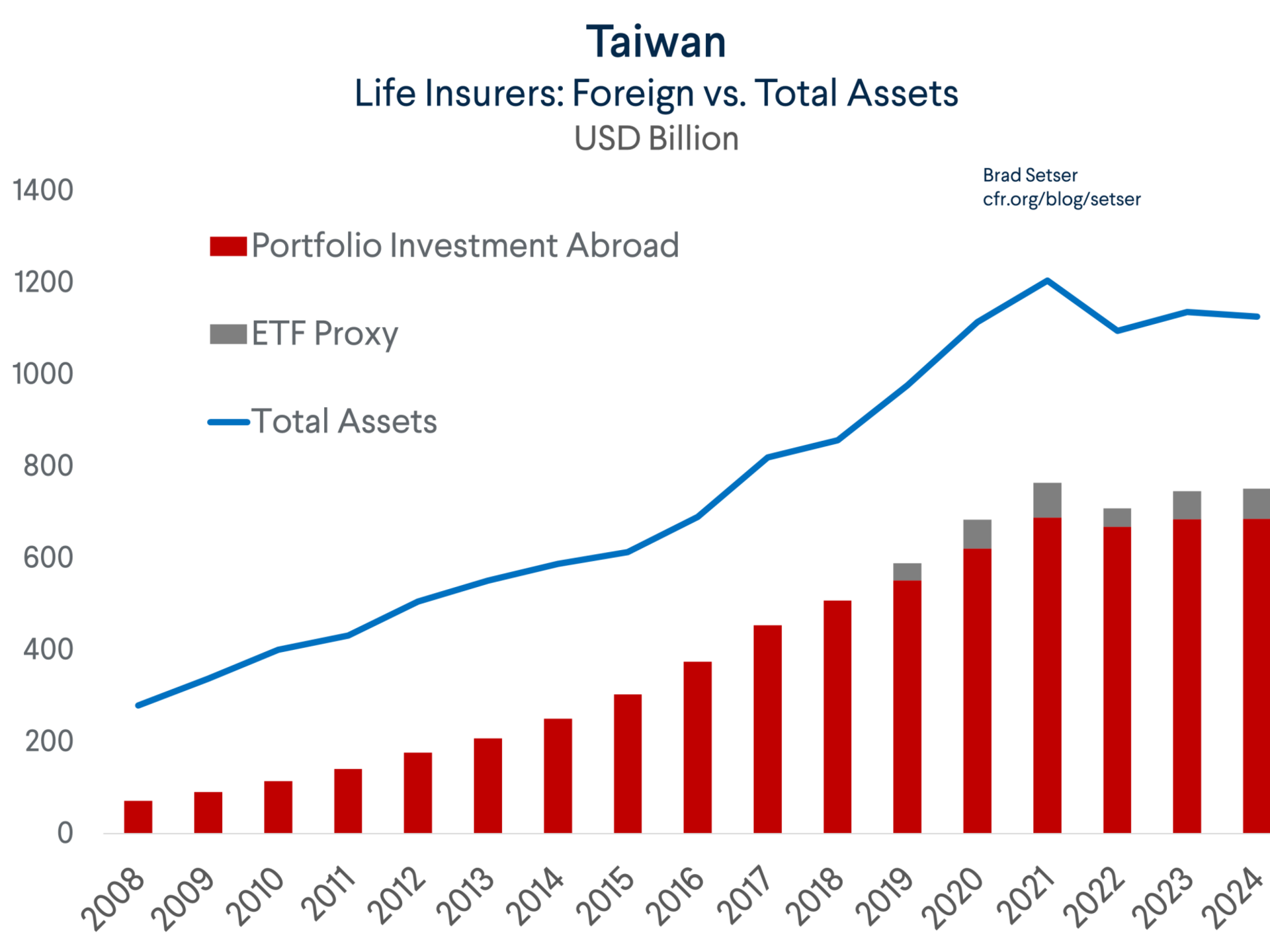

Taiwan’s lifers bought a ton of dollar bonds (almost their entire foreign portfolio is in dollar bonds) in the low-for-long era, and when US rates soared they moved most of their portfolio into the hold to maturity bucket (they thus avoid realizing any immediate loss, but have to hold the bond for a long time and are stuck with bonds that have relatively low coupons).

