Health

Archive

764 results

- Task Force Report

U.S. Economic Security

![]()

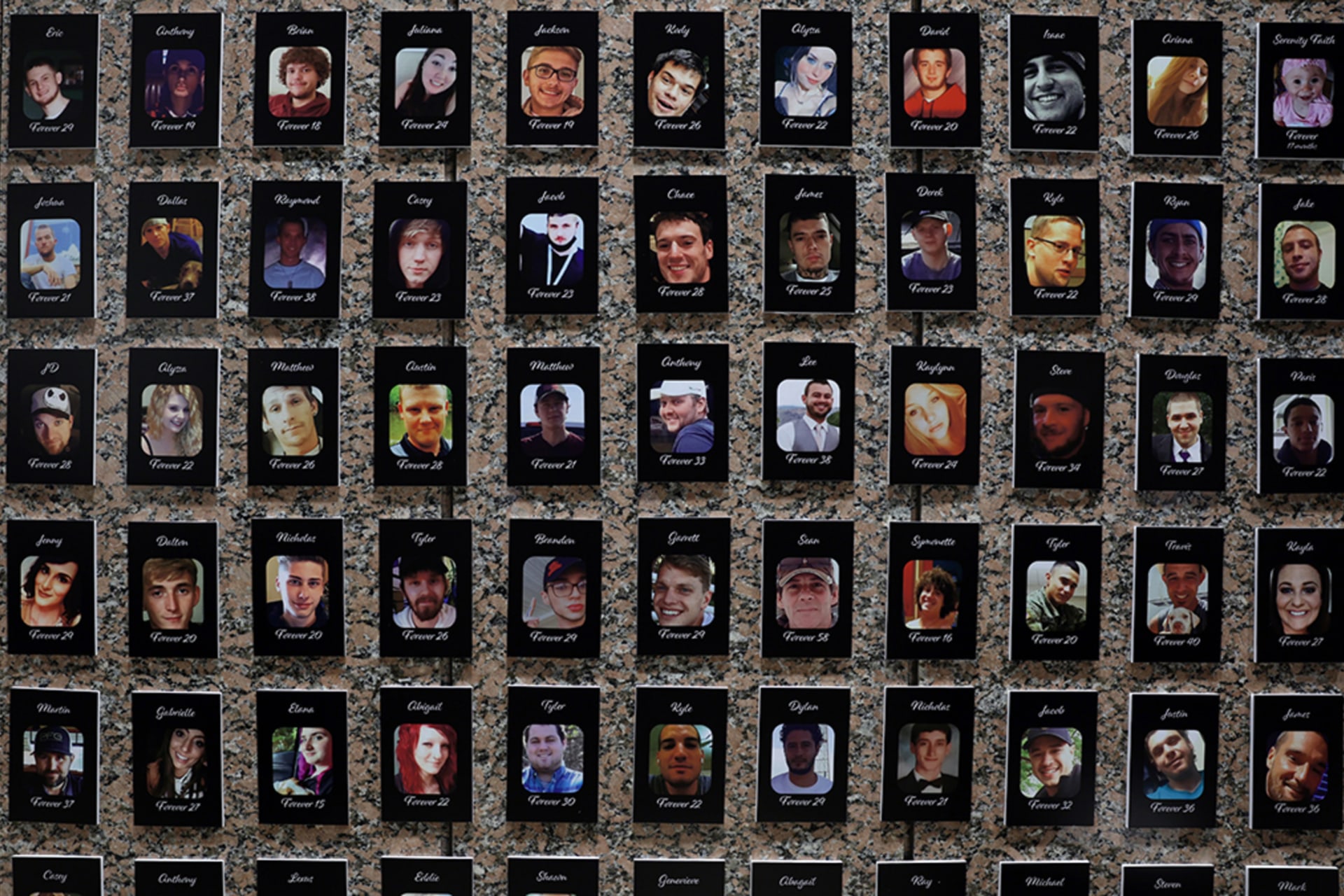

- Backgrounder

Fentanyl and the U.S. Opioid Epidemic

![]()

- Backgrounder

What Does the CDC Do?

![]()

![]() By Thomas J. Bollyky

By Thomas J. Bollyky- Backgrounder

How Vaccines Changed the World

![]()

![]() By Ellora Onion-De

By Ellora Onion-De![]() By Linda Robinson and Noël James

By Linda Robinson and Noël James![]() By Linda Robinson

By Linda Robinson![]() By Linda Robinson

By Linda Robinson![Major Pandemics of the Modern Era cover image]() By Claire Klobucista and Mariel Ferragamo

By Claire Klobucista and Mariel Ferragamo