How India Could Actually Reach Its Audacious Solar Targets

PARIS—Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has set a dramatic target for solar power: 100 Gigawatts (GW) by 2022, or more than half of all solar installed to date globally by the end of 2014. Back in March, I questioned whether these targets were realistic, given that India currently has less than 5 GW installed today. But after digging into India’s progress to date, asking Modi administration officials about the sincerity of their target, and understanding the calculus of Indian and foreign solar developers who are pledging billions of dollars of solar investment, I am turning into a believer. India’s target, still aspirational, could actually materialize.

Today I, along with Gireesh Shrimali and Dan Reicher of the Stanford Steyer-Taylor Center on Energy Policy and Finance, released a report arguing that India’s solar ambitions are both reachable and central to the climate commitments that India volunteered ahead of the ongoing Paris Climate Change Conference. You can read the Wall Street Journal’s coverage of our report here, and you can read the full report here. In a nutshell, our study reaches three conclusions:

More on:

First, for solar power to succeed as a serious climate tool in India, it will also need to deliver an array of domestic co-benefits—from improving power reliability and access to electricity to cutting air pollution and energy imports—thereby building significant political support and investment to dramatically ramp up solar deployment.

Second, three very different segments of the solar industry—utility-scale, distributed, and off-grid solar—will be required to deliver both climate results and domestic co-benefits to India.

Third, the Indian national and state governments, with the support of countries and institutions around the world, can advance the development of these diverse segments of solar by pursuing four building blocks of a successful solar strategy: reform the utility sector; harmonize federal and state policies; secure substantial and cost-effective financing; and foster the diffusion of technology and standards from abroad. With these building blocks in place, India can greatly accelerate the deployment of solar power and with it progress toward the world’s climate imperative.

In this post, I want to share some of the insights from my recent trip to India, a whirlwind tour from the deep southern states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu to the capital city New Delhi in the north. Here are four on-the-ground insights about the challenges and opportunities facing India as it ramps up its deployment of solar:

1. There is a tension between foreign optimism and domestic cynicism. Every time I spoke with a foreign solar developer or investor, I heard a similar, soaring story of unbounded opportunity. If coal, the dominant power source for India today, were the only option to sustain present economic growth of 7–8 percent annually, India would have to build around 15-25 GW of new coal plants every year. But India has no chance at building that much coal every year, because of obstacles to increasing coal supply and the low investor appetite to build new coal plants, given that existing plants are increasingly unprofitable. That means the opportunity for solar is enormous to meet India’s insatiable appetite for power as its economy grows. Importantly, because the “capacity factor” of solar is about 20 percent (i.e., solar actually only generates about a fifth of the energy that it would generate if the sun were always directly overhead), 15–25 GW of demand for coal converts to somewhere between 40–75 GW of demand for solar every year. Just tapping a small fraction of that new demand every year will enable India to quickly reach its 100 GW goal and more.

More on:

But not everyone was boundlessly optimistic, and in general I found that domestic solar developers used their previous experience doing business in India to temper wild expectations of growth. Interestingly, many domestic solar developers are actually successful businesses in other sectors that have pivoted into solar energy, recognizing the business opportunity. But their experience elsewhere—from textiles to thermal power—is that infrastructure transformations move slowly in India. Finding large tracts of land, securing permits, and driving down the high cost of domestic debt are some of the myriad barriers that solar developers face. Extrapolating from the high rate of stalled infrastructure projects in India, these developers infer that solar adoption will increase steadily but slowly.

The answers to two questions separate the optimists from the pessimists. First, will the solar transformation resemble the rapid build-out of telecom infrastructure like cell towers, or will it resemble most other infrastructure programs that are halting and troubled? And second, will the Indian economy’s 7–8 percent economic growth pull solar power into the market to fuel rising demand, or will the difficulties of building out new power infrastructure hold India’s economy back? These are questions that the policymakers in the Modi administration are grappling with as they try to remove obstacles from solar’s path that have tripped up other infrastructure projects. But after meeting with several officials, I am struck by their sincere conviction that the 100 GW solar target is achievable.

2. Recent bids for utility-scale solar are unsustainable, but solar in general is already very competitive with coal. Everybody was talking about SunEdison’s astonishingly low recent bid: the company promised to charge fewer than 7 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) to sell power to the state of Andhra Pradesh from a 500 MW solar project. Most developers and engineering companies I talked to scratched their heads wondering how this low price could possibly result in SunEdison making money off the project. And many Indian energy analysts used this data point, along with SunEdison’s recent woes, to infer that solar is not actually competitive. Rather, they contend, at present solar is only artificially competitive because companies are bidding numbers that they cannot possibly deliver (at least profitably).

