Celebrating Presidents’ Day

The forty-seven presidents of the United States have some interesting stories to tell.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

Monday is Presidents’ Day. For the past fifteen Presidents’ Days, I have recognized the forty-five men—and they have all been men—who have served as president with the following essay, which has been revised over the years. If you are lucky enough to have Monday off, enjoy it.

American kids often say they want to be the president when they grow up. You have to wonder why. True, a few presidents have loved the job. Theodore Roosevelt said, “No president has ever enjoyed himself as much as I have enjoyed myself.”

Most presidents, though, have found the job demanding, perhaps too demanding. James K. Polk pretty much worked himself to exhaustion; he died at the age of fifty-three less than four months after completing his single term in office. Zachary Taylor, the hero of the Mexican American War, found being president harder than leading men into battle. Dwight D. Eisenhower suffered a heart attack and a stroke from the stress of leading the Free World.

Plenty of presidents found life in the White House stifling. Harry S. Truman called it “the great white jail.” Bill Clinton described it as “the crown jewel of the federal penitentiary system.” Barack Obama likened it to living in “a bubble.”

Many presidents also expressed relief once they could be called “former president.” This trend started early. John Adams told his wife Abigail that George Washington looked too happy watching him take the oath of office. “Me–thought I heard him say, ‘Ay, I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which of us will be happiest!’”

Andrew Johnson, who was impeached by the House but acquitted by the Senate, returned to Capitol Hill as a senator from Tennessee six years after leaving the presidency. When an acquaintance mentioned that his new accommodations were smaller than his old ones at the White House, he replied: “But they are more comfortable.” Rutherford B. Hayes longed to escape what he called a “life of bondage, responsibility, and toil.”

The only part of the job that Chester A. Arthur liked was giving parties. He apparently did that quite well. His nickname was the “prince of hospitality.” Grover Cleveland claimed there was “no happier man in the United States” when he lost his reelection bid in 1888. Time away from the White House apparently changed his mind. He ran again in 1892 and won, making him the first, but no longer the only, president to serve two non-consecutive terms. By tradition, non-consecutive terms are counted as separate presidencies. That is why the United States has had forty-seven presidents, but just forty-five men have held the title.

Being president certainly doesn’t spare one from great loss. John Tyler, Benjamin Harrison, and Woodrow Wilson all saw their wives die while they were in office. In Harrison’s case, his wife Caroline died of tuberculosis two weeks before he lost his bid for reelection to Grover Cleveland, the man he had defeated four years earlier. John Adams, Abraham Lincoln, Calvin Coolidge, and John F. Kennedy all lost children during their presidencies. Franklin Pierce’s son and last surviving child was killed in a train accident on the way to his father’s inauguration.

