More on:

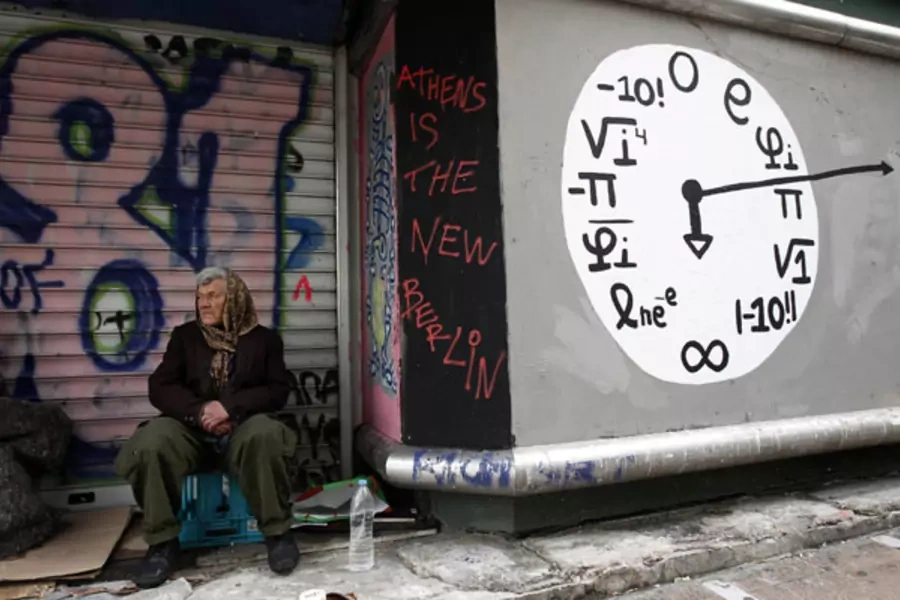

Another cliff in the never-ending Greek drama, as European leaders set a Sunday deadline for a deal. It’s easy to be cynical, but Europe could look very different next week. I now think that “Grexit” is very likely, and it could happen soon.

Later today or tomorrow, the Greek government will unveil its financing and policy proposals, launching what is expected to be an intense set of negotiations over the next several days.

In a telling move, it was announced that all twenty-eight European Union leaders plan to meet on Sunday to discuss contingency plans for a Greek exit from the euro, but not the European Union. If there is an agreement in principal by then, the meeting can be cancelled (and presumably replaced by a meeting of the nineteen euro area members to approve a Greek deal). Statements from the European Central Bank also signaled that if there were no deal by Sunday, it would be forced to end its emergency assistance to the Greek banking system, which would precipitate the immediate and full failure of the banks.

In a further setback, a scheduled meeting of finance ministers was cancelled this morning and it was announced that the Greek proposals would be dealt with in a working group. There is a lot of work to do and not much time.

After months of false showdowns, there are a number of reasons to treat Sunday’s deadline more seriously.

- Conditions in Greece are deteriorating rapidly. ATMs are close to running out of euros, which will cause severe problems for pensioners and others dependent on the banking system and cash. Further, the lack of finance and imports is increasingly disruptive to private activity—supply chains are breaking down, critical inputs running short.

- These conditions will put immense pressure on the Greek government to issue IOUs and change laws to put purchasing power in the hands of those most in need. That means a new currency in practice, if not in law. These measures quickly will become hard (but not impossible) to reverse.

- On the creditor side, we should not underestimate the role of rising parliamentary and public opposition to another bailout for Greece (and not solely in Germany). This limits the willingness and ability of leaders to compromise (more than finance ministers, leaders feel this pressure).

- There was a strong expectation among leaders that the Greek government would present a concrete proposal yesterday. When they did not—their informal ideas on a two stage approach with bridge financing for reforms setting the stage for a bigger deal later represents a step backwards in some respects—a perception that Greece does not want a deal became further entrenched.

There were some small bits of good news from yesterday’s meetings. The cross-party statement of support Prime Minister Tsipras received over the weekend and the statement by the new finance minister yesterday called only for initiation of a meaningful discussion on the necessary restructuring of the debt. That was a softening of their earlier demand for a hard commitment to debt relief, and seems more feasible. Further, though a reported French-led effort to generate some concessions to Greece through a two-stage approach flopped, there does seem to be momentum (backed by EU bureaucratic machinery) for continued, serious negotiations in coming days.

Sunday is not a final deadline. There are creative ways to find bridge financing (including addressing a large July 20 payment due to the ECB) so that even without a deal, it will still be possible to pull Greece back from the brink in coming weeks. The primary impediment to a deal at this stage is policy, not financing. A combination of frustrated creditors and growing pressures on the Greek government mean that dramatic policy reforms are needed for Greece to survive within the eurozone, and I sense little room for compromise on the part of creditors. There seems to be a belated understanding that populism and fixed exchange rate regimes make poor bedfellows. The Tsipras government will need to commit to tough reforms, crossing many if not all of their red lines on pensions, taxes, and labor markets. It is time for Greece to decide.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store