Taiwan’s regulators have gone a step further.

The insurers are no longer required to mark foreign currency bonds in their hold to maturity bucket to the foreign currency market. Foreign currency losses (or gains) can be more or less amortized over the life of the bond. Bloomberg reports that this idea came, unsurprisingly, from the lifers themselves:

“Taiwan’s life insurers proposed changes to accounting rules earlier this year that would allow exchange rate fluctuations to be partially recognized over time, rather than having their full impact reflected immediately. As a decision on the proposal nears, insurers have been cutting their hedging again.”

But it was adopted by the regulators, the Financial Supervisory Commission:

“Under current standards, short-term exchange-rate movements have caused significant volatility in reported earnings, even though most of these are unrealized … A revised accounting approach is needed to more appropriately present the financial position of Taiwan’s life insurance industry.”

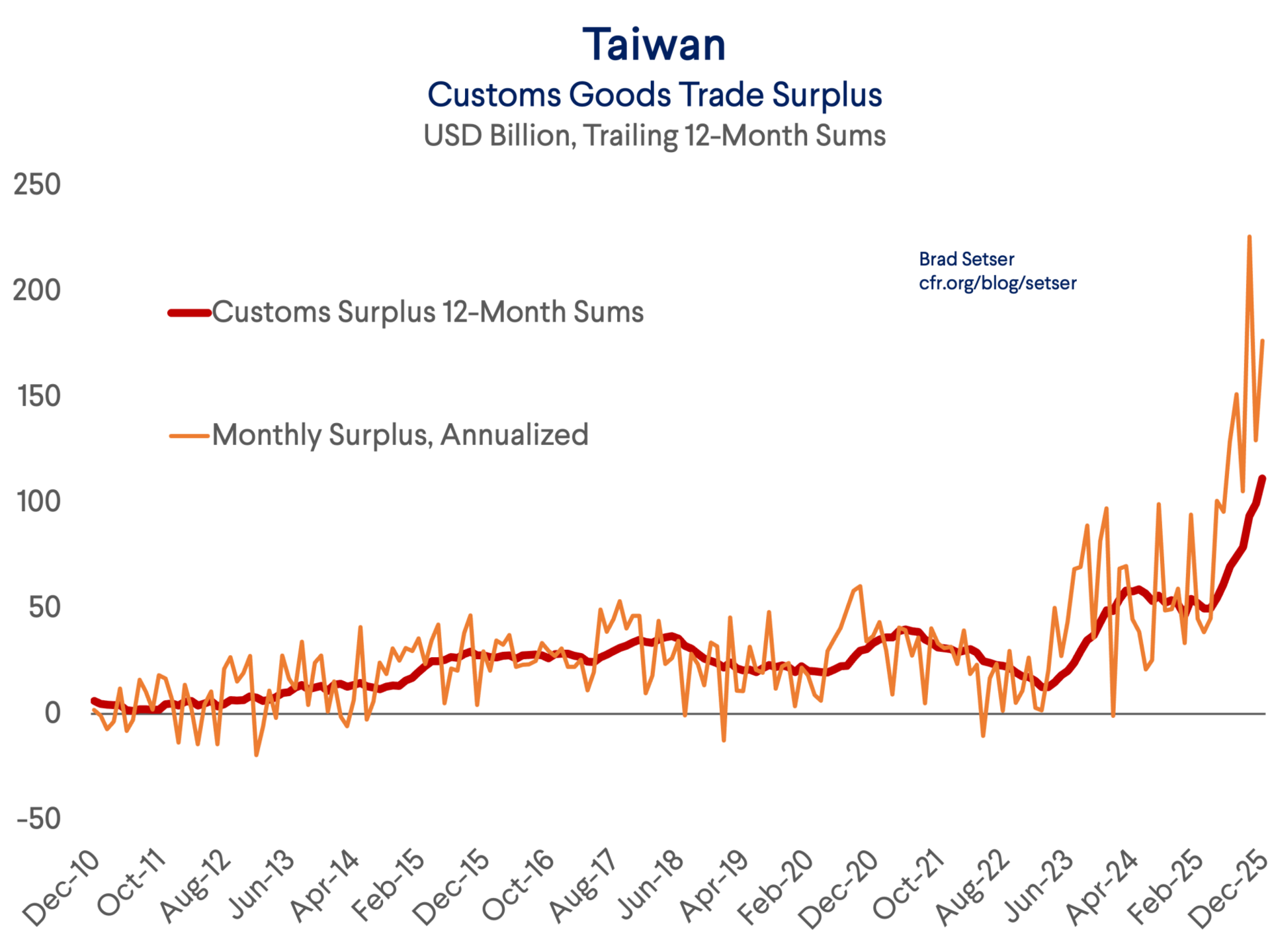

This accounting is indeed novel, as there is no theory stating that the foreign currency market should converge to TWD/USD spot from the time a bond was purchased (or from the time when it was moved into the hold to maturity portfolio). Sure, the Taiwan dollar has historically been rather stable (even though the CBC insists that it of course doesn’t target a level). But the Taiwan dollar is structurally quite undervalued on pretty much every measure and thus there is a strong case that the Taiwan dollar will eventually appreciate (reducing the TWD value of foreign currency bonds in the hold to maturity bucket at the time of maturity). Taiwan’s current account surplus has been around 15% of its GDP recently, and it is is if anything poised to rise toward 20% of GDP on strong demand for AI chips.

This relatively obscure but conceptually wild regulatory change has massive implications for the currency market.