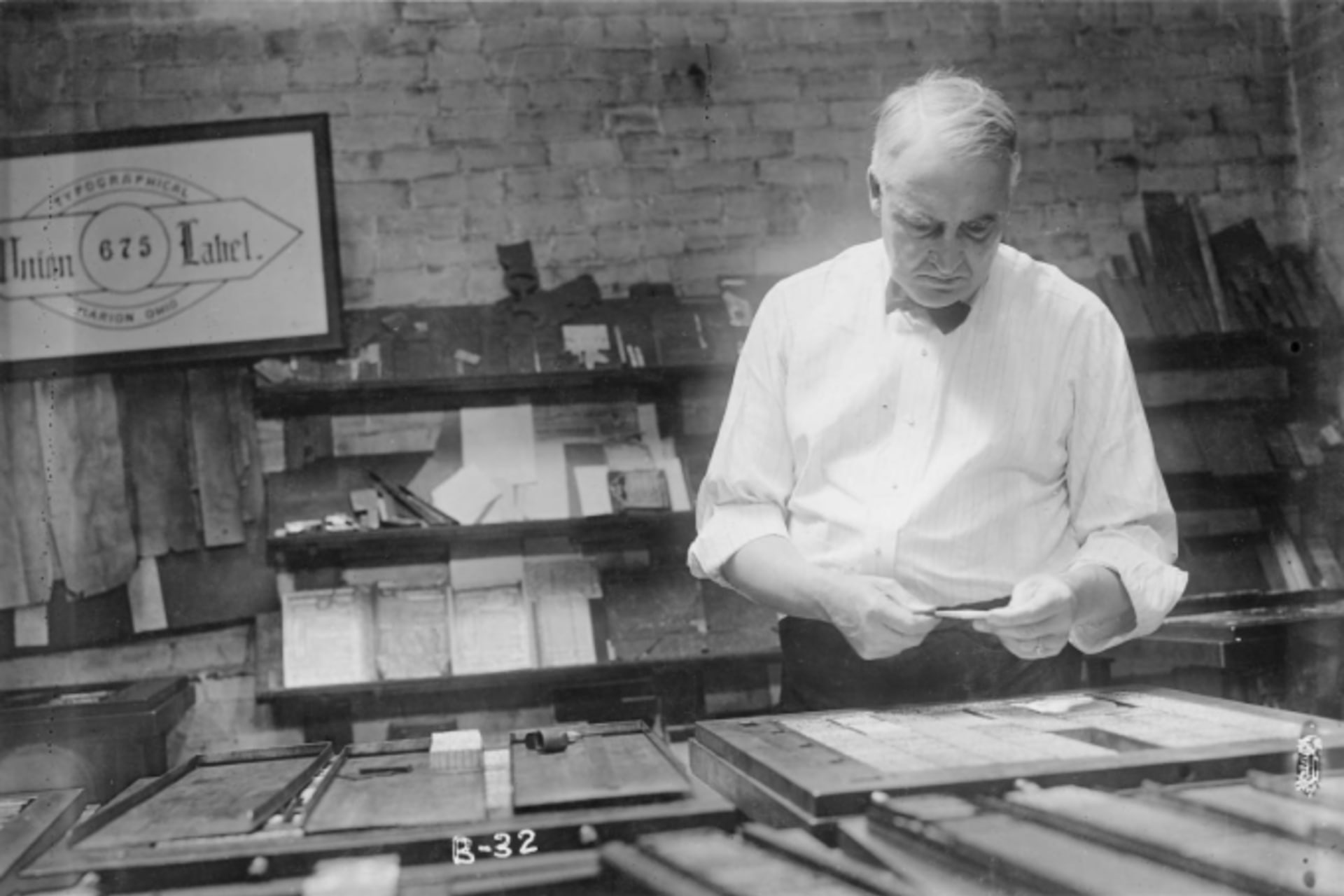

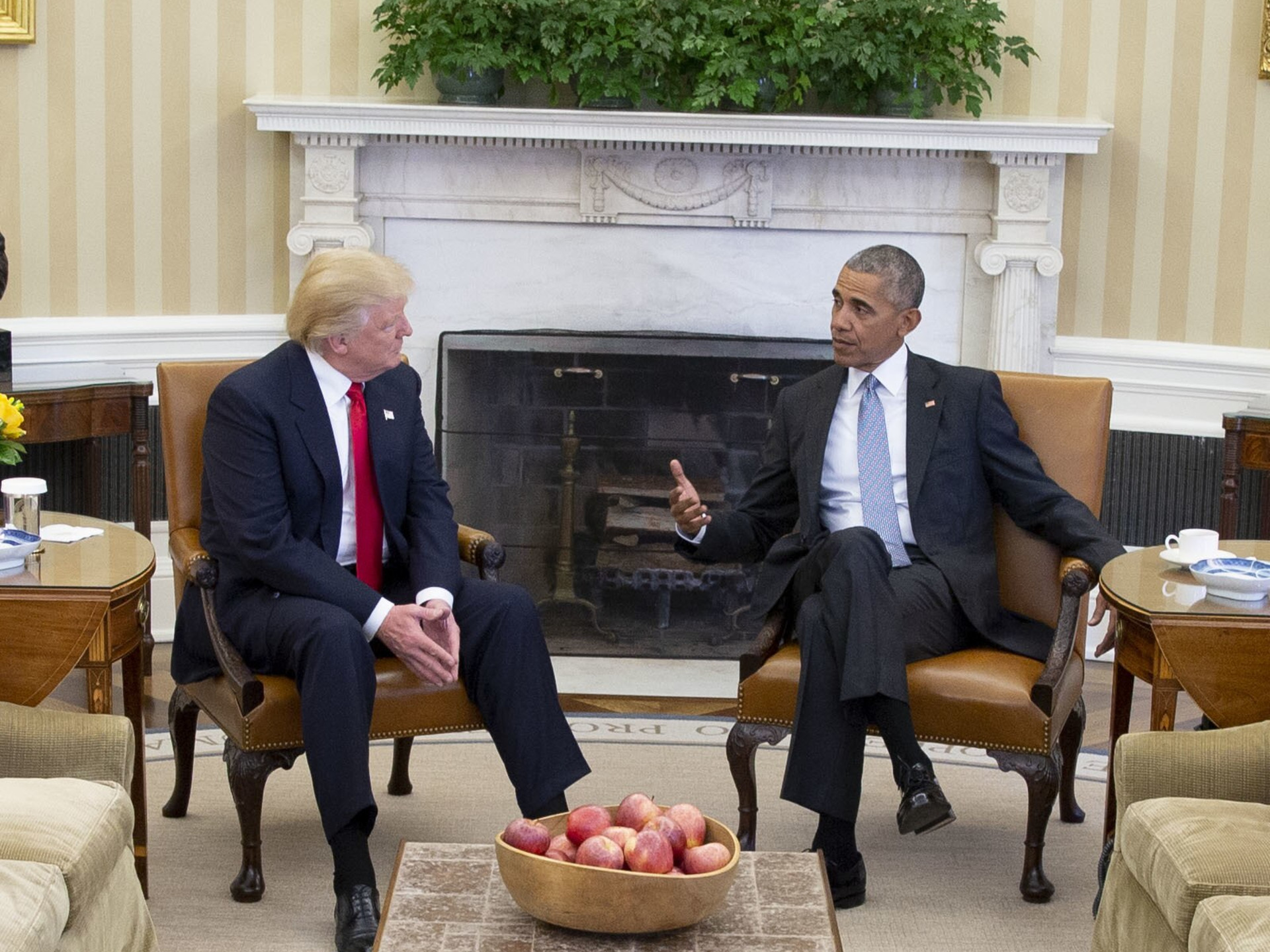

Donald Trump, the only person besides Grover Cleveland to serve two non-consecutive terms in office, blames the media—or “Fake News” as he calls it—for making his job harder than it should be. But complaints about journalists are as old as the Republic. Thomas Jefferson suggested that newspaper editors divide their papers “into four chapters, heading the 1st, Truths. 2d, Probabilities. 3d, Possibilities. 4th, Lies.” Warren G. Harding presumably did not share this sentiment. He is the only president to have had a career in journalism. He owned and served as the publisher of the Marion Star in Marion, Ohio. He did not sell the paper until the third year of his presidency.

The Inaugural Address

An elected president’s first official act is to deliver an inaugural address. The expectations and stakes are high. So high, in fact, that many presidents-elect channel their inner undergraduate, laboring late into the night wordsmithing their remarks. James Garfield, the subject of a terrific Netflix series released last year, didn’t finish his speech until 2:30 a.m. on Inauguration Day. Bill Clinton did him two hours better, fiddling with his speech until 4:30 a.m. Neither speech makes my list of great inaugural addresses.

Some presidents rise to the occasion on Inauguration Day with soaring rhetoric that rings through the ages. Franklin D. Roosevelt gave us: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” John F. Kennedy gave us: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

