Southeast Asia Seeks New Partners in the Era of “America First”

Amid uncertainty over U.S. foreign policy, countries across Southeast Asia are looking to build up strategic partnerships with regional powers to counter an increasingly assertive China.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

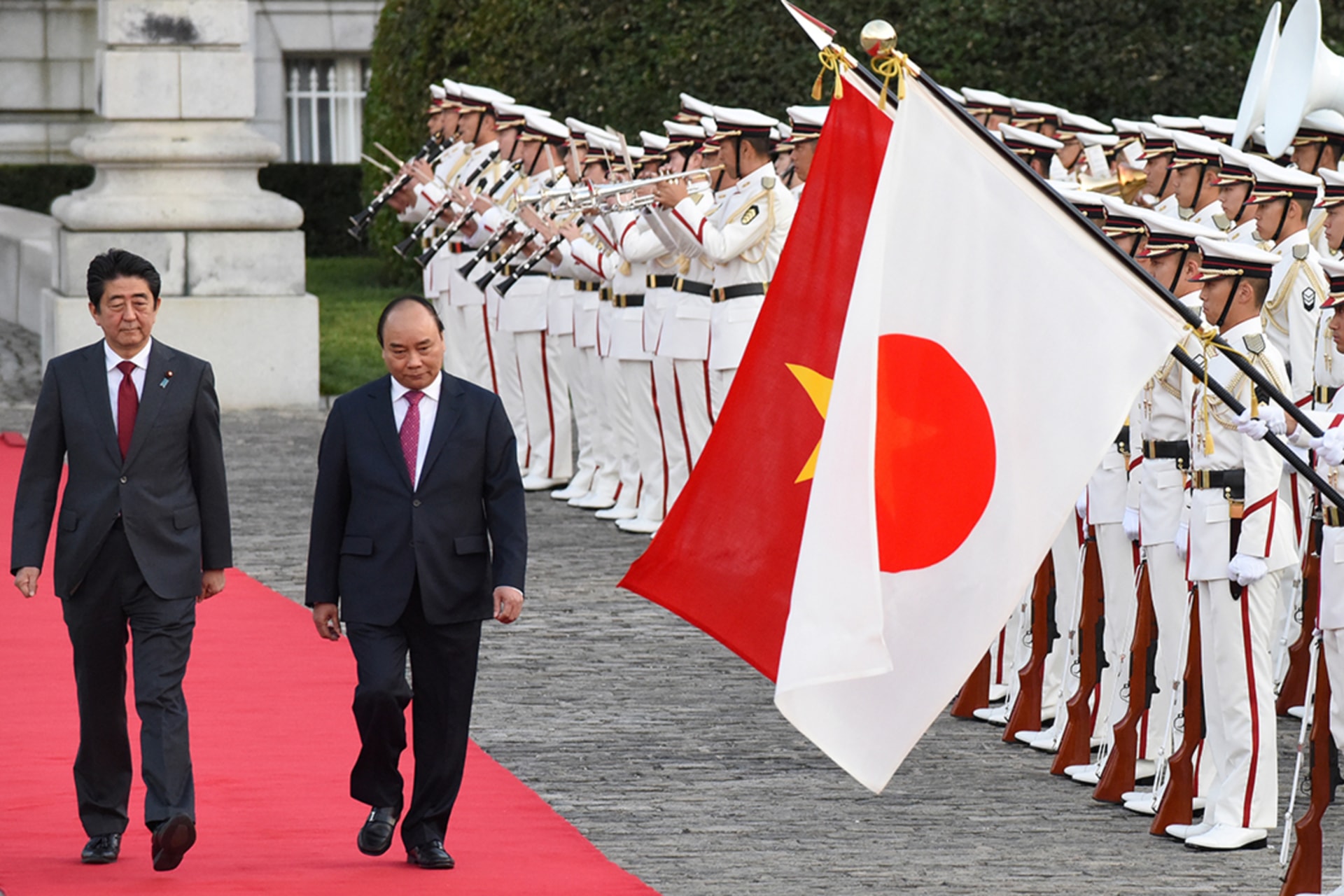

As I noted in a blog post last week, Vietnam, while welcoming the visit of a U.S. aircraft carrier and continuing strong defense ties with the United States, is simultaneously diversifying its set of strategic partners. Hanoi has reached out to South Korea and Australia to play a larger role in the South China Sea, although the two have not necessarily been responsive, and has pushed to upgrade its strategic ties with Japan, which sees Vietnam as a vital, and growing, partner in Southeast Asia. Vietnam also enjoys historically strong links with Singapore. Most importantly, however, Hanoi is rapidly building a major strategic partnership with India, a country with naval capacities and the desire to play a prominent role in the South China Sea, no matter what reaction India’s decisions provoke from Beijing, which stands it apart from other regional powers like Australia.

Vietnam, along with Singapore, is probably the Southeast Asian state most skeptical of China’s regional ambitions, and how China’s rise might affect Southeast Asian security, yet searching for a broader range of strategic partners is increasingly common in the region. I would not go so far, as Parag Khanna of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy suggests, to say that essentially countries in Southeast Asia do not care about U.S. leadership, are becoming totally alienated from Washington, and are building their own regional order. It is true that China has launched its Belt and Road Initiative and its Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade agreement, although it remains to be seen how fully countries in the region will embrace the RCEP. And, yes, Asia-Pacific states (including Vietnam, Singapore, and Malaysia) pushed the Trans-Pacific Partnership forward to completion after the United States withdrew from the trade deal, a sign of their growing clout in regional trade policy.

But Vietnam, Singapore, and even Malaysia, Indonesia, and to some extent Thailand and the Philippines still look to the United States for regional leadership on both traditional and nontraditional security issues, and remain (to varying levels) uncomfortable with the prospect of China fully assuming that mantle. The trade deals are important signposts of Asian countries fully taking trade liberalization into their own hands, but they do not connote a coherent regional strategic order. And in Northeast Asia, there is even less of a chance of an alternative regional order developing any time soon than in Southeast Asia.

Instead of Southeast Asia necessarily abandoning U.S. strategic ties in the era of America First, and embracing links to China, states are indeed pursuing options like Vietnam. (There are exceptions, to be sure, like Cambodia, which seems to have mostly embraced China’s dominance of the region, and to some extent Thailand, where military and business leaders are more comfortable with a China-centered region than many other Southeast Asian leaders.) These include trying to clearly integrate India into Southeast Asia as a more forceful counterweight to China and hedge against a declining United States. They include peninsular Southeast Asian states improving their historically weak cooperation in intelligence gathering and strategic cooperation against nontraditional security threats like terrorism and piracy, in areas like the waters between the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. They include efforts by multiple states, like Vietnam, to push Japan, South Korea, and Australia to play much larger roles in regional security efforts, whether or not (in the case of Japan and Australia) those efforts come within a U.S. network of relationships or not.

In a series of posts over the coming weeks, outside authors and myself will examine how specific Southeast Asian states are seeking to diversify their strategic partnerships, beyond a binary choice between Beijing and Washington.