How a Treaty With France Helped Secure American Independence

The Continental Congress’s success in negotiating a military alliance with France was pivotal to the colonies’ successful effort to overthrow British rule.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

President Donald Trump’s repeated criticisms of U.S. allies tap into a longstanding vein of doubt in American political thinking about the value of alliances. President George Washington famously argued in his Farewell Address that “the great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible.” President Thomas Jefferson used his first inaugural address to call for “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none.” The United States entered World War I as an “associated” rather than an “allied” power, a nod to its more than century-long practice of not linking its fate to the fates of others.

This skepticism of alliances comes with a healthy dose of irony. If the thirteen colonies had not signed the Treaty of Alliance with France on February 6, 1778, the American Revolution might have failed, and United States might not exist.

Rebels Need Allies

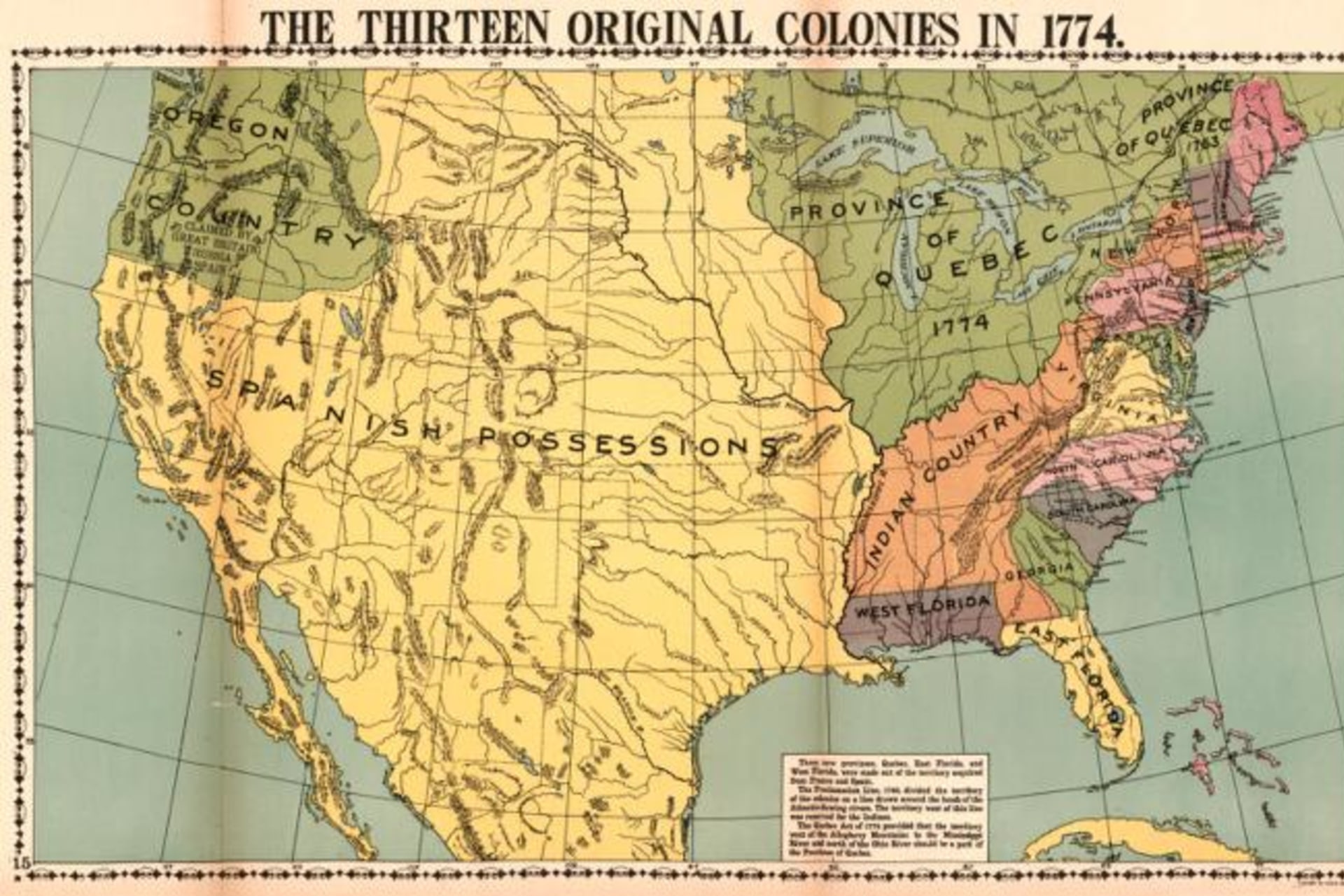

The Continental Congress’s decision to declare independence from Great Britain was a high-risk gamble. Britain was the world’s dominant power. Just thirteen years earlier it had defeated France in the Seven Years’ War, or what the colonists called the French and Indian War, driving the French out of North America. If a major European power could not defeat Britain, how could the thirteen colonies? Possessing only a ragtag army and no real navy, the colonists knew they needed allies.

