The Year the Earth Stood Still

The COVID-19 pandemic brought travel around the world to an abrupt halt in 2020. Nations are still trying to grasp the consequences, and restarting movement could take years.

New York City’s Times Square deserted. Dubai International Airport empty. Vatican City vacant. These are some of the scenes of a world no longer in motion.

After the new coronavirus broke out in early 2020, most countries imposed measures such as closing their borders, banning foreign travelers, or ordering their citizens to stay home. These restrictions disrupted international trade and supply chains, but more jarring were the impacts on the movement of people. Countries that depend on tourism are facing economic collapse. Refugees are stranded in crowded camps. Migrant workers have lost their jobs and returned home. Diplomacy between world leaders is largely taking place via videoconference, if at all.

Experts say it will be hard to get moving again while the pandemic is still raging. And the 2020 standstill could permanently change how we interact with one another.

Tourists Stay Home, Businesses Suffer

Thailand is normally flooded with foreign tourists at its street markets, beaches, and resorts. In 2019, travel and tourism comprised nearly 20 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). But with officials forced to close borders during the pandemic, Thailand became “completely paralyzed,” says Siradej Donavanik, vice president of the Thai hotel and resort company Dusit International.

Starting in March, Dusit International saw a historic decrease in guests at its more than three hundred Thai and international properties. To cope, the company had to reduce its fixed costs—most of which are staff-related—by 20 percent. Throughout Thailand, unemployment has soared. On top of the COVID-19 fallout, anti-government protests have further rocked the economy.

“It’s almost like a double whammy, where the pandemic almost took away like 80 percent of our business and now these protests are taking what’s left, especially in the capital of Bangkok,” Donavanik says.

It’s not just Thailand. The number of tourists plummeted worldwide as countries locked down. During the first eight months of 2020, 700 million fewer international tourists traveled compared to the same period in 2019, according to the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization (UNWTO).

The decline in tourism has already caused an estimated $730 billion in losses worldwide, eight times the amount of tourism revenues lost during the 2009 financial crisis, and the UNWTO is projecting up to $1.2 trillion in losses by the year’s end. More than 120 million people in the industry—tour guides, cruise ship workers, restaurant servers, and many others—could lose their jobs [PDF].

No country has escaped the crushing economic effects. Around the world, famous landmarks, natural wonders, and historic sites were emptied of visitors, devastating communities that depend on international tourism for income. Small island developing nations, such as Aruba and the Maldives, could be thrown into catastrophic financial crises, while developed countries, such as Italy and Spain, are suffering job losses and business closures.

Beyond profits, tourism also offers cultural benefits. It allows people to learn about other cultures and promotes dialogue among different groups of people, “highlighting our common humanity,” writes UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. But now that gathering with strangers is a high-risk activity, cultural exchange has plummeted. Around 90 percent of the world’s museums temporarily closed, and although many have shared their collections online, some are unlikely to reopen. Dozens of World Heritage sites that rely on tourist spending to cover maintenance costs shut down, including the Taj Mahal in India, Machu Picchu in Peru, and Victoria Falls in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Performers and artisans, including those in indigenous communities, have also been hit hard.

Borders Close, Futures Put on Hold

In early September, fires ripped through Greece’s Moria refugee camp, leaving roughly twelve thousand people homeless, including eighteen-year-old Afghan refugee Yaser Akbari, his parents, and his three younger siblings. The incident laid bare the myriad challenges refugees face in finding safe settlement.

Akbari says he felt conflicted as he watched Moria, his home of roughly a year, go up in flames. Its residents had been under tighter coronavirus restrictions than others in Greece, sardined in an unsanitary settlement that Akbari says was initially “a shock.” In his new camp, conditions are even worse. “Because the hygiene is terrible,” he says, “[refugees] just wash themselves in the sea.

Experts say such camps are powder kegs for infectious diseases such as COVID-19. Confirmed cases of the coronavirus among refugees have swelled in recent months, though they remain low globally. For now, Akbari and his family are at a standstill as they wait to hear whether Germany will accept them. Still, he says, “I haven’t been hopeless during these times.”

