Transition 2025: Events Will Test Donald Trump’s Foreign Policy Promises

Each Friday, I examine what is happening with President-elect Donald Trump’s transition to the White House. This week: Donald Trump is inheriting a difficult foreign policy inbox that may only get more challenging.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

Years ago, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was asked what might keep him from fulfilling his promises to the voters. He is said to have replied, “Events, dear boy, events.”

Macmillan’s remark comes to mind as Donald Trump prepares to take office in just five weeks. He has vowed to solve America’s problems. The question on the lips of policymakers and pundits alike is how far and how fast he will go in changing U.S. foreign policy. That discussion is hobbled by three things: Trump’s foreign policy comments on the campaign trail were long on boasts and short on specifics, his foreign policy team reflects a wide range of viewpoints and experience, and his deeds frequently fall short of his words.

The collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime over the weekend adds another complication in assessing what Trump will do on foreign policy—events. On that score, Trump is inheriting a much messier world in 2025 than he did in 2017. Russia is waging war on Ukraine. China is intensifying its pressure on Taiwan. North Korea continues to grow it nuclear arsenal, while Iran could soon follow suit. All four countries have increased their bilateral cooperation, raising the prospect that an “axis of autocracies” that will contest and exhaust U.S. power.

Trump has argued for months that all would have been well with the world had he been president for the past four years. Whether that claim is true or not is unknowable. But ultimately it does not matter. As of January 20, he will be the one the responsible for how the United States responds to the challenges it faces. Complaints about what his predecessor botched will carry less and less weight with voters with each passing week. They will just be interested in whether what he does works.

Trump may surprise his many doubters. The growing stresses on the Russian economy might push Vladimir Putin to negotiate on Ukraine. Iran might similarly embrace diplomacy as its “axis of resistance” crumbles in the face of Israeli attacks and the fall of the Assad regime. China might trim its sails because, as Trump put it, Xi Jinping “knows I am f____ crazy.” And North Korea might be willing to talk to Trump in the way it was not with the Biden administration.

But events could also expose the contradictions in Trump’s foreign policy thinking as well as the disagreements and limitations of his national security team. How will Trump respond if Russia makes major advances in Ukraine, China increases its pressure on Taiwan, Syria begins to resemble Libya, Iran goes nuclear, or some crisis no one is currently discussing erupts? Championing a policy of nonintervention while also promising to come down hard on adversaries works on the campaign trail. It will not work in the Oval Office.

Trump has long insisted that he excels at the art of the deal. The foreign policy inbox that he is inheriting will certainly test that claim.

The Vote

The partisan balance in the House of Representatives has finally been settled. It will have 220 Republicans and 215 Democrats. However, with Matt Gaetz having resigned his seat and Mike Waltz and Elise Stefanik about to, the House that convenes in January will operate at the start with a 217-215 edge for the Republicans. The special elections to fill those seats, which Republicans will almost certainly win, will not come until the spring. That means that the House Republican Conference could have difficulties for the next several months acting moving major legislation. If just one Republican legislator defects, a united Democratic caucus can block action on a bill.

What Trump Is Saying

Trump may not yet be president, but he is nonetheless making himself felt on the world scene. Just before Thanksgiving, he threatened to impose 25 percent tariffs on Canada and Mexico and 10 percent tariffs—on top of any other tariffs—on China if the three countries did not do more to stop the flow of fentanyl and immigrants into the United States. The threat likely violates the terms of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement that Trump negotiated in 2018. But legal niceties tend to give way to raw power when the two clash. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a quick trip to Mar-a-Lago to press Canada’s case. Trump called it “a very productive meeting.” However, he raised one issue that Trudeau probably had not prepared for, namely, that Canada should become America’s fifty-first state. Canadian officials said it was a joke. If so, it was one that Trump did not let drop. This week he called Trudeau a “governor” and Canada a “great state.”