Alas, most inaugural addresses are forgettable. James Buchanan used his to complain that the country was so consumed debating slavery that it was ignoring more important issues. That address tells us a lot about why Buchanan tops virtually every list of the worst presidents in U.S. history. Ulysses S. Grant, a far better general than president, used his second inaugural address to complain that his critics were treating him unfairly. Most presidents share this sentiment but find better venues to express it.

Richard M. Nixon told his fellow citizens that “the American dream does not come to those who fall asleep.” Uh, okay.

Some presidents get right to the point in their inaugural address. George Washington’s second inaugural address totaled only 135 words—or about the length of two recitations of the Lord’s Prayer.

William Henry Harrison, the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe, went to the other extreme. He took nearly two hours to deliver an 8,000-word speech. Despite the bitterly cold and wet weather, the sixty-eight-year-old Harrison gave his address outdoors without a coat or hat. It was long thought that he caught a cold while speaking, which turned into pneumonia, killing him just a month after taking office. The cause of his death, however, may have been enteric (typhoid) fever that he contracted by drinking contaminated water; the White House at the time drew its water supply just downstream from a sewage dump. Either way, he was the first president to die in office. (His death also made John Tyler the first vice president to finish out a president’s term. For his trouble, Tyler got stuck with the nickname, “His Accidency.”)

William Henry Harrison holds two other distinctions. He was the last American president born as an English subject. And he was the first, and so far only president, to have his grandson become president. Benjamin Harrison, please take a bow.

