The North American Market: A Competitive Edge That Shouldn't Be Squandered

More on:

If there’s a golden rule for economic competitiveness, it's this: “Always exploit your advantages.” Yet for more than a decade, the United States has systematically undermined one of its biggest – our proximity to a wealthy, resource-rich partner to the north and a developing, labor-rich partner to the south.

Robert Pastor’s fine recent book The North American Idea, makes a compelling case that the strong U.S. economic growth of the 1990s was directly linked to growing economic integration with Canada and Mexico, and that the weak growth of past decade is in no small part the result of disintegration, brought about largely by unwarranted fears over NAFTA and the unfortunate U.S. response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Two documents released this week drive that home. The first is a paper by Erik Lee of the North American Center for Transborder Studies and Christopher E. Wilson of the Woodrow Wilson Institute called “The State of Trade, Competitiveness and Economic Well-being in the U.S.-Mexico Border Region.” It lays out succinctly the benefits of what is essentially a joint production system between the two countries in sectors like automobiles, aerospace, and medical devices, with a supply chain that straddles the border. Cross-border production has allowed for more efficient location of business activities in ways that enhance productivity, lower costs, and help North American-based companies to compete more effectively with Asia and Europe.

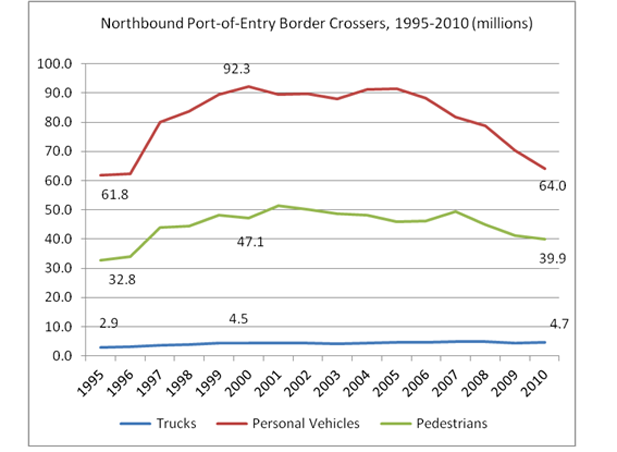

Over the past decade, however, that deep integration has become considerably shallower. From 1993 to 2000 bilateral trade grew at 17 percent annually; from 2000-2008 it grew at just 4.5 percent. Some of this was the impact of China, which became increasingly attractive as a platform for exports to the United States. But a big factor was the hardening of the border that occurred after 9/11. Northbound car traffic has fallen by one-third since 2000, and truck traffic has barely grown. And even as the Border Patrol doubled in size to discourage illegal immigration, few inspectors were added at the ports of entry to help commerce and lawful travel. While estimates vary, increased border restrictions and the resulting congestion has cost the U.S. economy tens of billions of dollars annually, and almost certainly pushed some production out of North America.

Chart Source: "The State of Trade, Competitiveness and Economic Well-being in the U.S.-Mexico Border Region"

The second document is the new “Northern Border Strategy” prepared by the Department of Homeland Security. The economic story at the northern border is broadly similar to the southern border. U.S.-Canada trade flows recovered more quickly after 9/11, but were also hampered by rising border costs and delays. Economic research suggests that U.S.-Canada trade volumes from 2000 to 2007 were about 12 percent below what would have been expected given economic growth and exchange rates. The costs for complying with new border requirements have been estimated to add 3 to 4 percent to the cost of cross-border trade, weakening the North American advantage vis-à-vis Asia and Europe.

The new DHS strategy makes all the right noises about promoting both growth and security, and strongly endorses the U.S.-Canada Beyond the Border initiative, a promising government-to-government effort to strengthen security and enhance trade and cross-border travel through much closer cooperation between the two countries. Encouragingly, the DHS strategy calls for new performance measures that focus more clearly on assessing the efficiency of border crossings.

While the threat of terrorist attacks remains real, it can never be repeated too many times that the 9/11 terrorists did not enter the United States from either Canada or Mexico. Terrorism is also, as my CFR colleague Micah Zenko nicely highlighted this week, a rather low probability threat in North America (as he drily notes: “the number of U.S. citizens who died in terrorist attacks increased by two between 2010 and 2011; overall, a comparable number of Americans are crushed to death by their televisions or furniture each year”). In contrast, the current unemployment rate of 8.2 percent, and a real rate that is probably double that, is a serious threat to the well-being of millions of Americans.

With some multinational companies rethinking their China strategies in the face of rising costs and regulatory obstacles, the United States has a real opportunity to attract more business and create badly-needed jobs. A seamless continental market would strongly reinforce that encouraging trend.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store