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum took a different approach. She wrote a blunt letter to Trump laying out the steps that Mexico had taken to curtail migration to the United States, blaming the fentanyl crisis on America’s insatiable demand for drugs, and noting that Mexico can also play the tariff game. Sheinbaum and Trump subsequently spoke by phone. While both agreed it was a productive call, they disagreed on what they discussed. Trump said that Sheinbaum had agreed to stop “Migration through Mexico.” Her response was that “Mexico’s stance is not to close borders but to build bridges between governments and peoples.”

Trump’s tariff threats did not stop with Canada, China, and Mexico—which happen to be America’s top three trading partners. He also vowed to impose 100 percent duties on BRICs countries if they try to create a rival currency to the U.S. dollar. The organization, which is named for Brazil, Russia, India, and China, but which now includes nine countries, has discussed creating an alternative financial system to the dollar, mostly at Russia’s prodding. The effort has yet to go anywhere, both because it is hard to do and some BRICS countries do not see the move being in their interest. But Trump’s threat shows why other countries might want such an alternative: U.S. dominance of the global financial system gives it leverage it can use against other countries. The extensive U.S. financial sanctions on Russia are a case in point.

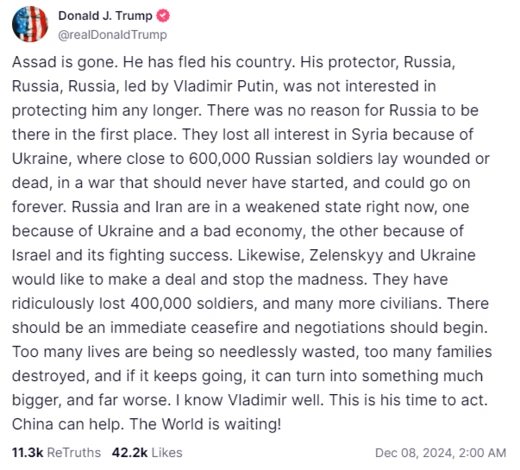

Trump was in Paris over the weekend at the invitation of French President Emmanuel Macron to attend the reopening of Notre-Dame Cathedral. While in the City of Lights, Trump met with Macron and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to discuss ways to end the war in Ukraine. It was Trump’s first meeting with Zelensky since his election last month, and it followed up on discussions that Trump aides have recently had with Ukrainian officials. The three leaders did not come to any agreement. After the meeting, Trump did post on Truth Social calling on Russian President Vladimir Putin to negotiate the war’s end. “I know Vladimir well. This is his time to act. China can help. The World is waiting!”

Putin has given no signs that he is willing to end the war on any terms other than those he dictates, but again, a deteriorating Russian economy might force his hand.

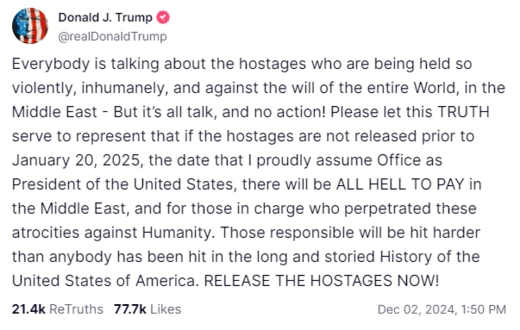

Trump has sent mixed signals recently on how he will approach the Middle East. At the start of the month, he posted that “there will be ALL HELL TO PAY in the Middle EAST” if all the remaining hostages taken by Hamas on October 7 are not released before January 20.

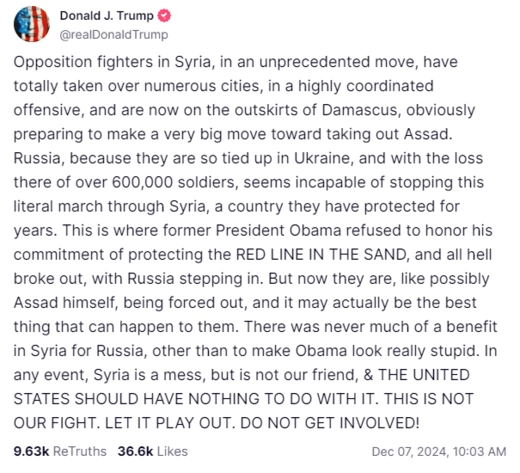

He did not spell out what he would do or who he would do it to. Then this past weekend, after the Assad regime fell, he warned against U.S. involvement in Syria’s affairs.