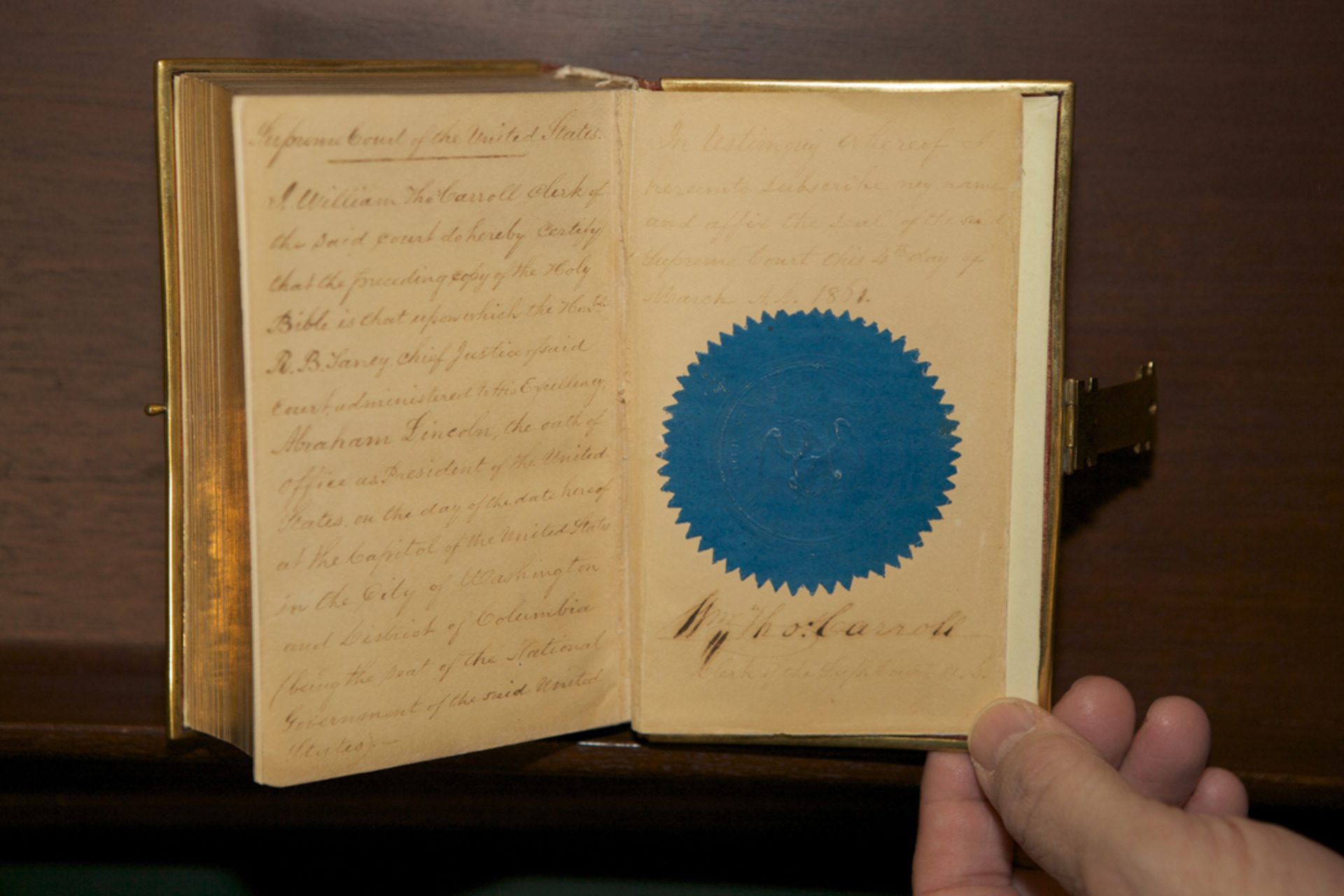

Presidents typically take the oath of office while laying their hand on a Bible. Joe Biden took the oath on a Bible that had been in his family since 1893. In his first inauguration, Barack Obama used the same Bible that Abraham Lincoln used when he was sworn into office for the first time. At his second inauguration, Obama used the Lincoln Bible as well as a Bible that Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. used on his travels.

Donald Trump caused a minor internet stir last year when he failed to place his hand on the Bible during his swearing in. However, the Constitution does not require presidents to swear their oath with their hand on a Bible or on a book at all. Theodore Roosevelt did not use a Bible or any other book when he was sworn in as president in 1901 after the assassination of William McKinley. John Quincy Adams and Franklin Pierce both took the oath of office while placing their hand on a law book.Adams did so to underscore his belief in the separation of church and state. Pierce’s motivation has been attributed to his desire to show his commitment to the rule of law and to his belief that he could not use a Bible because his son’s death showed that God was punishing him for his vanity in seeking the presidency.

Pierce’s inauguration is unique in two respects. First, when he took the oath of office, he began by saying “I solemnly affirm” rather than “I solemnly swear.” The Constitution, which prescribes the words of the inaugural oath, permits both openings. But every other president has started with “I solemnly swear.” The reasons that led Pierce to opt for “affirm” over “swear” have been lost to time. Second, Pierce delivered his inaugural address from memory. That is impressive given that it ran 3,337 words.

Chief Justice John Roberts misstated the oath of office when he swore in Barack Obama in 2009. To ensure that no constitutional issue arose, Roberts administered the oath of office again the following day. January 20, 2013, the start of Obama’s second term, fell on a Sunday. By tradition, presidents are not publicly sworn into office on the Sabbath. As a result, Obama was sworn into office privately on January 20, 2013, and publicly on January 21, 2013. Because of these quirks, Obama can say that he is the only person besides Franklin Roosevelt to take oath of office four times.

When George Washington first took the oath of office in New York City on April 30, 1789, only people within the sound of his voice could hear what he had to say. Every subsequent president until Woodrow Wilson also spoke without the benefit of amplification. Which prompts the question: How many of the people who spent two hours listening to William Henry Harrison drone on in the bitter cold actually heard what he had to say?

Warren G. Harding was the first president to deliver his inaugural address into a microphone. Calvin Coolidge was the first president to deliver his inaugural address over the radio. Harry Truman was the first to deliver his on television. Bill Clinton was the first to do so over the internet.

Changes in technology have been matched by changes in fashion. Today we expect president to wear a suit. However, the first five presidents—George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe—all wore knee britches. John Quincy Adams was the first to wear long pants, so he was a fashionista of sorts.

