Remembering the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The United States secured the third-largest territorial acquisition in its history after a U.S. diplomat defied the president who appointed him.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

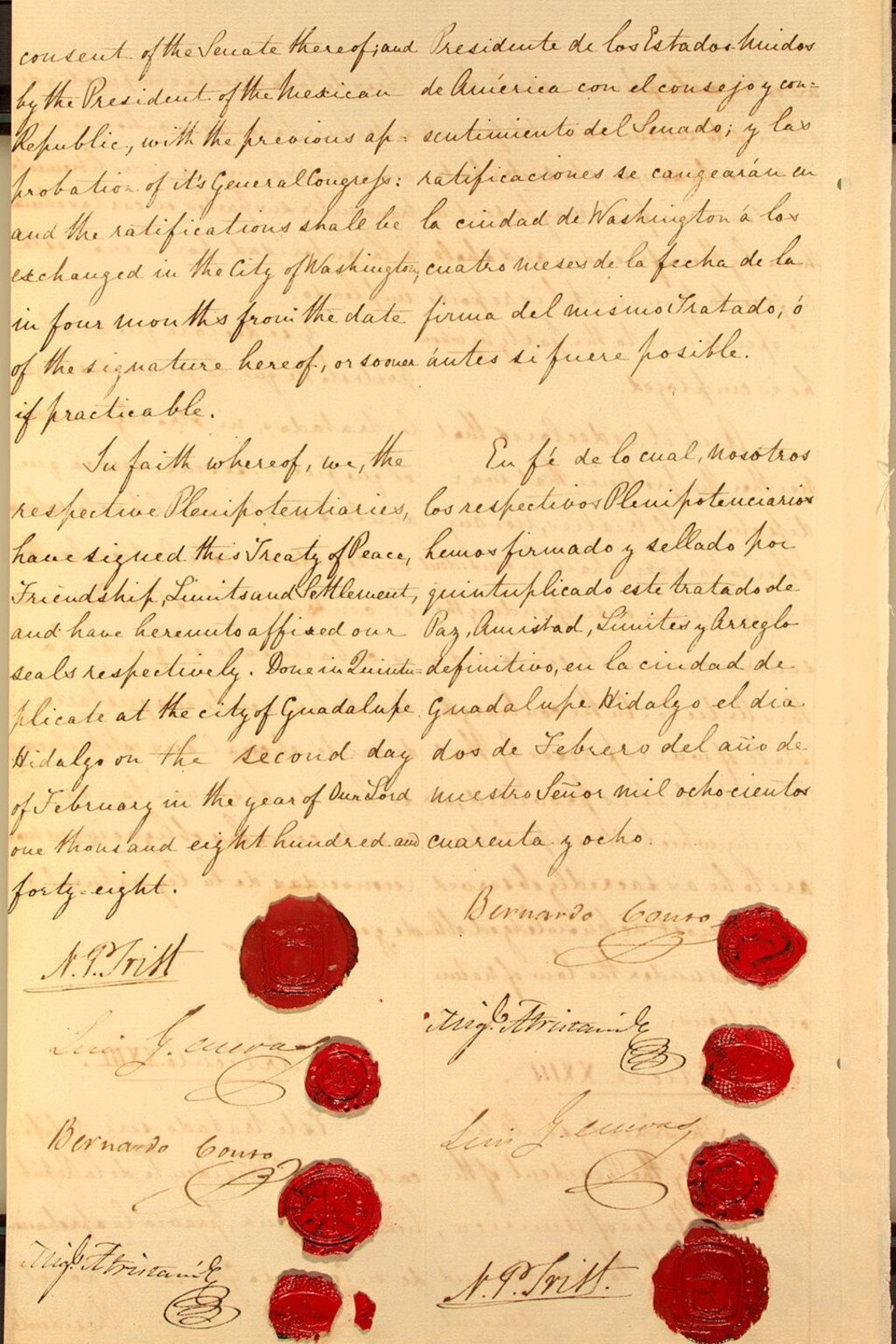

Today marks the 178th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which formally ended the Mexican-American War. The treaty takes its name from the village just north of Mexico City where it was signed. Under the terms of the agreement, the United States took control of what is now the states of California, Nevada, and Utah, most of Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico, and a slice of Wyoming. In return, Mexico received $15 million, and Washington agreed to pay for $3.25 million in financial claims that U.S. citizens had against the Mexican government.

The anniversary is worth noting not just because it is the third largest territorial acquisition in U.S. history, after the Louisiana Purchase and the Alaska Purchase. The anniversary is also significant because the treaty was negotiated by a U.S. diplomat in direct defiance of the president of the United States. Add in a heavy dose of domestic politics, and you have a diplomatic negotiation for the ages.