But 7 cents/kWh need not be the figure of merit to justify solar’s competitiveness. Indeed, 9 cents/kWh is the rough cost of power from new coal power plants, which is what solar power must compete with. This is a crucial insight—existing coal power plants that are already fully depreciated can afford to sell power at prices below 6 cents/kWh. But remembering that solar developers aim to serve the new power demand to fuel India’s economic growth, solar power’s relevant competitor is power from new coal power plants. Whether or not the SunEdison bid is sustainable or not, most developers and public officials I talked to agreed that 8 cents/kWh is a sustainable price for solar power plants to charge, and at that level, solar is still very attractive as a new source of power.

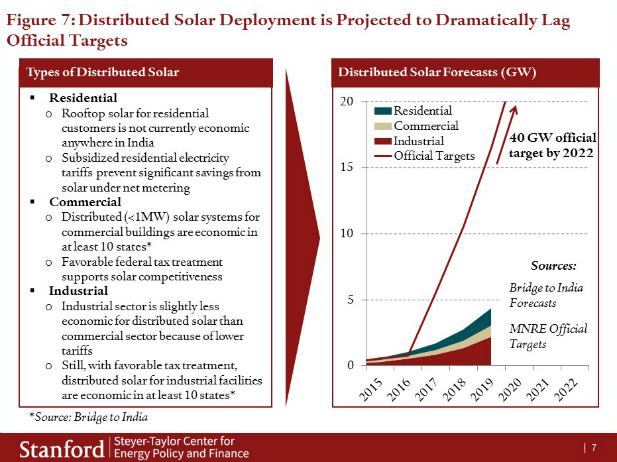

3. After a slow start, distributed/rooftop solar deployment could soon take off. As is evident in the figure below from our report, the deployment of smaller-scale solar (i.e., less than kW-scale projects, often on rooftops, that are tied into the urban distribution grid) has increased much slower than that of utility-scale (> 1MW) solar. In fact, of the 4.5 GW of solar currently installed, roughly 4 GW is utility-scale solar, even though distributed solar is supposed to account for 40 GW of the total 100 GW Modi administration target.

Nevertheless, in my conversations with state government officials and utility regulators, I gathered that distributed solar is gaining momentum. State regulators in India are grappling with some of the same problems as we have been dealing with at the state level in the United States—for example, should states allow “net metering,” in which distributed solar power production can offset purchases from the grid, and at what rate should utilities compensate solar power for their exports to the grid? A majority of Indian states have now adopted net metering policies, and the trend is toward policies that make it worthwhile to install distributed solar.

Still, more policy support is necessary to drive financing toward the distributed solar sector, especially to support third party financing models, which have driven rapid distributed solar adoption in the United States. One area for improvement is to ensure that federal tax credits (e.g., accelerated depreciation) apply to third parties who finance distributed solar. Another policy suggestion—which I heard from Tobias Engelmeier from the Bridge to India consultancy—is to make it easier for a third party who owns a distributed solar asset to sell the power to a customer other than the one on top of whose roof the solar panels sit. This could reduce default risks faced by third party financiers if the customer who owns the roof cannot pay for the power. It also foreshadows a business model in which a third party developer builds a microgrid in an industrial area, connecting up several rooftop solar systems to offer a robust, self-sufficient alternative to the grid to businesses in the area.

4. Business model innovation is the most important opportunity for off-grid solar. I entered India under the assumption that off-grid solar was an economics play against kerosene. If a developer can provide energy—through a solar home system or a small “microgrid” powered by solar panels and batteries—that is cheaper than the energy from kerosene used for lighting and heat, then off-grid solar should naturally succeed. Unfortunately, because the government heavily subsidizes kerosene, the per-kWh cost of kerosene energy is often lower than the per-kWh cost of off-grid solar systems. Therefore, I assumed, off-grid solar just could not take off until politicians solved the heretofore intractable problem of subsidy reform.

In fact, I found out that the economic comparison of per kWh costs between kerosene and off-grid solar has very little to do with whether off-grid solar can succeed. Rather, off-grid solar will succeed if it provides energy services that customers value—not kilowatt-hours of electricity that customers find inexpensive. Thus, if an off-grid developer (like Selco, whose founder Harish Hande was kind enough to explain all of this to me) offers an electric sewing machine to boost economic output, or a television set that the whole community uses to watch cricket, then rural customers will be very willing to reliably pay for off-grid solar every month. Currently, off-grid solar systems that only power lights, fans, and cell-phones face serious collection issues, because rural customers can miss a payment and tolerate service interruptions. But when innovative companies provide services that anchor the livelihoods and entertainment of customers currently off the grid, they will access a vast, untapped market and improve access to energy.

Each of these four insights entails opportunities for solar but also immediate barriers that India will have to surmount. My final day in Delhi, the air pollution was so bad that the government announced an emergency scheme to take half the cars off the road. Solar, if deployed as a diverse mix of centralized and decentralized installations, can help alleviate air pollution and achieve several other domestic co-benefits at the same time. For this reason, Prime Minister Modi has referred to solar as India’s “ultimate energy solution.” But can his administration execute a wide-ranging strategy to realize this potential? After asking a lot of hard questions, I’m now willing to bet that the answer is yes.

Online Store

Online Store