However, even if Syria “is not our friend,” what happens there matters to the United States given bipartisan U.S. support for Israel among other interests. Paying too little attention to a country can be just as dangerous as too much attention.

Trump sat down with Kristen Welker, the moderator of NBC News’ Meet the Press, for his first media interview since being elected.

Most of the interview discussed Trump’s domestic policy plans and the possibility he might seek retribution against his political opponents. On foreign policy, he hit on many of the themes that have been a hallmark of his political rise. He said his administration would do something “very strong, very powerful” on the border and insisted that tariffs “cost Americans nothing.” He argued that the trade deficits the United States is running with Canada and Mexico means Americans are subsidizing them, and “if we’re going to subsidize them, let them become a state.” And he insisted, incorrectly, that U.S. spending on Ukraine far exceeds what Europe has provided. He did, say, however, that he would keep the United States in NATO if the Europeans “pay their bills.”

What the Biden Administration Is Doing

The Middle East has kept the Biden team busy during its final weeks in office. Biden hailed Assad’s fall from power as a “moment of historic opportunity for the long-suffering people of Syria to build a better future for their proud country.” At the same time, U.S. forces conducted dozens of strikes against ISIS-affiliated bases and groups across eastern Syria. Biden has no plans to withdraw the nine hundred U.S. troops currently stationed in eastern Syria. That may change when Trump takes office. He proposed ending the U.S. military presence in Syria in 2018 but retreated in the wake of criticism from congressional Republicans. Trump has not, to this point at least, criticized Biden for the recent round of U.S. attacks on ISIS forces in Syria.

The news out of Syria has overshadowed the Biden administration’s success in helping negotiate a ceasefire in southern Lebanon between Israel and Hezbollah. Sporadic missile strikes and skirmishes have continued, and Amos Hochstein, the Biden official who led the shuttle diplomacy to get the deal done, has criticized Israel for violating its provisions. Nonetheless, the ceasefire is holding in the main, and the Biden administration has moved forward with a $680 million arms package to replenish Israel’s military supplies.

The Defense Department announced on December 2 that it is providing Ukraine with an additional $725 million in military aid. The announcement came as Secretary of State Antony Blinken headed to Europe for the NATO foreign ministers summit looking to solidify continued aid to Ukraine. Meanwhile, the Biden administration continues to urge Congress to provide a $24 billion in additional security assistance. That effort looks to be an exercise in futility. House Speaker Mike Johnson says he will not bring the aid package to the House floor for a vote. Even if Johnson changes his mind, passing additional funding would not tie Trump’s hands on Ukraine. The Pentagon still has billions unspent from existing authorized Ukraine spending. That means that the Trump administration will decide whether Ukraine receives more U.S. aid or not.

The Biden administration announced new restrictions on the sale of advanced semiconductor chips and technology to China. The restrictions, however, may be less binding than they appear at first glance. Several of the provisions come with potential exemptions that technology firms are likely to request.

Trump’s Appointments

Trump has been busy filling slots on his foreign policy and national security team. He named Alex Wong to be his deputy national security advisor. Wong was deputy assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific affairs and deputy special representative for North Korea during Trump’s first term. The forty-four-year-old holds a degree from Harvard Law School. He practiced international law before becoming a legal advisor to the State Department, an advisor to Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign, and then foreign policy advisor and general counsel for Republican Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas.

Trump named Sebastian Gorka deputy assistant to the president and senior director for counterterrorism on the staff of the National Security Council. The fifty-four-year-old Gorka was part of the White House Strategic Initiatives Group in the first Trump administration but was pushed out when Gen. John Kelly became chief of staff in July 2017. Gorka is a polarizing figure. Trump’s former National Security Advisor John Bolton has called him a “con man.” Michael Anton, a former Trump national security official, reportedly withdrew from consideration to be deputy national security advisor upon learning he would have to work with Gorka.