The obvious choice was France, the country that many colonists had fought just a few years earlier. The Continental Congress recognized that France resented the loss of its North American possessions, wanted to weaken its rival, and believed that an American victory would ease the British threat to French possessions in the Caribbean. The Continental Congress also hoped that the prospect of commercial gain might motivate Paris. If Britain no longer controlled American ports, France would gain new trading opportunities.

The Continental Congress was so eager for French help that it appointed Silas Deane of Connecticut as a secret envoy to Paris four months before it declared independence. The son of a blacksmith, Deane arrived in France purporting to buy goods that the colonists could sell to Native American tribes. His true mission was to secure military supplies and test the interest of King Louis XVI and his advisors in an alliance with the colonies.

Some Help, But Not Enough

Deane had some initial success. The French agreed to secretly sell gunpowder and ammunition to the Americans. The weapons reached the colonies through the Dutch West Indies and helped sustain the early American war effort. France also agreed to help finance the war, and it allowed American ships that were preying on British merchant vessels to operate out of French ports in the Caribbean. France was unwilling, however, to move beyond clandestine support and openly side with the colonists. Doing so meant war with Britain. That risk seemed too great given the colonists’ slim chance of winning.

Rather than giving up on France, the Continental Congress doubled down on its diplomatic efforts. In late 1776, it sent Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee to join Deane in Paris in the hope that, working with Deane, they could convince France to recognize American independence and openly join the war.

Charm Is Nice, Battlefield Victories Are Better

The seventy-year-old Franklin soon became a celebrity in Paris. He was already well known for his writings and scientific experiments. What he added in person was his frontier charm and disarming wit, which he used to cultivate ties with leading French thinkers and to appeal to their Enlightenment ideals of liberty and self-determination. Public support for the American cause surged. But France still refused to join the war.

What changed French policy was American success on the battlefield. In the summer of 1777, Britain sent a large army south from Canada toward the Hudson River Valley in a bid to split New England, which had been a hotbed for the revolution, from the rest of the colonies. In mid-September, a smaller and less experienced colonial army inflicted heavy losses on British forces and stopped their advance near Saratoga, New York. After the Americans won a second battle in early October, the trapped British forces surrendered.

The Americans’ victory at the Battle of Saratoga dealt a major setback to Britain’s war effort and scrambled political calculations in Paris. King Louis XVI and his advisors now worried less about joining a doomed war and more about missing the opportunity to weaken Britain and limit the threat it posed to the French West Indies. London might respond to its devastating defeat at Saratoga by offering political concessions to entice the colonies to abandon independence. If France remained on the sidelines, the Americans might find such an offer more appealing than continuing a war they could still lose.