First, some background. The origins of the Mexican American War are shrouded in controversy; in many ways it was the nineteenth century version of the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. The United States annexed Texas in early March 1845, just days before President James K. Polk took office. The United States and Mexico disputed the location of Texas’s southern border. Polk wanted it set at the Rio Grande, not further north at the Nueces River as the Mexican government had insisted since Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836. Once in office, Polk sent an emissary to Mexico City to settle the border issue and, he hoped, to buy what is today California and New Mexico.

Those talks went nowhere, in large part because Mexico’s weak government could not meet Polk’s demands and survive politically. Then, on April 25, 1846, Mexican troops killed eleven American soldiers just north of the Rio Grande, near what is today Harlingen, Texas. Polk used the clash, which the Americans in some ways provoked, to get through conquest what he could not get at the negotiating table. Once news of the attack reached Washington, Polk’s allies rushed legislation through Congress proclaiming that “a state of war exists” with Mexico, refusing to allow lawmakers who wanted more time and information to speak in opposition.

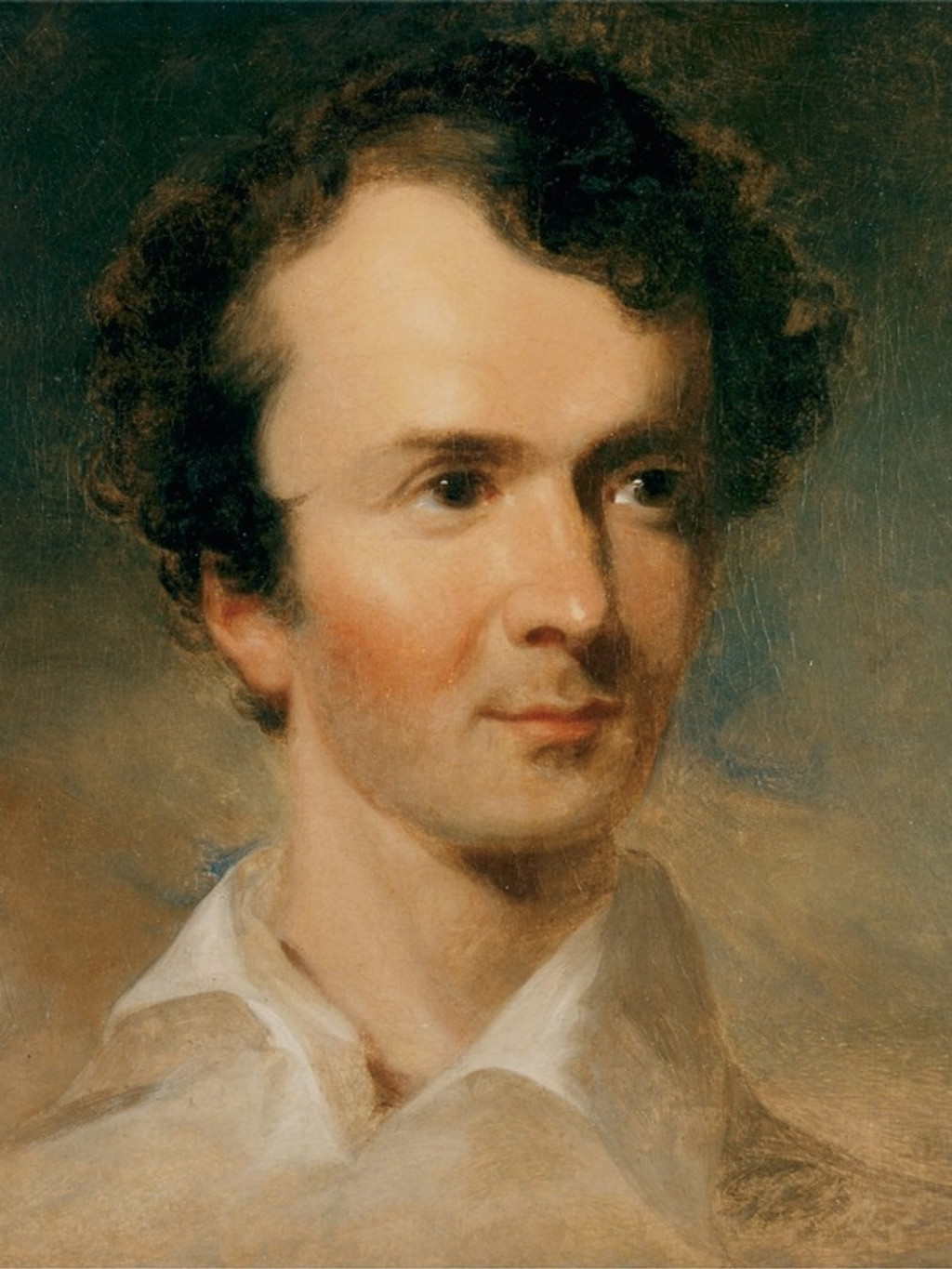

Polk expected a quick victory. He didn’t get it. Despite losing several major battles, the Mexican government, led by Antonio López de Santa Anna, who is best remembered today as the villain at the Battle of the Alamo, refused to negotiate unless U.S. troops left Mexican soil. Polk tried to break the stalemate in the spring of 1847 by sending Nicholas Trist, the State Department’s chief clerk, to Mexico. Trist had once been posted to Havana and knew some Spanish. He was also, like Polk, a Democrat, and presumed to be loyal to the president. Polk particularly wanted Trist to keep an eye on Gen. Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the U.S. Army who personally led an invasion force that landed at Veracruz on Mexico’s Gulf Coast in March 1847 and marched on Mexico City. Polk (rightly) suspected Scott of harboring presidential ambitions.