Speaking of Anton, Trump named him to be director of policy planning in the State Department. Policy Planning was created in 1947—George Kennan was its first director—with the objective, as Secretary of State Dean Acheson put it, of anticipating “the emerging form of things to come, to reappraise policies which had acquired their own momentum and went on after the reasons for them had ceased, and to stimulate and, when necessary, to devise basic policies crucial to the conduct of our foreign affairs.” Anton was the author of “The Flight 93 Election,” which he wrote in 2016 for the Claremont Review of Books under a pseudonym. The gist of his argument was that conservatives should gamble on supporting Trump because Hillary Clinton’s election would doom all that conservatives held dear. Or as Anton put it: “a Hillary Clinton presidency is Russian Roulette with a semi-auto. With Trump, at least you can spin the cylinder and take your chances.”

Christopher Landau is Trump’s nominee to be deputy secretary of state. A lawyer by training—he clerked for both Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas on the U.S. Supreme Court—and the son of a U.S. diplomat, Landau served as U.S. ambassador to Mexico from 2019 to 2021. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum applauded the nomination, as did many Latin America experts in the United States. The combination of Marco Rubio and Landau means that the upper echelon of the State Department will for the first time have deep Latin America experience.

Stephen Feinberg, the co-chief executive of the private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management, is Trump’s pick to be deputy secretary of defense. Feinberg sat on the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board during Trump’s first term. Cerberus Capital Management has invested in defense companies and production, potentially creating conflict-of-interest problems for Feinberg.

Trump tapped Jamieson Greer, a protégé of trade hardliner Robert Lighthizer, to be U.S. Trade Representative. An Air Force veteran and trade lawyer, the forty-four-year-old Greer has argued that the United States should pursue a “strategic decoupling” from China and revoke its permanent normal trading status. One interesting consequence of the Greer announcement is that it appears that Lighthizer has been shut out of a senior position in the administration. He had been rumored as a possible candidate for secretary of commerce or treasury.

It is an open question how much influence Greer will have over trade policy. When Howard Lutnick to be Commerce Secretary, Trump said that Commerce Department would have “additional direct responsibility for the Office of the United States Trade Representative.” Trump also named Peter Navarro to be senior White House counselor for trade and manufacturing. Navarro was a top trade aide to Trump during his first term and served a four-month sentence for refusing to cooperate with the January 6 congressional committee. So several officials will have a say in U.S. trade policy, which could lead to some bitter bureaucratic infighting.

Trump turned to retired Lt. Gen. Keith Kellogg to serve as special envoy for Ukraine and Russia. Kellogg served for thirty-three years in the U.S. Army and fought in Vietnam. He served in the first Trump administration as chief of staff and executive secretary of the National Security Council, interim national security advisor, and then national security advisor to Mike Pence. He co-wrote a policy paper earlier this year that argued that the United States should:

seek a cease-fire and negotiated settlement of the Ukraine conflict. The United States would continue to arm Ukraine and strengthen its defenses to ensure Russia will make no further advances and will not attack again after a cease-fire or peace agreement. Future American military aid, however, will require Ukraine to participate in peace talks with Russia.

To convince Putin to join peace talks, President Biden and other NATO leaders should offer to put off NATO membership for Ukraine for an extended period in exchange for a comprehensive and verifiable peace deal with security guarantees.

It is anyone’s guess whether Kellogg’s proposal is what Trump has in mind when he says he will end the war in Ukraine in a day.

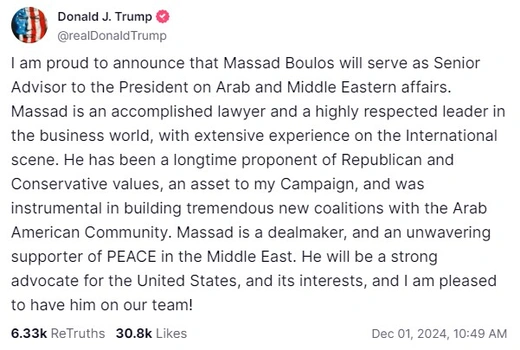

Trump also named the fathers of two of his children’s spouses to foreign policy posts. He named Massad Boulos, Tiffany Trump’s father-in-law, to be a senior White House adviser on Arab and Middle Eastern affairs.