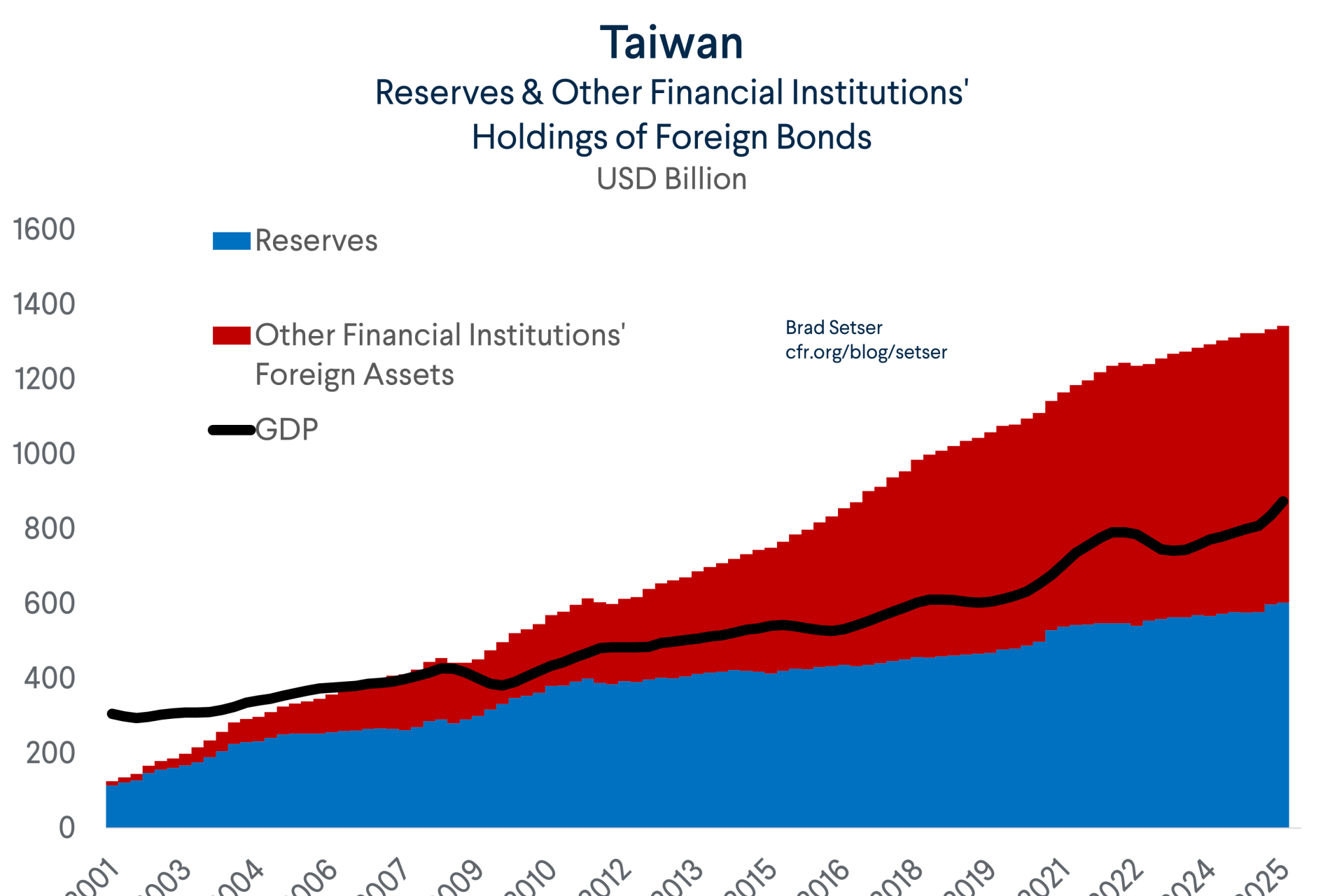

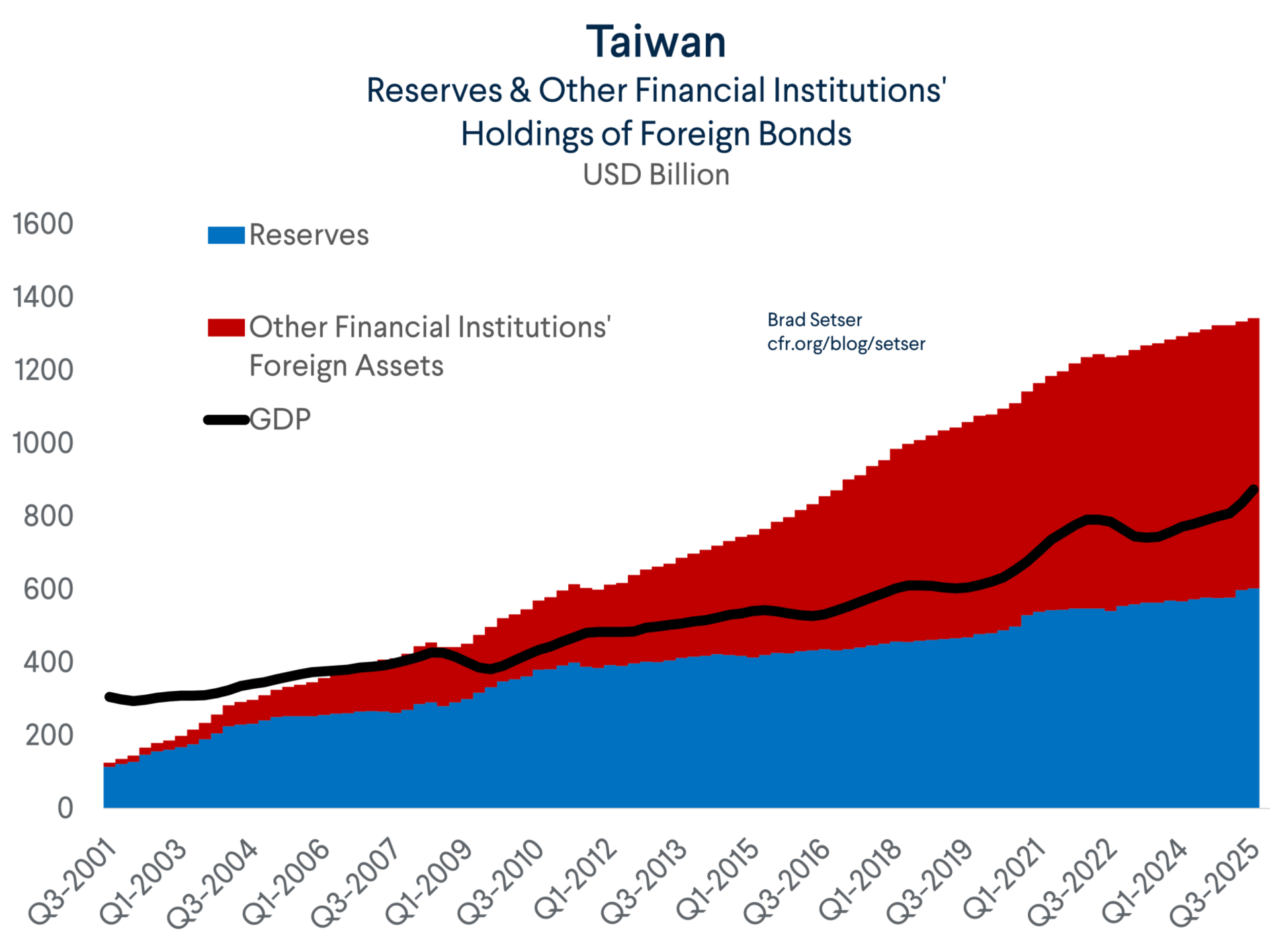

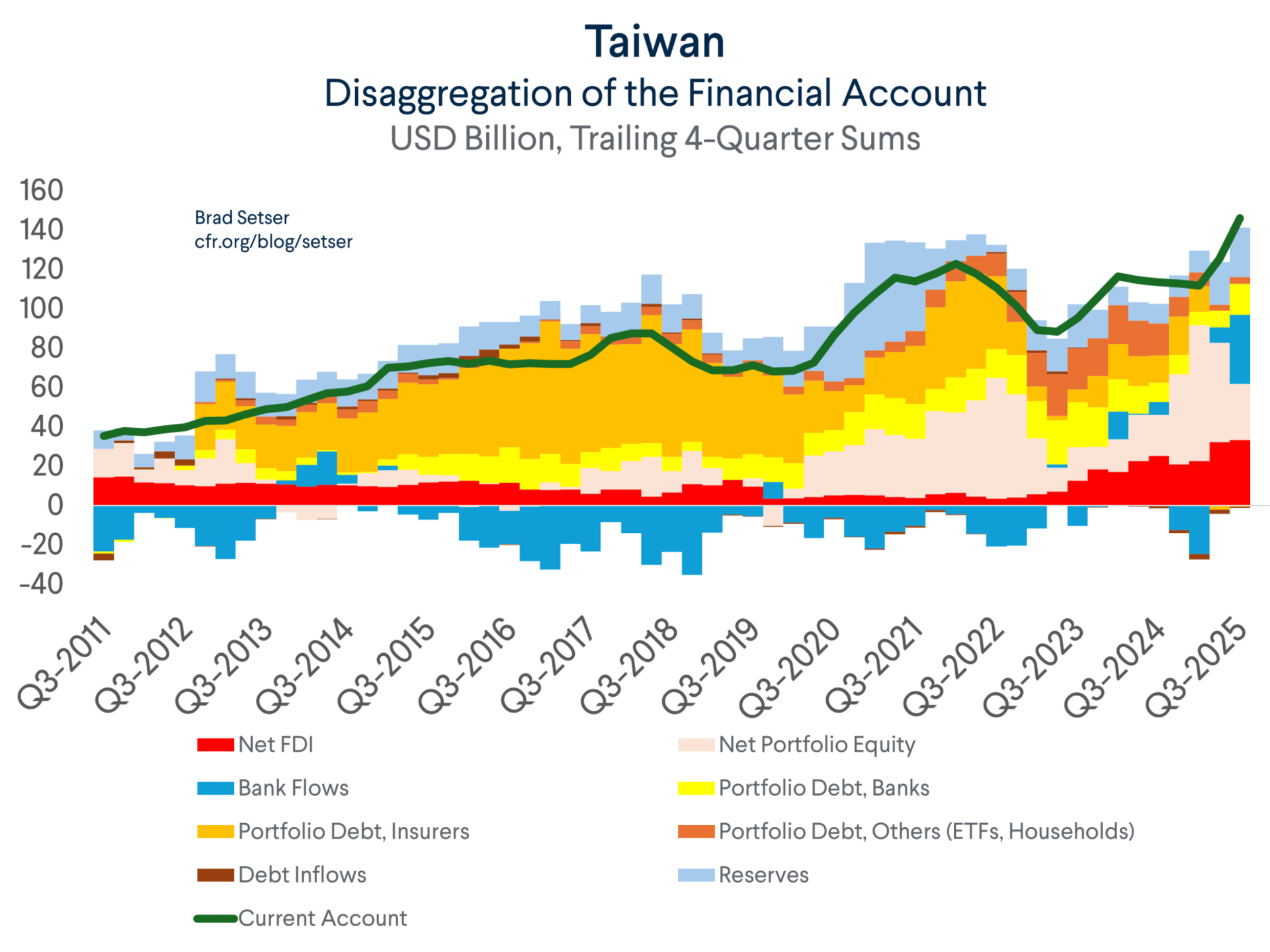

Taiwan’s lifers officially have $700 billion in foreign currency assets (maybe more) and something like $200 in foreign currency-denominated policies. That means that close to $500 billion in foreign currency assets (“NT$15.2 trillion ($483 billion) of the insurers’ assets are exposed to exchange-rate risk, based on regulatory calculations that exclude foreign currency–denominated policies”) is being held against Taiwan dollar liabilities.

That is a huge sum. Over 50 percent of Taiwan’s GDP.