Roughly 79.5 million people have been forcibly displaced globally, an unprecedented number driven by prepandemic traumas such as war, climate change, and state failure. In a cruel twist, those already fleeing for their lives have been caught up in a new, practically inescapable threat: a global pandemic. The recent surge in refugees—displaced people who have crossed an international border and met certain criteria—has overwhelmed authorities’ abilities to care for them and even spurred resentment in wealthy nations. Now, experts say fear that refugees will spread the coronavirus has provided a pretext for countries to shut them out.

In April, Malaysia’s military cited the pandemic to justify turning away roughly two hundred Rohingya refugees. The same month, Italy and Malta closed their ports to boats carrying migrants and asylum seekers due to concerns about coronavirus infections. Other countries have slashed refugee resettlement numbers, and the International Organization for Migration and UN High Commissioner for Refugees temporarily suspended refugee resettlement travel. Such pandemic-related measures have marooned many displaced people where they are, often in countries with frail health systems vulnerable to a pandemic. The coronavirus’s economic fallout has further dimmed their prospects as donors cut funding to aid groups.

The pandemic has stifled other forms of global migration too, with far-reaching and often deeply felt consequences. Families expecting children by international adoption or surrogacy have had their cases put on hold and been forced to celebrate their babies’ births from afar. Muslim immigrants in France and Italy have been unable to send the bodies of deceased loved ones to their home countries. And many of the world’s 164 million migrant workers—from India, Thailand, Ukraine, and elsewhere—have been forced to return home or face deportation after losing their jobs abroad due to the pandemic’s economic ramifications.

Nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment have surged in recent months, and some experts fear countries, including the United States, could use the pandemic as a guise to permanently restrict immigration. The Donald J. Trump administration has effectively halted asylum procedures, suspended many foreign worker visas and green cards, and attempted to block international students from staying in the United States while taking online classes. Still, the United States has joined other countries in exempting migrant agricultural workers and health-care workers from pandemic-related travel restrictions. Some have also expanded protections for migrants and asylum seekers. For instance, Italy and Portugal rolled out measures to grant certain foreigners temporary residency, allowing them to access health care.

Virtual Negotiations, Real-World Consequences

2020 was meant to be a “super year” for international action on the world’s oceans, says Paul Holthus, founder and CEO of the nonprofit World Ocean Council. The second UN Ocean Conference was set to take place in Lisbon, Portugal, and the twenty-sixth Conference of the Parties (COP26) climate talks were slated to happen in Glasgow, Scotland. But because of the pandemic, they have been postponed, setting back progress on issues including ocean acidification and warming and the growing need for climate adaptation. “There was a lot of momentum started the past couple years on adaptation that’s now moving along at a much lower level,” Holthus says.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and advocacy groups including the World Ocean Council, which normally rely on such conferences to push for coordinated action, are trying to champion their causes online. But Holthus says it’s not the same. “For better or worse, these physical gatherings really do galvanize governments, institutions, foundations, and others to make big commitments,” he says, such as targets to achieve carbon neutrality.

The Lisbon and Glasgow conferences were just a few of the many major international meetings postponed, moved online, or canceled. In a first in the history of the United Nations, the UN General Assembly was largely virtual. Though there have been instances of in-person diplomacy—Bahrain, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates all signed deals to normalize ties with Israel following U.S.-led negotiations—they’ve been rare. UN Secretary-General Guterres has called out countries for their failure to cooperate amid the pandemic, as some peace negotiations have stalled and conflicts worsened.

COVID has thrown into reverse a lot of the integrationist aspects of the world that were already sort of on the defensive in recent years, with a tendency towards nationalization.

Pandemic disruptions were sharply felt by groups who provide on-the-ground assistance. Some NGOs evacuated their staff over concerns about the virus’s spread and that employees would be stranded due to travel bans. Even as countries attempted reopening, aid organizations faced challenges returning workers to their posts and delivering food assistance and medical supplies, oftentimes in places where they were needed most.

