The Iraq Data Debate: Civilian Casualties from 2006 to 2007

Published

Updated

Gen. David Petraeus’ assertions about falling casualties in Iraq are supported by a range of objective sources. But his testimony to Congress does not establish whether the decline is attributable to the surge or to sectarian cleansing.

This publication is now archived.

Introduction

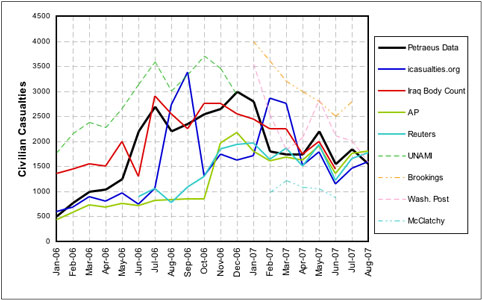

There is a growing debate over the data used to support claims of progress in Iraq. In particular, it has been widely asserted that Gen. David Petraeus and MNF-I (Multi-National Force-Iraq) have produced artificially optimistic data on civilian casualties. Petraeus has argued that civilian fatalities climbed over the course of 2006, but fell forty-five percent over the last eight months as surge brigades have arrived in Iraq. [1] These findings have been challenged on a variety of grounds. Some accept the observation that casualties have declined, but argue that much of this is due to sectarian cleansing rather than improved security: where the intended targets have already been driven out, violence becomes unnecessary but the neighborhood is no more secure for targeted minorities. [2] But others dispute the observation of decline itself. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, Spencer Ackerman of the American Prospect, and John Podesta, Lawrence Korb, and Brian Katulis of the Center for American Progress, for example, argue that violence is not falling. National security expert Rand Beers argues that claims of a decrease cannot be verified by independent sources. [3]

Iraq data are inherently messy and all empirical claims need to be treated with caution. But two broad points seem clear nonetheless. First, sectarian cleansing is an important factor in Iraq ’s violence, but it is hard to know how important it has been relative to the surge in reducing civilian casualties. No claim for the relative importance of the surge and cleansing for Iraqi civilian casualties can be sustained from available data. Second, MNF-I is not alone in finding a reduction in civilian deaths since 2006. Multiple, independent sources find similar trends, and there is very little evidence to suggest any upward trend in violence in 2007. Given this, the Petraeus testimony is not inaccurate or uncorroborated in the way many have claimed. But neither is it complete: while the testimony does not explicitly attribute the casualty reduction to the surge as opposed to sectarian cleansing or other causes, its weight of emphasis implies a primary role for the surge. A more complete assessment would have addressed potential alternative causes explicitly, and would have clarified the limitations on what can be known about the surge’s effects.

Figure 1*

Sectarian cleansing’s unknown contribution to casualties

There has clearly been a great deal of sectarian cleansing in Iraq, and cleansed neighborhoods are presumably harder for hostile militias to penetrate for murder or bombing attacks than mixed ones. Homogeneous neighborhoods may thus be safer than mixed ones (though imperfectly: Sadr City has been overwhelmingly Shiite since before 2003, but has been a frequent target of Sunni bombings all the same). But this does not necessarily mean that overall casualties will fall as neighborhoods within a city are cleansed.

The most violent districts are often those at the frontiers, where cleansing is actively underway. As neighborhoods are cleansed, these frontiers move on to the next block, but this merely moves the fighting; it does not end it. Eventually this process can indeed yield a cruel form of peace between sects within a given city, but only when that city as a whole becomes uniformly Shiite, Sunni, or Kurd (which Baghdad, for example, is still not). Even this need not end intra-sectarian violence, hence its impact on overall civilian casualties is unclear. And it is far from clear that cleansing even a particular city ends inter-sectarian violence nationally: Iraqi militias have shown a willingness to travel between cities and towns to expand their scope well beyond the borders of any one locality, hence a cleansed town may only lead to the opening of new violence in the next community until the process exhausts the country or is halted by security forces.