Whatever presidents wear to their swearing-in, their Inaugural activities can last well into the night. James Madison’s first inauguration in 1809 began the practice of the president and First Lady attending gala balls to thank their supporters. A few presidents, however, have passed on the practice. Franklin Pierce canceled his inaugural ball in 1853 because he was mourning his son’s death. Woodrow Wilson skipped them in 1913 because he disliked their extravagance and expense. Joe Biden had to do without them in 2021 because of Covid.

Some inaugural celebrations have not gone well. Andrew Jackson once threw a party for his well-wishers at the White House that got out of hand. The White House avoided a trashing only when well-wishers were lured out of the mansion with tubs of ice cream and liquor.

The inaugural ball for Ulysses S. Grant’s second term was held in a temporary building that was not adequately heated for what turned out to be a bitterly cold day. Guests danced in their overcoats and canaries that had been brought in to sing for the crowd froze to death.

Landing on Mount Rushmore

All presidents imagine when they take the oath of office that their presidency will be a great one. In an Economist/YouGov poll conducted in 2021, Americans placed Barack Obama atop the list of best presidents, followed by Abraham Lincoln and Donald Trump. A poll run by the same outfit in 2020 also had Barack Obama at number one, but with Donald Trump second and Abraham Lincoln third. Fifteen years ago, Americans said that Ronald Reagan was the greatest president, followed by Abraham Lincoln and Bill Clinton.

Historians and political scientists scoff at these rankings because the public clearly favors recent presidents. That is not surprising. After all, how many Americans know that Millard Fillmore and Rutherford B. Hayes were president let alone have thoughts on their job performance.

The experts typically name George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as the three best presidents, though not necessarily in that order.

Alas, far too many presidents fail to impress either the public or the professionals. The saddest case may be Millard Fillmore. He didn’t even impress his own father, who said that he belonged at home in Buffalo and not in Washington, DC.