For the first time since its founding in 1961, the U.S. Peace Corps halted all operations, pulling more than seven thousand volunteers from about sixty countries in mid-March. Near the close of 2020, the government agency’s work remained suspended, leaving thousands of young Americans viewed as cultural ambassadors in limbo and underscoring the damage the pandemic has done to levers of soft power around the globe.

Religious trips were called off or severely restricted: Saudi Arabia suspended umrah, a pilgrimage Muslims can undertake any time of the year, for six months. Israel’s Birthright program for the Jewish diaspora was paused. University study-abroad programs were likewise put on hold, preventing potentially millions of students from often transformative cross-cultural experiences.

The loss of cultural exchange extended to the sports world. The 2020 Olympics in Tokyo were pushed to the following summer, dashing the hopes of elite athletes who spend years training for the games, and organizers now say they will pare back the 2021 events. The Boston Marathon was canceled for the first time in its 124-year history, while other marathons were postponed or restricted to small groups of elite runners. Some major sports leagues resumed their seasons after monthslong hiatuses, but without spectators, such as England’s Premier League and the U.S. National Basketball Association.

What to Expect in the Year Ahead

Restarting global movement won’t be easy as long as the pandemic is around. Governments that have promoted border closures as an essential strategy to protect their citizens from the virus will likely face pushback if they eliminate those closures in the midst of the pandemic, says CFR Senior Fellow Edward Alden. And although countries have had some success limiting disruptions to cross-border trade, there has been little coordination on how to collectively minimize restrictions on people’s movement. “The less interaction you have, the less people understand each other, the harder it is going to be to work together on common problems around the world,” Alden says.

Global distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine will help usher the world toward normalcy, but it will be a long and bumpy path to get there. Some countries, including the United States and Russia, have refused to join a global initiative aimed at distributing billions of doses by next year, raising fears about vaccine nationalism. However, U.S. President-Elect Joe Biden has signaled a more collaborative approach to the pandemic, vowing to keep the United States in the World Health Organization and unveiling a plan that includes an international board to coordinate the global response.

Some forms of international travel are resuming haltingly, as public health officials worry about new outbreaks. Tourists, for example, are on the move again, though not nearly as many as before. Many are opting to travel domestically. Some countries that have reopened their borders to international visitors require them to test negative for COVID-19 before arrival. Others have tried forming “travel bubbles” with neighboring nations that have low caseloads to allow citizens to travel more freely.