These moving frontiers of sectarian violence thus clearly change the geography of civilian deaths, but may or may not change their numbers very much. Hence the role and importance of cleansing for Iraqi civilian casualty trends are unclear. And in parallel with this cleansing effort has been the gradual arrival of the surge forces and their increasing use in direct population security—not to mention other effects, such as Muqtada al-Sadr’s decision to order his militia to stand down as the surge was announced in early 2007, or the decision by Sunni Sheiks in Anbar Province to stop fighting Americans and turn on al-Qaeda in Iraq instead (which has now radically reduced AQI’s lethality in Anbar). The relative causal role of these events cannot be parsed very accurately on the basis of publicly available information. Given this, about the most that can be said is that some unknown mix of improved security, voluntary decisions by key militias to stop fighting, a changing scope of internecine violence as cleansing frontiers have shifted, or still other factors collectively explain any change in civilian casualties. This leaves open the possibility that improved security was the chief cause—or that it was a smaller contributor than the others.

Petraeus’ statement did not discuss the potential role of sectariancleansing in Iraqi civilian casualty trends. [4] It should have. An explicit discussion would have provided a more comprehensive picture, and reduced the risk that the testimony could mislead its audience by overlooking competing explanations of the identified trends. But it should be noted that Petraeus did not actually claim that security alone explains reduced casualties. On the contrary, his statement consistently frames the surge as “one reason” for the observed decline in violence, and he consistently describes it as “helping reduce” the violence. This formulation clearly implies other contributors beyond the surge, and carefully avoids unique causal attribution that the data could not sustain. And a thirty-three percent increase in U.S. combat brigades designed to provide direct population security in Iraq surely had some effect on civilian casualties. Gen. Petraeus’ statement was thus incomplete, and potentially misleading in its emphasis, but not inaccurate as such. [5]

The pattern of declining casualties

As for the second point, most available independent data sources show a broad pattern similar to that asserted by MNF-I: civilian casualties increase until some point near the end of 2006; this trend changes in 2007 and casualties then decline. Figure 1 presents these data graphically. [6]

Unsurprisingly, the data are noisy. It is very difficult to collect complete, accurate figures on deaths in Iraq: reporting is haphazard; communications are difficult; many sources (such as hospital officials) are under threat by sectarian militia or insurgents and face pressure to manipulate data; Muslim burial customs encourage very rapid interment by immediate family, complicating casualty reporting; other bodies are discovered, if at all, only long after the killings took place, obscuring the date of the actual murders. No two sources thus agree completely, and the differences can be large—over two thousand five-hundred deaths separate the highest (3,389, according to icasualties.org) from the lowest (842 from AP) figure for September of 2006, for example.

But although there is disagreement on individual months’ totals, the trend in the data as a whole is quite similar across sources. All sources with data for 2006 show civilian casualties increasing for the year, often quite sharply (icasualties.org, for example, presents a five hundred-seventy percent increase for the year; AP reports a five hundred-ten percent rise), and all of these display a maximum value in late 2006 (in September for icasualties.org, for example; December for AP; November for UNAMI). All sources with data for 2007 and 2006 show a net decline in 2007 from the 2006 peak. The 2007 decline is sometimes steep (IBC, icasualties.org, or Washington Post), and sometimes shallow (AP or Reuters), but with the sole exception of McClatchy (which has no 2006 data), all others show some apparent decline for the year in 2007. Neither the increase nor the decrease is uniform: values fluctuate up and down from month to month as well as across sources. And most sources (all but AP and Reuters) show a double peak, with local crests in the vicinity of July-September 2006 and again somewhere between the following October and February. One, AP, shows a trend in the latter months of 2007 that is essentially flat. But the high value in all five series occurs somewhere between July and December 2006, with no value in 2007 equaling that source’s 2006 maximum, and with all displaying a downward slope for 2007 as a whole.