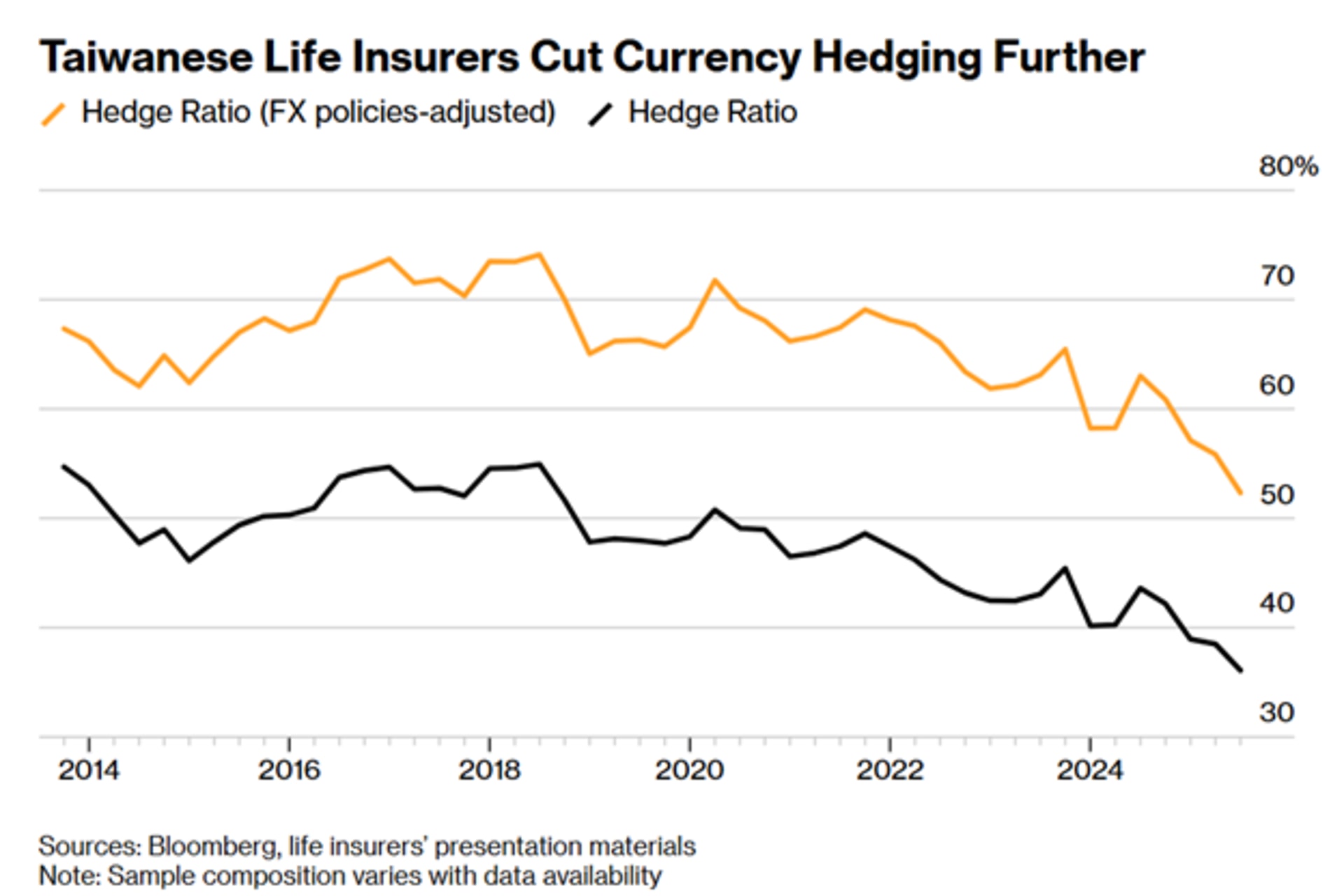

Historically, the lifers have hedged a decent share of this position (and have increased their hedge ratio during periods of volatility).

But hedging is costly.

The interest rate differential at 3 months is over 2 percent, at 10 years it is nearly 3 percent. Moreover, hedging tends to require paying a premium to the rate differential. Fully hedging the lifers $500 billion in net foreign currency assets would eat up most of the lifers’ earnings. Even partial hedging has been costly—the lifers’ income would have doubled if they hadn’t hedged over the last 6 years. Per Bloomberg:

“…from 2019 to 2025, the firms spent over NT$1.6 trillion on currency swaps and non-deliverable forwards to hedge exchange-rate risks — exceeding their combined net income of roughly NT$1.4 trillion over the same period”

The regulator says that ending mark to market accounting on the lifers’ foreign bonds will save them $3 billion a year in hedge costs and that assumes at least some ongoing hedging in the onshore market.*

The lifers have an economic incentive not to hedge and, well, to rely on the central bank to smooth volatility, especially intensely at key levels. And if the lifers reduce their hedge ratio, that will have a potentially significant impact on the foreign currency market.

Suppose that the lifers take their hedge ratio down from 65 percent to 55 percent—a 10 percentage point swing. 10 percent of $500 billion is $50 billion(6 percent of GDP). It is big enough to be a meaningful offset to Taiwan’s $150 billion current account surplus (last 4 quarters through Q3).**