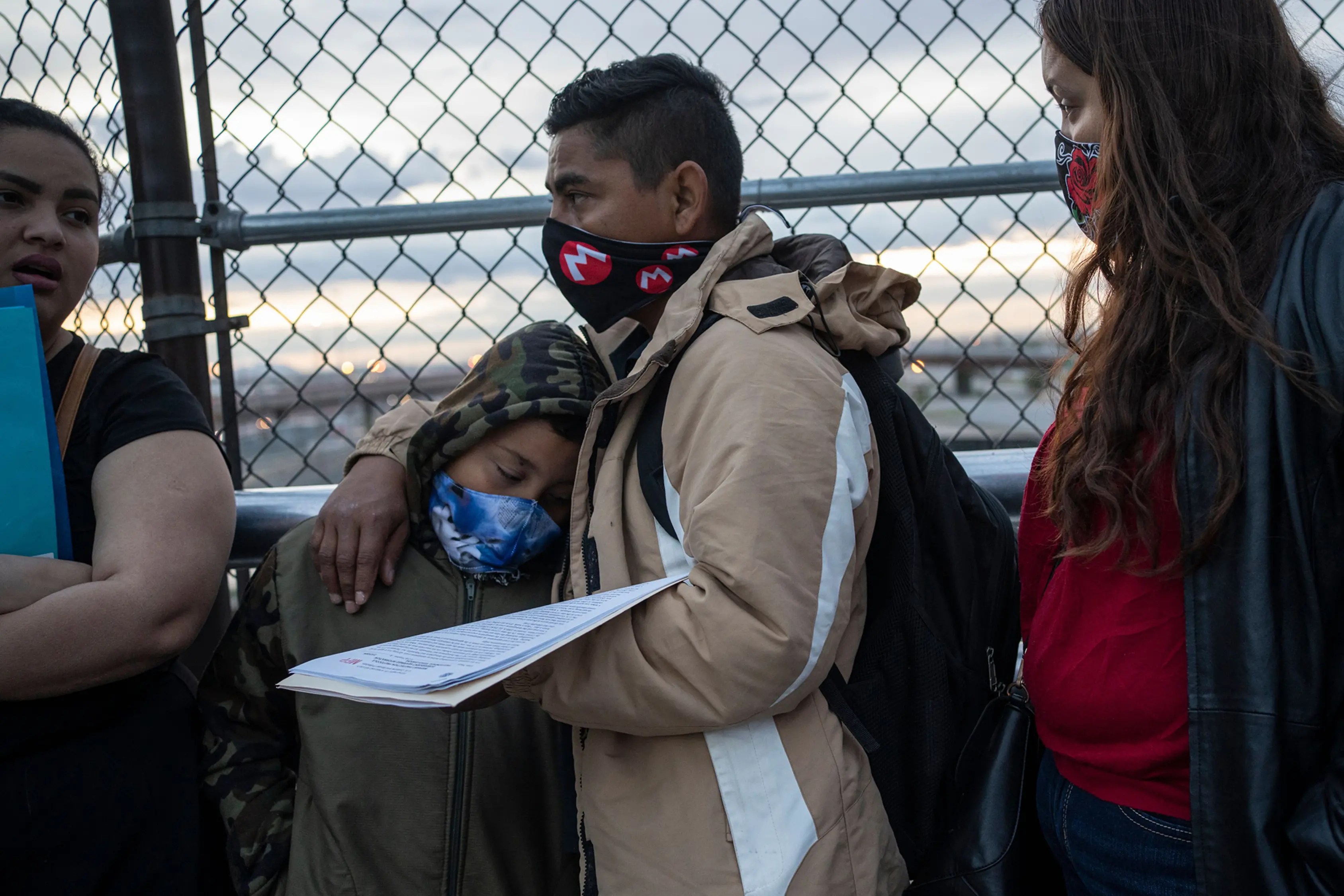

Migration is also taking place, both in spite and because of the pandemic. Sea and land arrivals of migrants in Mediterranean countries plunged in the early months of the pandemic, compared to 2019, but they have since risen again, driven in part by people fleeing the virus’s economic fallout in places such as Tunisia. A similar trend has occurred in apprehensions of migrants along the U.S. southwestern border.

Countries confronting these flows need to take into account humanitarian obligations, public health concerns, and the needs of their recession-throttled economies. Experts say it’s possible for countries to examine asylum claims while imposing measures, such as quarantines and virus testing, to protect public health. Despite the pandemic, Germany and other European countries agreed to take in migrants, including asylum seekers, from Greece after the Moria camp burned down.

Other kinds of global movement may never be the same. Even before the pandemic, Patrick and Holthus say, there was a growing argument to reduce in-person international conferences due to the high costs and environmental consequences. Now, there’s proof that virtual gatherings can work, and so they could stick around for the long term.

In the meantime, experts agree that international coordination is needed to ensure that the world can continue to connect, through this crisis and future ones. “In a very real sense, we are all in this together,” Patrick says.

Additional Resources

CFR’s Edward Alden questions whether an open world can exist after the pandemic.

CFR’s Stewart M. Patrick explores how multilateral institutions failed in the face of COVID-19, and asks whether tourism is an antidote to the global wave of nationalism.

This CFR Backgrounder explains the global effort to create a COVID-19 vaccine.

Think Global Health tracks the coronavirus in countries with and without travel bans during the early days of the pandemic.

This CFR Independent Task Force report looks at how to improve pandemic preparedness.