Boulos was born in Lebanon to a prominent Greek Orthodox family and worked in the trucking business in Nigeria. He says he is a billionaire. That appears to be far from the truth. He also has said that he has not been to the Middle East for years. It is unclear how responsibility for U.S. policy in the region will be allocated among Boulos, Steven Witkoff, Trump’s special envoy for the Middle East, and the secretaries of state and defense with their substantial staffs.

Trump named Charles Kushner, Ivanka Trump’s father-in-law, to be the U.S. ambassador to France.

Kushner is a wealthy New Jersey real estate investor who was sentenced to twenty-four months in federal prison in 2005 after pleading guilty to several charges stemming for making illegal campaign contributions. Trump pardoned Kushner in 2020. It is common for presidents to name wealthy supporters to plum diplomatic assignments. What is uncommon is for a nominee to have been convicted of a felony.

The Kushner nomination was just one of Trump’s ambassadorial picks. He tapped former Republican Senator David Perdue of Georgia to be ambassador to China. Perdue positioned himself as a China hawk when he was in the Senate for 2015 to 2021. Before entering politics, Perdue was a businessman who spent a good portion of his career working for firms in Asia. Trump also tapped billionaire Tom Barrack to be ambassador to Turkey. Barrack was tried and acquitted in 2022 of violating the Foreign Agents Registration Act with his business dealings in the United Arab Emirates.

What the Pundits Are Writing

The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer wrote a lengthy and unflattering profile of Trump’s pick for secretary of defense, Pete Hegseth. Among other things, Mayer documented that while president of the non-profit Concerned Veterans for America, Hegseth was accused of excessive drinking, sexual harassment, and financial improprieties. The New York Times’s Sharon LaFraniere and Julie Tate reported that Hegseth’s mother sent her son an email in 2018 lambasting him for mistreating women. In one passage she complained: “On behalf of all the women (and I know it’s many) you have abused in some way, I say … get some help and take an honest look at yourself.” As LaFraniere and Tate also reported that Mrs. Hegseth told them that she later sent Hegseth a follow-up email apologizing for writing “in anger, with emotion.” Despite these reports, Trump is sticking by Hegseth.

Michael Hirsch wrote in Politico that Trump will struggle to get deals on the war in Ukraine and the fighting in Gaza. Hirsch’s main argument is that “in the four years since he [Trump] left the Oval Office, the world has moved on, changing in ways that mean he faces a much harsher international environment than last time—an environment that makes it unlikely that even the wars in Ukraine and the Mideast, which have exhausted all sides, will end anytime soon.

Foreign Policy’s Keith Johnson explored Trump’s tariff plans. He concluded that “what makes it hard for economists to model and other countries to understand is that nobody, even in Trump world, seems to know exactly why tariffs are on the table. Trump himself has suggested using tariffs as a replacement for the entirety of U.S. federal income tax revenue; at the very least, Trump and his brain trust are relying on enhanced tariff revenue to offset the falling revenues that will come from a renewal of his 2017 tax cuts, which are set to expire next year and are an early priority for the incoming administration.” New tariffs, however, will not go far in making a significant dent in the U.S. government’s budget deficit, which was $1.8 trillion in FY24. The United States imports about $3 trillion worth of goods a year. So a 10 percent tariff would bring in about $300 billion in additional tax revenue, with all other things being equal, as economists like to say. (Actually, they like to say ceteris paribus.) But all other things will not be equal. Tariffs make imports more expensive, so people buy less of them, which reduces tax revenues. And if foreign countries retaliate with tariffs of their own, which they did when Trump raised tariffs in his first term, government spending will rise as Washington cushions the blow to affected groups.

My colleague Edward Alden argued in Foreign Policy that Trump intends to run his own trade policy rather than delegate the job to someone else. As Alden summarizes his point: “With a young and relatively inexperienced nominee for [Robert] Lighthizer’s old post of U.S. trade representative (USTR) and an unlikely mix of trade hawks and traditional Republicans in senior economic positions, Trump has left himself firmly in charge of the trade portfolio.” Alden adds that “the issue for Trump’s second term is not the shopworn choice between free trade and protectionism; the free traders have decisively lost that battle in the United States. The question instead is what form protectionism will take in the new administration—and how difficult it will be for trading partners and companies to respond and adapt.”

