Controlling the Message in Libya

More on:

In Errol Morris’ Academy Award-winning documentary, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, the former secretary of defense acknowledged a practice common among politicians and government officials: “One of the lessons I learned early on…Answer the question that you wish had been asked of you. And quite frankly, I follow that rule. It’s a very good rule.”

Analyzing the trends of a civil war is difficult whether you are living within the country or thousands of miles away. It is especially challenging when all sides present a biased and inaccurate narrative of events. Libya is no exception and throughout the 114 day, NATO-led intervention, the level of obfuscation and doublespeak used by both sides has been remarkable.

On the one side is the Qaddafi regime in Tripoli, which for decades has been among the most tightly controlled and least free societies for journalists and bloggers. The state controlled all media (reportedly overseen by Qaddafi’s son and now-indicted war criminal, Seif al-Islam), including telecommunications and internet access, and also blocked foreign satellite broadcasts. In fact, prior to the February uprisings neither Al Arabiya nor Al Jazeera had bureaus or local correspondents in Libya. Not surprisingly, of the 196 countries assessed in the Reporters Without Borders 2010 Annual Press Freedom Index, Libya was tied with Eritrea near the very bottom, at 192.

Since mid-February the relationship between government officials backed by state security forces and foreign reporters has only deteriorated. The Qaddafi regime has harassed and detained reporters and photographers for questioning on flimsy pretexts, physically abused many of them, sexually assaulted others, potentially authorized the execution of at least one, and expelled anyone who attempts to leave the Rixos Hotel to do independent reporting. Just last Wednesday, for merely publishing man-on-the-street reports from the suburbs of Tripoli, the regime expelled David Smith of The Guardian and Adrian Bloomfield from The Daily Telegraph.

Moreover, the regime’s strategic communications strategy appears to be one based on the principles of lie, hide, or deride. Particularly absurd are the lengths to which regime media handlers have gone to present “evidence” of civilian casualties caused by NATO airstrikes—of which there are remarkably few credible reported cases. Veteran New York Times correspondent John Burns summarized the regime’s desperate attempts in a piece aptly titled: “In Libya, Delusion Makes a Last Stand.” Burns wrote that for government spokespersons, “there is still only one essential reality, the dictatorship of Colonel Qaddafi, and all other facts must be bent, at whatever cost to credibility, to keeping him in place.”

NATO’s communications strategy, meanwhile, has been defter and McNamaraesque: staying on message regardless of the question asked or the facts on the ground. Then, when presented with uncomfortable information that runs counter to the message, NATO representatives either refuse to acknowledge or downplay the evidence. To take two notable examples.

First, NATO officials maintain that they have “no boots on the ground,” and thus “no way to independently verify” what happens in Libya. This is an implausible claim, since western air forces generally will not provide close air support in contested environments without on-the-ground assistance from trusted forward air controllers. For example, in 1994, Lieutenant General Michael Rose, Commander of the UN Protection Force in Bosnia-Herzegovina, deployed a team of eight British Special Air Services (SAS) officers disguised as UN military observers to the safe haven of Gorazde to provide real-time targeting information. Similarly, in late May, The Guardian revealed that former SAS soldiers “are passing details of the locations and movements of Gaddafi’s forces to [NATO’s] Naples headquarters,” and that “the former soldiers are there with the blessing of Britain, France and other NATO countries, which have supplied them with communications equipment.” When asked about the role of retired allied military personnel in Libya, a NATO spokesperson admitted that “NATO is quite astute. It will take information from any source it can…I also saw that piece on the television and I am not going to speculate who those people are.”

Second, NATO claims that it is enforcing the UN Security Council Resolution 1970 arms embargo for Libya, which prevented “the direct or indirect supply…of arms and related materiel of all types, including weapons and ammunition, military vehicles and equipment, paramilitary equipment, and spare parts for the aforementioned, and technical assistance, training, financial or other assistance.” As I’ve noted earlier, NATO has enforced the arms embargo rarely and selectively. This includes one particular public relations gaffe, in which NATO released a video of a Canadian ship boarding a rebel tugboat, finding small arms, 105MM howitzer rounds, and “lots of explosives,” and then, after contacting NATO Headquarters, allowing the arms-laden tugboat to pass through to Misurata.

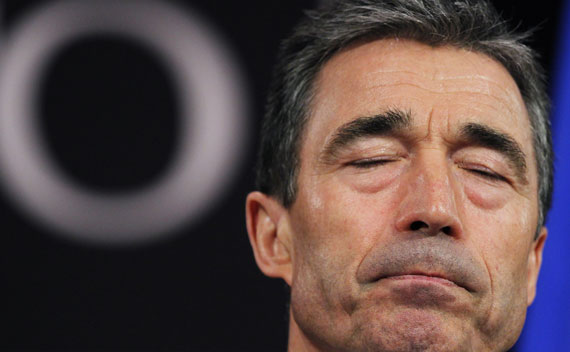

On June 29, Le Figaro revealed that France had “begun parachuting rocket launchers, assault rifles, machine guns and anti-tank grenades to rebel forces on the ground.” French Foreign Minister, Alain Juppe, soon acknowledged the report adding, “We informed our partners in NATO and the Security Council about these deliveries." When NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen was asked about France’s blatant violation of the resolution, he responded blithely: “I don’t consider the so-called arms drop a problem. But again, I would like to stress that it’s not part of the NATO operation, and that’s all I can say about it.”

Of course, reliable data is challenging to obtain through the fog of war. But the doublespeak coming from both sides of the fight is Libya is remarkable in its divergence from publicly available information gleaned from less biased sources. What sources do you rely on in trying to understand what’s happening on the ground in Libya?

More on:

Online Store

Online Store