Emerging Markets Under Pressure

Emerging markets have come under a bit of pressure recently, with the combination of the dollar’s rise and higher U.S. ten year rates serving as the trigger. The Governor of the Reserve Bank of India has—rather remarkably—even called on the U.S. Federal Reserve to slow the pace of its quantitative tightening to give emerging economies a bit of a break. (He could have equally called on the Administration to change its fiscal policy so as to reduce issuance, but the Fed is presumably a softer target.)

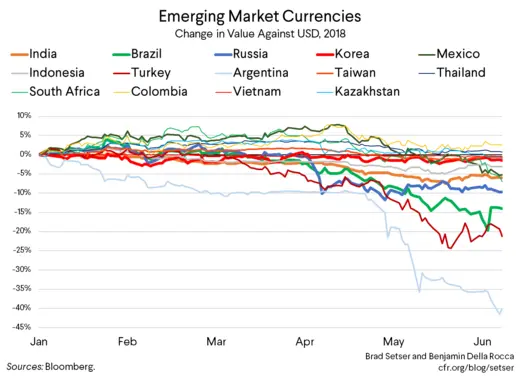

Yet the pressure on emerging economies hasn’t been uniform (the exchange rate moves in the chart are through Wednesday, June 13th; they don’t reflect Thursday’s selloff).

That really shouldn’t be a surprise. Emerging economies are more different than they are the same.

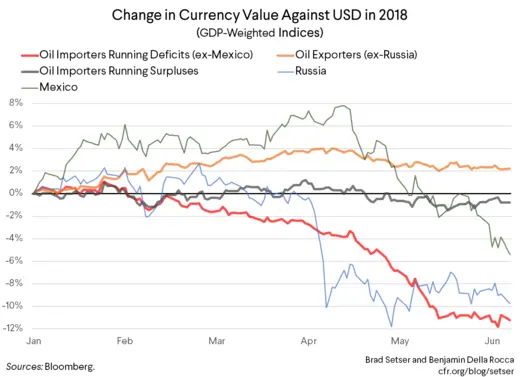

With the help of Benjamin Della Rocca, a research analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations, I split emerging economies into three main groupings:

- Oil importing economies with current account deficits

- Oil importing economies with significant current account surpluses (a group consisting of emerging Asian economies)

- And oil-exporting economies

It turns out that splitting Russia out from the oil exporting economies makes for a better picture. The initial Rusal sanctions were actually quite significant (at least before Rusal got a bit of a reprieve). And, well, Mexico is a bit of a conundrum, as it exports (a bit) of crude but turns into a net importer if you add in product and natural gas.

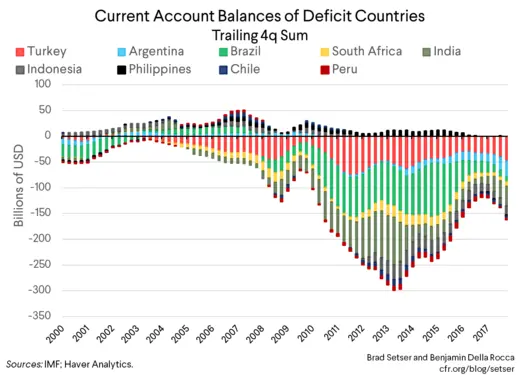

But there is clearly a divide between oil importers with surpluses (basically, most of East Asia) and oil importers with deficits. The emerging economies facing the most pressure, not surprisingly, are those with growing current account deficts and large external funding needs, notably Turkey and Argentina.

In emerging-market land, at least, trade deficits still matter.

In fact, those that have experienced the most depreciation tend to share the following vulnerabilities:

- A current account deficit

- A high level of liability dollarization (whether in the government’s liabilities, or the corporate sector)

- Limited reserves

- Net oil imports

- Relatively little trade exposure to the U.S., leaving little to gain from a stimulusinduced spike in U.S. demand

- Doubts about their commitments to deliver their inflation targets, and thus the credibility of their monetary policy frameworks.

It is all a relatively familiar list.

Though to be fair, Brazil has faced heavy depreciation pressure recently even though it has brought its current account down significantly since 2014.* Part of the real’s depreciation is a function of the fact that Brazil and Argentina compete in a host of markets, and Brazil must allow some depreciation to keep pace with Argentina. Part of it may be a function of market dynamics too, as investors pull out of funds with emerging market exposure, amplifying down moves. And of course, part of it comes from increasingly pessimistic expectations for Brazil’s ongoing economic recovery—driven by uncertainty ahead the coming presidential elections together with a quite high level of domestic debt.

And for Mexico, well, elections are just around the corner and uncertainty about the future of NAFTA can’t be helping…

* Brazil also benefits from having much higher reserves than either Turkey or Argentina. Its reserves are sufficient to cover the foreign currency debt of its government as well as its large state banks and firms in full. This has given the central bank the capacity to sell local currency swaps to help domestic firms (and no doubt foreign investors holding domestic currency denominated bonds) hedge in times of stress. But Brazil’s reserve position is a topic best left for another time.