Alexander Gabuev speculated in Foreign Affairs about how Trump will respond to deepening ties between China and Russia. Gabuev’s guess is that he “might seek to damage the Chinese-Russian partnership by reducing tensions (and even improving ties) with Moscow in order to put pressure on Beijing—something like the reverse of what Secretary of State Henry Kissinger orchestrated more than 50 years ago, when the United States pursued détente with China to exploit the Sino-Soviet split.” Gabuev is understandably pessimistic that such a gambit can succeed. As he notes, Nixon and Kissinger’s opening to China took advantage of a pre-existing rift with the Soviet Union rather than engineered one.

Brian Winter argued in Foreign Affairs that the second Trump administration will make Latin America a priority in U.S. foreign policy. The region, however, may not like the attention. In Winter’s view, “Trump’s policies toward the region are likely to be highly disruptive—and could risk pushing key Latin American countries further away from Washington rather than reversing the drift of recent years.” It is not just Mexico that will feel the pressure: “Other countries, stretching from Guatemala to Colombia, will also face tariffs or other sanctions unless they are seen to be halting the northward flow of migrants through the Darién Gap and other key transit points and taking back citizens swept up in Trump’s promised mass deportations. A second Trump administration will try to pressure Latin American governments including Brazil, Panama, and Peru to stop accepting Chinese investment for sensitive projects such as ports, electric grids, and 5G telecommunications networks.”

Julian Zelizer argued in Foreign Policy that Republican control of Congress means that Trump can make major policy changes even if the Republican margin in the House is “narrow—indeed, the smallest in the in American history.” In Zelizer’s view, “Trump will still have a massive window of opportunity. Although these moments don’t last long, these are the months that offer presidents their most realistic path to legislative achievement of historic significance. Over the next two years, Trump will have the chance to make consequential changes on a number of key policy fronts with congressional approval, including immigration, taxation, and fossil fuel energy production.”

What the Polls Show

A CBS News survey found that six-out-of-ten Americans approve of how Trump his handling the transition. Rubio fared the best among Trump’s foreign policy nominees, with 44 percent saying he is a good choice. In comparison, the choice of Pete Hegseth to be secretary of defense got 33 percent approval, and the choice of Tulsi Gabard to be director of national intelligence got 36 percent approval. That said, in all three cases at least 30 percent of the respondents said they do not know enough about the nominees to have an opinion.

Conversely, an AP/NORC Center poll found that 55 percent of Americans are only slightly or not confident at all in Trump’s ability to appoint well-qualified people to his cabinet. The poll results showed a strong partisan split, with Republicans confident in Trump’s ability and Democrats deeply skeptical.

A poll by the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institution found that the share of Americans who want to see the United States more engaged in the world has risen. The survey, which was conducted after the presidential election, found that 57 percent of Americans favor greater engagement, a fifteen percentage-point increase over what the foundation found in 2023. The support for U.S. engagement abroad carried over to self-identified Trump voters, with six-in-ten of them rejecting an isolationist foreign policy.

Podcasts

My podcast The President’s Inbox is running a special series on Transition 2025. I have spoken with former National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley about the challenges of staffing a new administration; with Steven A. Cook on the challenges that Trump will face in the Middle East; with Christopher M. Tuttle about Trump’s national security team; with Liana Fix and Matthias Matthijs about how Europe is reacting to Trump’s victory; with Will Freeman about what a Trump presidency means for Latin America; and with Sheila Smith with how Japan is reacting to Trump’s return to the White House.

The Election Certification Schedule

Electors meet in each state and the District of Columbia to cast their votes for president and vice president in four days (December 17).

The 119th U.S. Congress is sworn into office in twenty-one days (January 3, 2025)

The U.S. Congress certifies the results of the 2024 presidential election in twenty-four days (January 6, 2025).

Inauguration Day is in thirty-eight days (January 20, 2025)

Oscar Berry assisted in the preparation of this post.