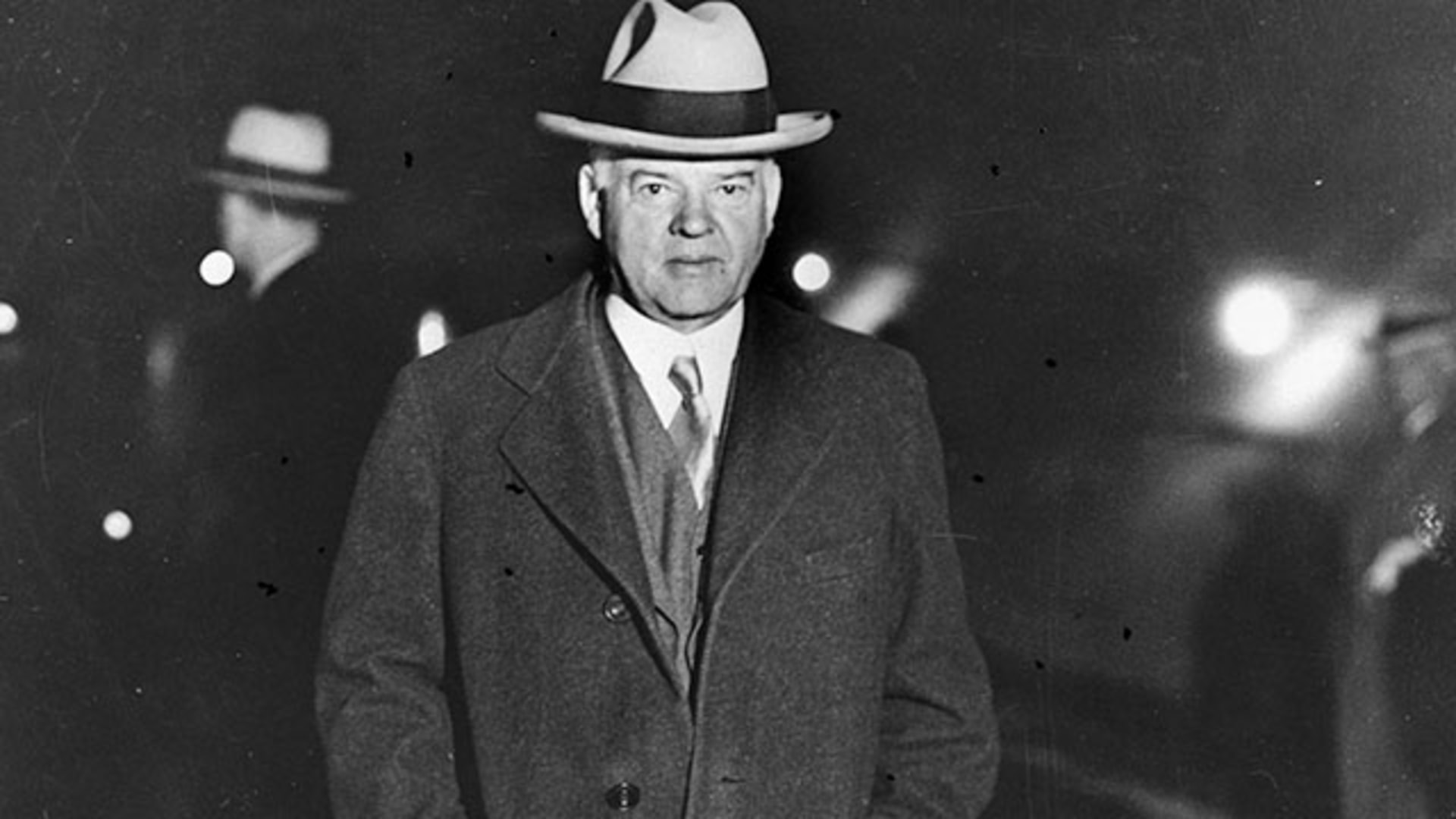

The poster child for presidential failure, however, is Herbert Hoover. He was a golden boy before becoming president. Born in West Branch, Iowa, to humble origins, he was orphaned at a young age. He eventually became a member of the first class to enter Stanford University, where among other accomplishments, he badgered former President Benjamin Harrison into paying the twenty-five cents he owed for admission to a Stanford baseball game. Hoover graduated with a degree in geology, became a mining engineer, lived in Australia and China (where he learned Mandarin Chinese), survived the Boxer Rebellion, and became a wealthy man. During World War I, he entered public service and distinguished himself with his management of the European relief effort after the war ended. A young Franklin Delano Roosevelt marveled that Hoover “is certainly a wonder, and I wish we could make him President of the United States. There couldn’t be a better one.” The irony of that statement, of course, is that FDR ended up running against Hoover for president in 1932 and defeated him. FDR won because Hoover presided over the worst economic collapse in American history. The Great Depression may not have been Hoover’s fault, but he got the blame.

So what does it take for a president to succeed? One key is to be attuned to public opinion. It is perhaps wise, though, not to be as attuned to public opinion as William McKinley. His critics said he kept his ear so close to the ground that it was full of grasshoppers.

A president also needs to know how to work with Congress. Jimmy Carter never mastered that skill, even though his fellow Democrats controlled both the House and Senate. “Carter,” said one lawmaker, “couldn’t get the Pledge of Allegiance through Congress.”

To succeed, a president needs to know when to compromise. The example to follow here isn’t Woodrow Wilson. He once said, “I am sorry for those who disagree with me, because I know they are wrong.” Wilson’s reluctance to compromise led to the demise of his great project, the Treaty of Versailles.