A Franco-American Alliance

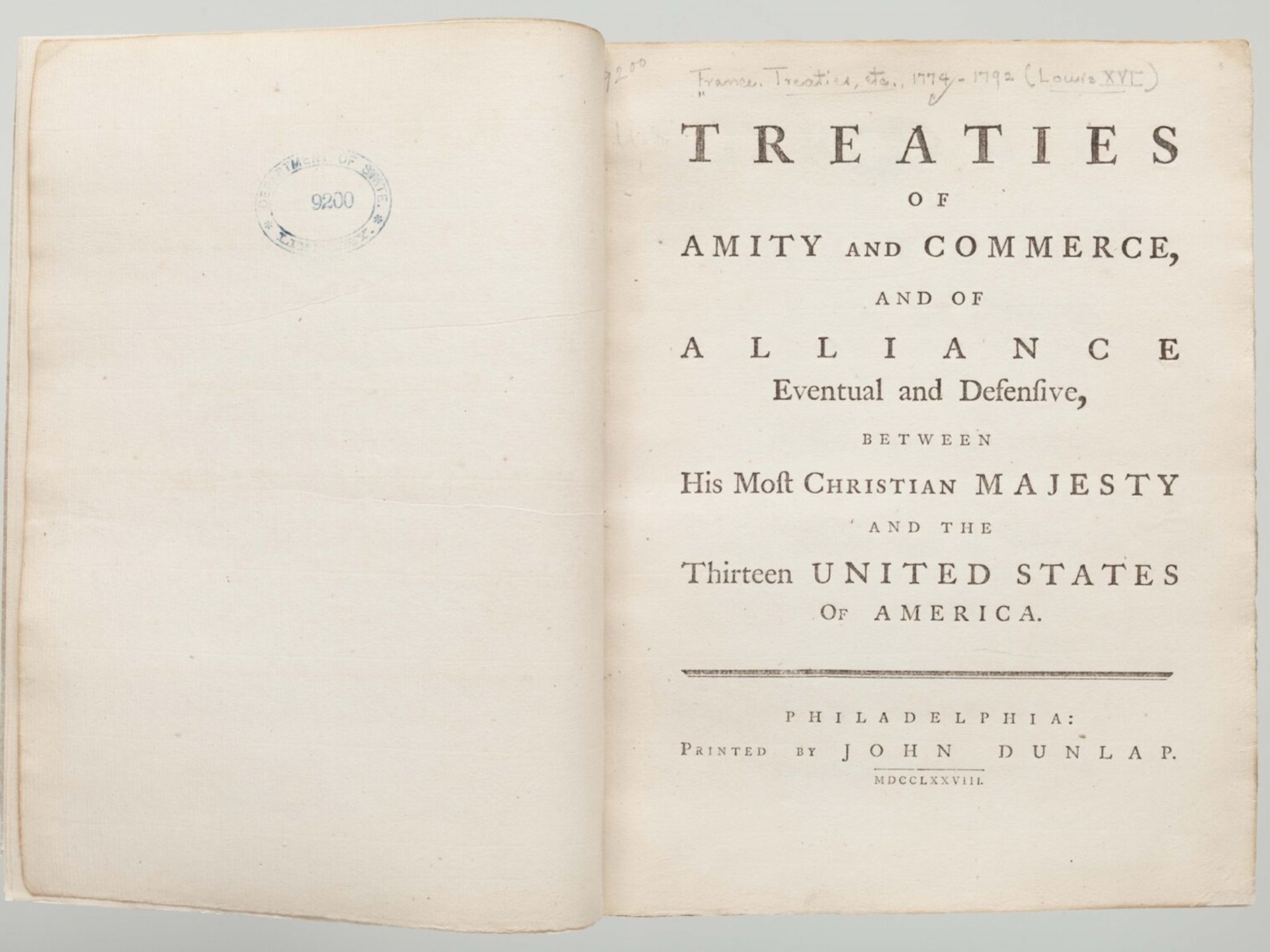

The talks between the American and French negotiators moved quickly. On February 6, 1778, Deane, Franklin, and Lee signed two treaties with France. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce recognized the United States as an independent nation and sought to promote trade between France and the United States. The Treaty of Alliance obligated the two countries to make “common cause and aid each other” in the event that Great Britain expanded its war on the thirteen colonies to France. The treaty also stipulated that neither country would make peace with Great Britain “until the Independence of the United States shall have been formally or tacitly assured by the Treaty or Treaties that shall terminate the War.“

France informed Britain on March 13, 1778, that it had recognized the United States as an independent country. Four days later, Britain declared war on France. The texts of the two treaties reached the Continental Congress on May 2, 1778. The Continental Congress ratified both treaties two days later.

Success Together

France’s entry into the war turned what had been a colonial rebellion into a global struggle. Spain and the Dutch Republic entered the war on France’s side. That forced Britain to divert troops and naval forces from the colonies to the Caribbean and Europe. That relieved pressure on American forces, helping turn the tide on the battlefield in their favor.

The crowning moment came in October 1781 at the Battle of Yorktown. French troops worked closely with General George Washington’s Continental Army to surround a British army led by General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, which backs onto the Chesapeake Bay. Meanwhile, a French naval squadron prevented the British forces from being resupplied by sea. After a twenty-two-day siege, Cornwallis surrendered. It was the last major battle of the American Revolution. Two years later, Britain signed the Treaty of Paris, formally recognizing U.S. independence.

The pivotal role that the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France played in the success of the American Revolution is why a survey I conducted of members of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations ranked it the third best decision in the history of U.S. foreign policy.

Oscar Berry assisted in the preparation of this post.