A brief technical interlude. But the way you avoid exposure to big swings in the foreign exchange market is by having liabilities in the same currency in which you have assets. And since the lifers’ true liabilities are in TWD, they have to borrow dollars to generate dollar liabilities, or swap for the dollars, which amounts to the same thing.

As a result, unwinding a hedge basically means buying U.S. dollars (with Taiwanese dollars—a flow that supports the USD against TWD, and helps to keep Taiwan’s currency weak in the face of its massive trade surplus.

Before COVID, the lifers hedged around 70 percent of their foreign currency risk (per Bloomberg), but that was when hedging was cheap.

After Covid, the hedge ratio fell to just above 60 percent (varying a bit form quarter to quarter) and it appears to have fallen from 61 percent to 52 percent for the big lifers over the course of 2025.

Cutting hedges even as foreign currency volatility picked up (the lifers had a bit of a scare back in May) is a somewhat unusual move. As are the new foreign bond purchases that appear to have occurred in the fourth quarter.

But the central bank likely welcomed this move.

Now the central bank could view the open position of the lifers as a problem – as it makes the lifers vulnerable to large shifts in the value of the Taiwan dollar and potentially dictates the CBC’s monetary policy (by requiring that it be directed at the currency rather than domestic monetary conditions; exchange rate dominance).