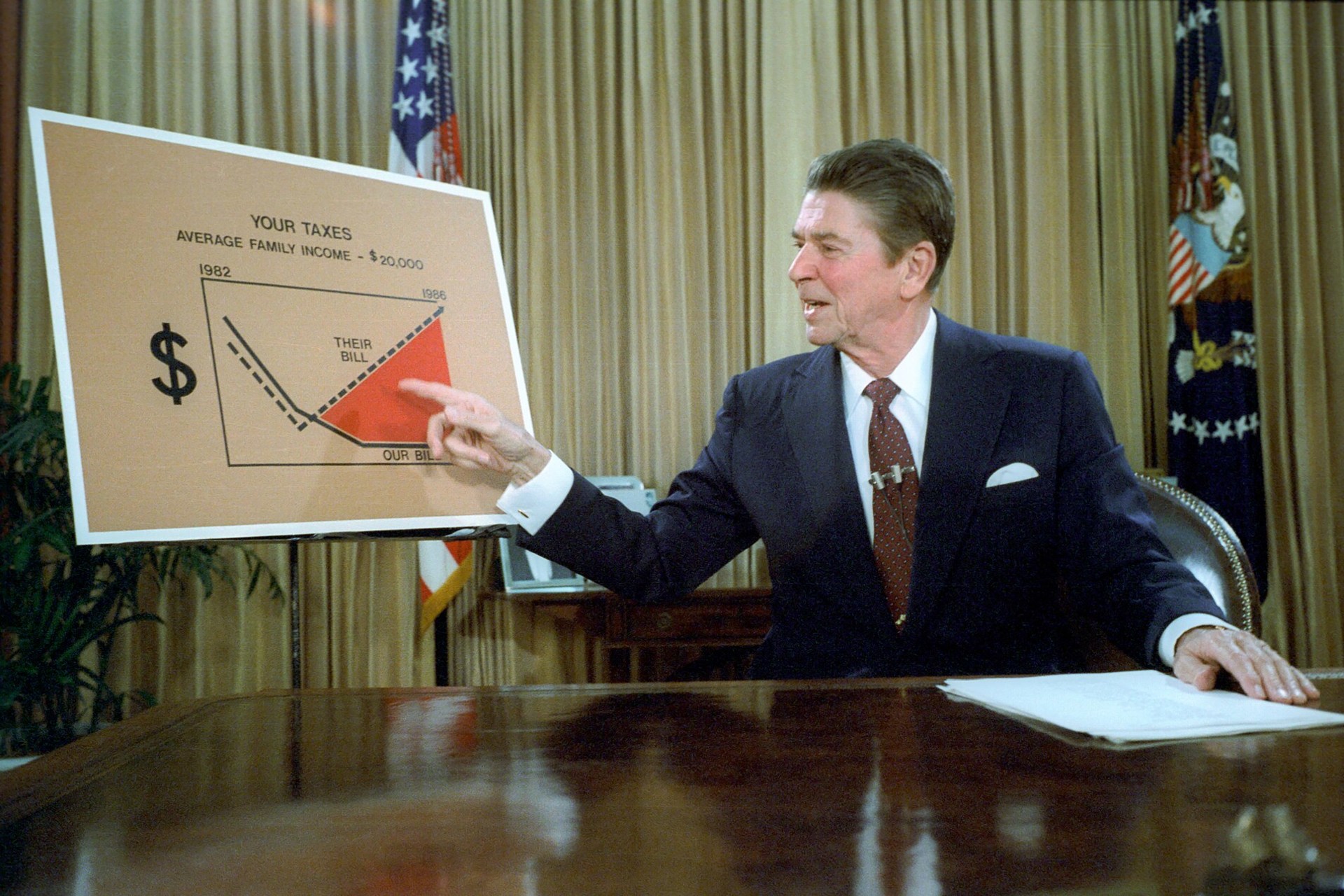

Successful presidents need to know how to say one thing and do another. Republicans hail Ronald Reagan as a tax-cutting, deficit-busting, champion of smaller government. His actual record was different. He signed eleven tax increases into law, saw the national debt more than double on his watch, and left America with a larger federal workforce than the one he inherited from Jimmy Carter. But what people remember him doing matters more than what he actually did.

Presidents should also know how to deal with temperamental cabinet secretaries. Few have faced a harder time than James Monroe. He once had to use a pair of fireplace tongs to fend off his cane-wielding secretary of the Treasury. Monroe also used his sword once to break up a fight at a White House dinner between the French and British ambassadors.

All presidents should be prepared to hit some bumps along the road. As a political science professor once told me, the people love you on the way in, they love you on the way out, and they grumble in between. The difference between the highs and lows can be breathtaking, as George W. Bush discovered. He set the record for both the highest public approval rating and the lowest.

The inherent difficulties of being president and the consequences of failing are no doubt why Joe Biden said of his new job shortly after being sworn in that “I hope to God I live up to it.” To judge by his dismal public approval ratings when he left office, many Americans concluded that he hadn’t.

The Men Who Held the Office

With public popularity a fleeting thing, Harry Truman may have gotten it right when he laid down the cardinal rule of Washington political life: If you want a friend, get a dog. Most presidents have lived by that maxim. At least half of them had dogs. Their dogs’ names have included Sweetlips (Washington), Satan (John Adams), Fido (Lincoln), Grim (Hayes), Veto (Garfield), Stubby (Wilson), Oh Boy (Harding), Fala (FDR), and J. Edgar (LBJ). Donald Trump in 2017 became the first sitting president since fellow Republican William McKinley not to have a dog when he took office. Trump remains pet free on his return to the White House.

Some presidents dare to be different when it comes to companion animals. Andrew Jackson had a parrot named Pol that he taught to swear. Martin Van Buren briefly had two tiger cubs. Benjamin Harrison had opossums named Mr. Reciprocity and Mr. Protection. William McKinley had a parrot named Washington Post. Theodore Roosevelt had his own menagerie, including a garter snake named Emily Spinach, a rat named Jonathan, a macaw named Eli Yale, and a badger named Josiah. Calvin Coolidge apparently wanted to start his own zoo. His pets included a donkey, a black bear, a pygmy hippo, a wallaby, lion cubs, an antelope, raccoons, and a bobcat.

Everyone knows that John F. Kennedy was the first Roman Catholic president, and that Barack Obama was the first African-American president. But neither was the tallest president. Abraham Lincoln holds that distinction at 6’ 4”, with Lyndon B. Johnson just a half inch behind. If you want to win a bet, ask a Republican friend: Who was taller, Ronald Reagan or George H. W. Bush? No, it wasn’t the Gipper.

A fair share of presidents would have strained their necks looking up at Abraham Lincoln. James Madison, the father of the Constitution, is the shortest president. He was 5’ 4”. Martin Van Buren and Benjamin Harrison stand just behind him (above him?) at 5’ 6”. James K. Polk was called “the Napoleon of the stump” and “a short man with a long program.”

The distinction for being the heaviest president goes to William Howard Taft. He weighed between 300 and 350 pounds. He was so heavy that the White House had to install a special bathtub to accommodate his girth. Taft was also the last president to sport facial hair, in his case a handlebar mustache. Being a former president seems to have done wonders for Taft; he lost 80 pounds the year after he left the White House. The weight loss undoubtedly prolonged his life. It also allowed him to enjoy his favorite job —Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He remains the only person ever to have been both president and chief justice. That means he both took the oath of office as president and administered it to a president, in his case to Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover.