Trist made little headway over the course of the summer in reaching a deal with the Mexican government. The refusal to meet U.S. demands continued even after Scott’s troops captured Mexico City in mid-September and forced Santa Anna from power.

As the months passed, Polk grew increasingly irritated with Trist. Polk’s primary concern was not that his envoy had failed to conclude a deal with Mexico. It was, instead, that Trist had shown signs that he could not be trusted. One sin was that Trist had forwarded to Washington a Mexican proposal to set the border at the Nueces rather than rejecting the proposal out of hand. Even worse, Trist had struck up a friendship with Scott. So in early October, Polk ordered Trist to return to Washington.

Trist received his recall in mid-November. He responded by doing the unthinkable: He continued negotiating. He believed that if given more time the new Mexican government would meet Polk’s terms. Trist also worried that if he returned home that the next U.S. envoy might ask for even more from Mexico. He thought that tougher terms would be unacceptable to the Mexicans and condemn the United States to a protracted guerrilla war. As he later explained it:

My object was…to make the treaty as little exacting from Mexico, as was compatible with its being accepted at home.

So, Trist sent Polk a sixty-five-page letter explaining why he was ignoring his recall. The letter reached Washington in mid-January. Polk did not take the news well. He wrote in his diary that the letter

is the most extraordinary document I have ever heard from a Diplomatic Representative . . . . His despatch is arrogant, impudent, and very insulting to his Government, and even personally offensive to the President. He admits he is acting without authority and in violation of the positive order recalling him. It is manifest to me that he has become the tool of Gen’l Scott and his menial instrument, and that the paper was written at Scott’s instance and dictation. I have neer in my life felt so indignant, and the whole Cabinet expressed themselves as I felt …. If there was any legal provision for his punishment he ought to be severely handled. He has acted worse than any man in public employ whom I have ever known. His despatch proves that he is destitute of honour or principle, and that he has proved himself to be a very base man.

While the president fumed back in Washington, Trist concluded the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The treaty gave Polk everything he had asked for in his original instructions to Trist. That, however, did not satisfy the president. His territorial ambitions had grown with the capture of Mexico City. He wanted to squeeze more land out of the Mexican Government.

But Polk now had a political problem. Public opposition to what critics called “Mr. Polk’s War” had been mounting. In late December 1847, an obscure Illinois congressman named Abraham Lincoln had offered the so called Spot Resolution demanding to know exactly where on U.S. soil the first American blood had been shed in 1846. Two weeks later, the House passed a resolution declaring that the war had been “unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun.” (The Senate never took up the House motion.)

The opposition to the war partly reflected the failure of U.S. troops to secure a quick victory. But the opposition also reflected opposition to slavery and the racist views many Americans held of their neighbors to the south. Abolitionists argued that the conquest of Mexico would lead to slavery’s expansion. Their supporters in Congress repeatedly introduced, though they failed to pass, the Wilmot Proviso, which would have barred slavery in any territory taken from Mexico. Meanwhile, many Americans only wanted Mexican territory if it was sparsely populated. They believed, as one writer of the era put it, that “Spanish blood will not mix well with the Yankee.”

Polk knew he was boxed in. As he summarized his dilemma for his cabinet:

If I were now to reject a treaty made upon my own terms, as authorized in April last, with the unanimous approbation of the Cabinet, the probability is that Congress would not grant either men or money to prosecute the war.

Should that happen, the United States might lose the less territory it stood to gain under the treaty that Trist had negotiated. Rather than test his prediction about what Congress would do, Polk submitted the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to the Senate on February 22. Less than three weeks later, the Senate provided its consent.

Although Polk did not achieve his maximalist demands, he did exact revenge on Trist. Polk refused to pay Trist’s salary or reimburse him for the expenses he incurred while in Mexico. Trist lost his State Department job, plunging him into poverty. He had to wait nearly two decades before Congress reimbursed him for his lost salary and unpaid expenses. President Ulysses S. Grant, who fought with great distinction in the Mexican-American War and thought it was “the most unjust war ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation,” made him postmaster of Alexandria, Virginia, just across the Potomac River from Washington.

The United States celebrates its 250th anniversary in 2026. To mark that milestone, I am resurfacing essays I have written over the years about major events in U.S. foreign policy. A version of this essay was published on February 2, 2011.

Oscar Berry assisted in the preparation of this post.