Not putting your money where your mouth is

More on:

In March, China’s premier expressed concern about the safety of China’s (large) investment in the US, including China’s investment in Treasuries. China’s citizens have realized -- rather belatedly -- the risks associated with holding more reserves than China really needs.*

And some in Japan are also now starting to worry about the safety of Japan’s dollar-denominated Treasuries.

You might think -- based on all this chatter -- that central bank demand for US Treasuries has waned.

It hasn’t.

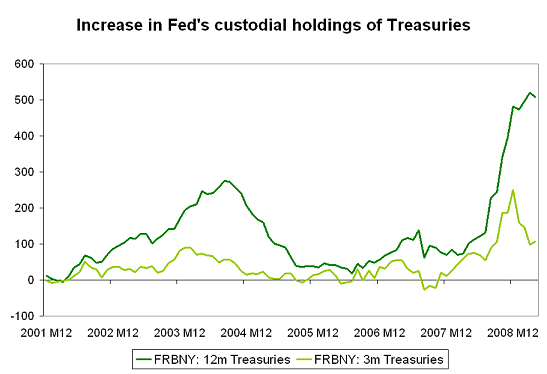

Central bank holdings of Treasuries at the New York Fed have increased by over $500 billion over the last 12 months. Central bank purchases in the 12ms through March set an all-time record - and purchases in the 12ms through April are only a bit lower.

Central bank holdings of Treasuries at the New York Fed rose by close to $100 billion in the first quarter of 2009. That is down from the $250 billion increase in the fourth quarter of 2008, but it had to fall from that pace: $ 1 trillion in annualized Treasury purchases is rather hard to sustain when central bank reserves are falling. The $100 billion central bank added to their Treasury portfolio at the Federal Reserve over the last three months of data is still more than central banks bought in late 2003 and early 2004 - a time when Japan was buying what then seemed like huge quantities of Treasuries.

Indeed, the rise in central banks’ Treasury holdings over the last 6 months is far larger than can be explained by the (non-existent) growth in central bank reserves. It reflects a shift out of Agencies -- and (less discussed) a shift out of large deposits in the major international banks. Treasuries aren’t free of all risk, but central bank reserve managers have concluded that they are less risky than other dollar-denominated reserve assets.

The pace of outflows from the Agency market is a warning against too much complacency on the United States part. If central bank reserve managers do lose confidence in an asset, they can go from buying large sums to selling large sums quite rapidly. Confidence is a mysterious thing. Reserve managers stopped buying Agencies rather suddenly; there wasn’t much advance warning. The fact that most most recent central bank inflows have gone into short-term bills is also a signal of sorts. Central banks either are desperate for the most liquid asset of all -- or they haven’t been comfortable buying lots of ten-year dollar-denominated notes at yields under 3% and risking mark-to-market losses if Treasury yields eventually rise.

At the same time, most reserve managers worry far more the risk of visible losses, especially credit losses, than about returns. They also need to make sure that they hold enough truly liquid assets to cover their countries immediate needs in a crisis. Right now most central banks seem to be more worried about the risk that they will find themselves with too few liquid US Treasuries rather than the risk that they will hold too many.

Indeed, it isn’t inconceivable that if the gap between the yield on short-term bills and longer-term notes gets large enough, credit-risk adverse reserve managers who want a bit more yield will shift out of bills and into longer-term notes. Central banks do need some income. And they are more comfortable taking interest rate risk than credit risk. Optics.

All the talk about the risks of holding Treasuries, central bank demand for Treasuries also has held up far better than central bank demand for almost any other asset. Central bank demand for Treasuries hasn’t grown as fast as new issuance. Indeed, for the first time in years, central bank reserve managers aren’t absorbing the majority of the Treasury’s new paper. But that is entirely a function of the huge size of the US Treasury’s borrowing need, not a function of any fall in central bank demand.

And in some sense it is strange that the major central banks haven’t publicly talked about the risks of the assets that they are selling, while the national leaders of a few key countries with big reserve portfolios have publicly discussed the risks of the assets that they are buying ...

* The usual argument is that the US will inflate away the value of China’s Treasuries. That argument clearly puts blame for any fall in the value of China’s Treasury holdings on US policy makers. The bigger risk though is that the dollar will fall against China’s currency, reducing the CNY value of China’s external portfolio. That fall could happen even if inflation in the US never picks up, as there are strong fundamental reasons to think that renminbi should rise over time against the dollar -- and, for that matter, the euro. However, it is far harder to attribute losses from currency moves to bad US policy -- as China’s leaders opted to build up their dollar reserves in order to keep China’s currency from rising. That policy helped China’s exporters, but it also exposed China’s taxpayers to the risk of future losses -- as they were effectively "over-paying" for dollar reserves that China didn’t need for its own financial stability.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store