Nothing in these data suggests that MNF-I is an unreasonable outlier contradicted by all other sources. In eighteen of the twenty months presented, the MNF-I figure is between the high and low values presented by other sources. The MNF-I pattern of increasing casualties in 2006 followed by decreasing casualties in 2007 is consistent with the broad trends in the available data as a whole. MNF-I’s data show steeper slopes than some sources, but less steep than others: while the MNF-I rate of increase for 2006 is the sharpest of the available sources, its rate of decline for 2007 is exceeded by icasualties.org, IBC, the Washington Post, and Brookings. [7] On balance, MNF-I’s casualty totals for 2006 are slightly higher than the mean for the other data sources available (by about four percent), and slightly lower for 2007 (also by about four percent), but the differences are small. It is hard to sustain a claim that MNF-I is radically out of step with other, independent, data sources, or that those sources contradict MNF-I in any substantial way—if one considers the data as a whole, rather than focusing on selective subsets taken out of context.

The use and misuse of data

But if one is willing to take selective subsets out of context, then it is possible, in fact, to support any conclusion from these data. This is because the data are noisy and non-monotonic: values rise, then they fall, and both the rise and the fall are subject to apparently random fluctuations from month to month along the way. A misleading two-point comparison can thus easily be structured to imply that casualties are getting worse, not better, in 2007; or that the drop in 2007 is much greater than it is; or that there has been no change at all. If one chooses July and August of 2007, for example, then casualties go down for the MNF-I and Washington Post data, but they go up, during the surge period, for the AP, Reuters, and icasualties.org data (and all but the Washington Post data show a twenty to thirty-five percent one-month increase for June to July 2007, including MNF-I). But this is at least as likely to be an artifact of month-to-month instability as a sign of an underlying real reversal of security: much as the stock market bumps up and down even in the midst of long term trends to the contrary, so do these data, and the clear trend for 2007 as a whole is down.

Alternatively, many have compared 2007 data with figures for the same month from 2006; in each case, the 2007 figures are higher. But this hardly means that casualties are now increasing—on the contrary, the slope is now downward for all sources save the latter months of AP. The downward slope for 2007 is shallower than the upward slope for 2006, hence comparisons separated by twelve-month spans will show that the later values have not yet declined to the earlier levels. But if the current trend continues, they will. And there is nothing magic about twelve-month intervals; if one compares casualties at quarterly intervals, for example, the later values are generally lower than the earlier ones for 2007, not higher. For cyclic businesses in the civil economy, twelve-month comparisons are important because they compare like quantities (Christmas season sales this year and last year, for example). But there is no reason to suppose that Iraq is a seasonally cyclic business, hence there is no special significance to same-month comparisons per se.

None of this means that current strategy will necessarily succeed or that current policy is necessarily sound. These trends could flatten out or reverse in coming months. The up-tick in some sources for July or August 2007 could eventually prove to have been the beginning of a new and unfortunate long-term trend if they continue in this direction rather than bumping back downward again. And even if favorable casualty trends continue, at the current rate of decline they have a long way to go before they reach tolerable levels: even at the current rate of decline, it will take a year for casualties to fall even to five-hundred a month. One of us has argued that total withdrawal is a defensible option for Iraq, [8] and these data do not suffice to overturn such a finding; a much deeper analysis is required to sustain any particular position on the war. There is plenty of room for debate on US policy in Iraq . But not all assertions about casualty trends are defensible. And the frequent assertion that MNF-I’s data are unrepresentative is unsound.

*In Figure 1, Iraq Body Count (IBC) data for June 2006 was entered incorrectly as 1300. The correct value is 2352. Data shown for IBC, downloaded on September 14, 2007, are averages of the “high” and “low” values for each month.

Note on the authors

Stephen Biddle is Senior Fellow for Defense Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations and served as an advisor to General Petraeus in Baghdad in spring 2007. The views expressed here are his own. Jeffrey Friedman is Research Associate at CFR.t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- Jeffrey Friedman