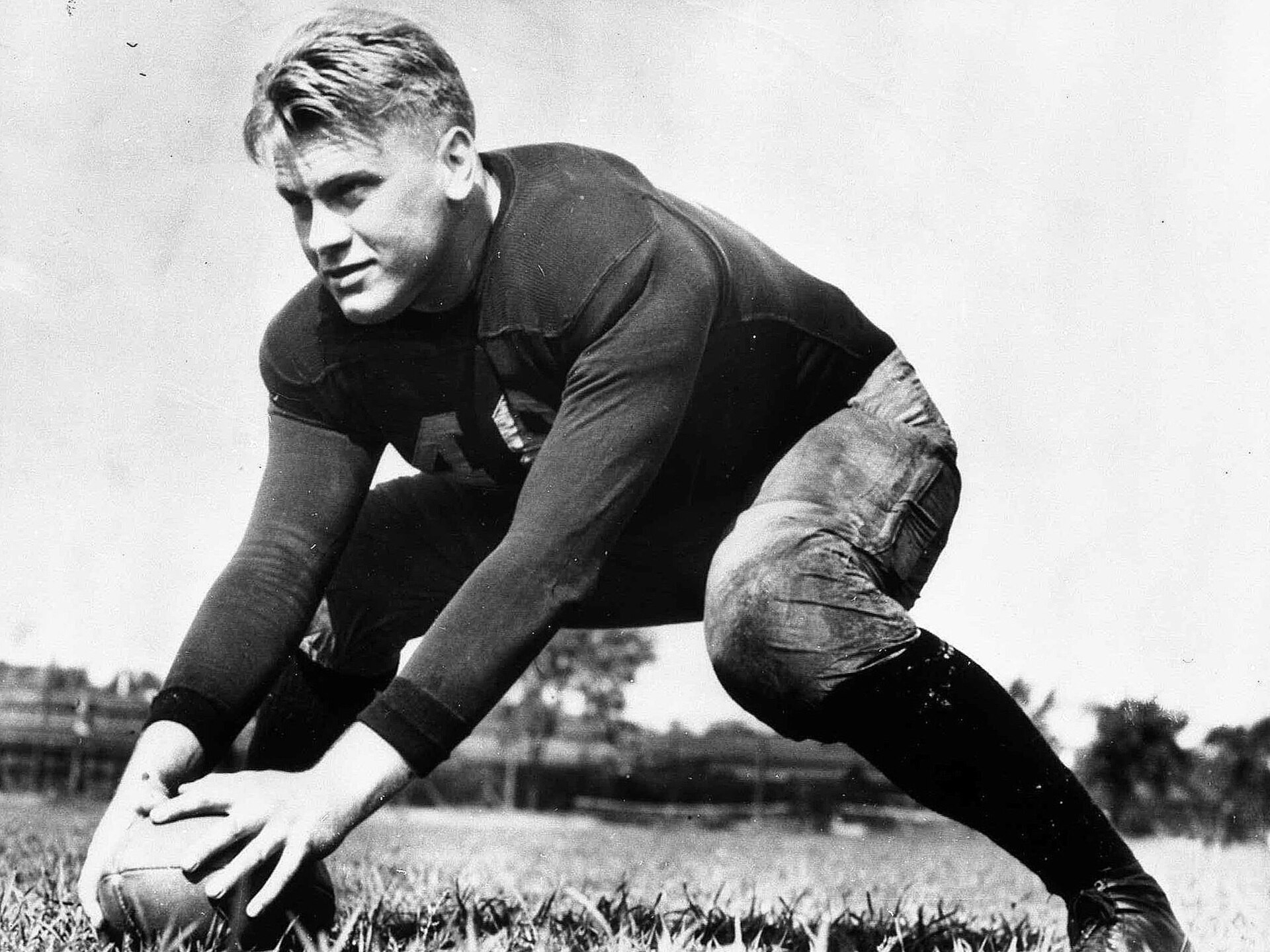

My Favorite

Readers who have read this essay closely know that I have mentioned every president but one: Gerald R. Ford. He holds a unique distinction among the forty-seven presidents of the United States: He was neither elected president nor vice president. He is also the only president to have graduated from a Big Ten university. He attended the University of Michigan, where he played on two national championship football teams and was named the Most Valuable Player his senior year. That alone makes him my official favorite president. Hail to the Victors!

A bibliographic note. Many of the stories in this post come from Paul F. Boller Jr.’s wonderful book, Presidential Anecdotes. It is a great read. His other equally engaging books include: Presidential Campaigns: From George Washington to George W. Bush and Congressional Anecdotes. I highly recommend all three.

Oscar Berry assisted in the preparation of this post.