But the CBC faced a problem after it intervened heavily in the second quarter of 2025. Any further intervention would mechanically put Taiwan on the Treasury department’s manipulation list, as it would push total intervention over four quarters above 2 percent of GDP.

The regulators’ tolerance for a bigger open position provided the solution, at least temporarily.

Indeed, regulatory changes that increase the risk borne by regulated entities while generating a predictable bid for dollars (taking pressure off the central bank) look like backdoor currency manipulation. The effect of the policy was clearly to create a bid for dollars—and that was quite possibly a large share of the intent. The change was certainly well-timed.

Taiwan’s trade surplus has soared. Absolutely soared. After being around $50 billion a year for most of the last decade, it is now running at a $150 billion or so rate in the fourth quarter, largely because TSMC makes the bulk of the world’s AI chips, and can command a premium for doing so.

If this is sustained—and that is a big if—it should drive the current account surplus up from around $100 billion a year to close to $200 billion a year (a crazy number—over 20 percent of GDP).

Some of the surplus is recycled into new foreign investments by TSMC itself.

But TSMC’s external investments are “only” $50 billion a year, well below the massive current account surplus.

So, if the central bank of China wants to stay out of the market while keeping the Taiwan dollar stable at a level that doesn’t generate new (even if now hidden) losses for the life insurers, there needs to be a massive outflow from Taiwan.

Part of that comes from the fact that the new regulations have led the lifers, already overweight foreign assets, to resume their purchases. Part of that comes from the reduction in hedging, which basically means buying dollars to retire existing hedges.

Now much of the move has shown up in the offshore non-deliverable forwards (NDFs) market, where the traditional premium on hedging (from the lifers’ demand) has disappeared. But there will no doubt be echoes in the onshore market, especially once the lifers have closed out nearly all their NDFs.

The only real question is just how far the hedge ratio can fall.

The 10 percent move last year raised the open position from around $190 billion to more like $230-235 billion. If the hedge ratio falls to 40 percent -- as the spokesperson of Taiwanese insurer Cathay Life and the vice-chair of Taiwan’s life insurance industry associations predicted (“Lin Chao‑ting [of Cathay]said in November that the hedging ratio is expected to fall to about 40%, from roughly 60%”) the open position rises to $300 billion. And if the hedge ratios goes all the way down to 20 percent, the open position goes to $400 billion (50 percent of GDP).**

Combine that with credible estimates of the Taiwan dollar’s long-term undervaluation (see the great coverage in the Economist) and the insurers and the central bank are taking on one hell of a long-term risk for a bit of short-term gain.

Particularly if the CBC doesn’t target a level of the Taiwan dollar and only smooths volatility (ha!).

And all the more so the US Treasury ever concludes that the real way to get TSMC to invest abroad is to reduce the current exchange rate incentive for TSMC (Taiwan is super cheap) to keep most of its production in Taiwan, as there is no real doubt that Taiwan, Inc (The CBC, but also the regulators) does work together to maintain an artificially weak currency despite the CBC’s rather unpersuasive denials.

* A friend in the market has noted that the remaining hedges will likely have to be marked to market, as they include many short-term instruments and thus the profit and loss is realized frequently at maturity (the CBC does provide some very long-term hedges). That could create a different type of volatility, as the assets wouldn’t be marked to market, but the foreign currency liabilities created by hedging would be. The incentive then is to reduce volatility by bringing the hedge ratio down. Or perhaps the regulators will come up with a clever fix (i.e., rolled over hedges aren’t marked to market if the assets aren’t?)

** A 20% swing in the life insurers hedge ratio is functionally equivalent to around $100 billion (12-13% of GDP) in foreign exchange purchases by the central bank. The U.S. Treasury has indicated that it will account for the activities of state banks and sovereign funds in its upcoming foreign exchange rate report. There is a strong case it should also look at regulatory decisions that have a predictable impact on the foreign currency market.

** Such moves of course would be a real risk if the CBC weren’t willing to intervene to block appreciation, and since the CBC only smooths volatility, one might think the regulators would worry about this risk. But such thoughts lead in a dangerous direction (the CBC might send me a nasty letter).