Could Cheap Natural Gas Undermine a Carbon Price?

More on:

Cheap natural gas has split the climate debate into two camps. One celebrates the development, emphasizing that natural gas cuts emissions when it replaces coal, and arguing that abundant gas reduces emissions as a result. The other bemoans the news, noting that inexpensive natural gas makes it tougher for zero-carbon energy to compete and arguing that this will ultimately result in higher, not lower, emissions.

Which view is right? Exploring a set of simulations just released as part of the Annual Energy Outlook published by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) provides some neat insight. For the first time, the EIA simulates not only the impact of low natural gas prices and the impact of carbon pricing but also what happens when you combine the two. The results are really interesting.

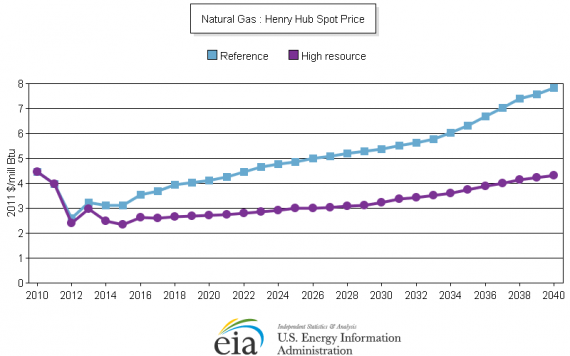

The plot below shows the two natural gas price assumptions that the EIA looks at. (I made all the plots using the EIA’s awesome AEO Table Browser.) The high natural gas price scenario is based on what analysts currently believe the natural gas resource looks like. The low price scenario results from assuming that each gas (and oil) well yields twice as much fuel as currently believed; well spacing declines so that more wells can be packed into a given area; and undiscovered oil and gas resources are 50 percent higher than currently assumed, among other tweaks. Expected prices, you’ll notice, diverge pretty sharply over time.

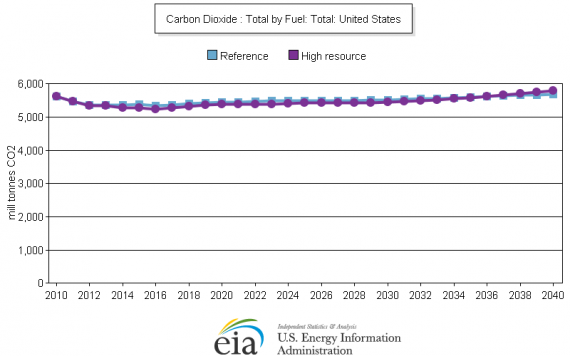

If you assume no price on carbon, you end up with the emissions in the figure below. Super-cheap natural gas cuts emissions (though barely) for the next couple decades. After that it actually begins to make things (barely) worse.

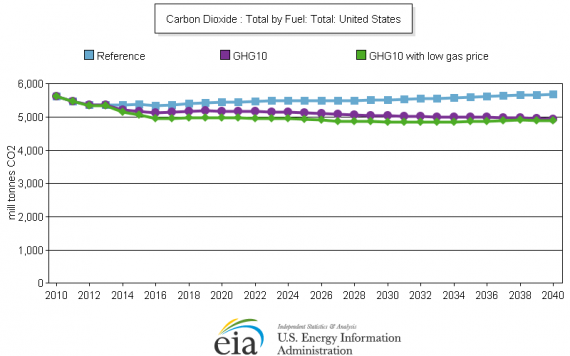

The next figure shows what happens when you put a modest price on carbon. Here the assumed carbon price is ten dollars a ton starting in 2013 and rising 5 percent annually through 2040. Now what you find is that cheap gas consistently helps. The carbon price cuts emissions relative to business as usual – but the carbon price combined with cheap gas does even more.

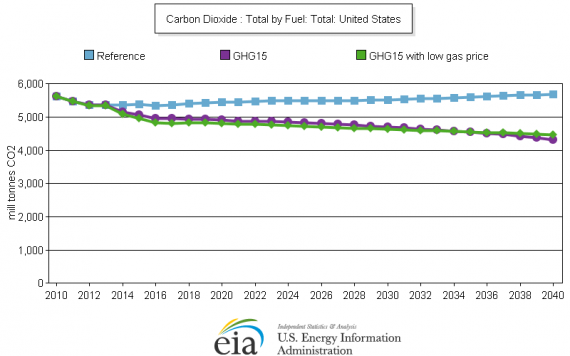

Things get even more interesting, though, when you step the carbon price up a bit. The next figure assumes that a carbon price starts at fifteen dollars in 2013. (The other details remain the same.) Now we’re back to a pattern that’s a bit more like the reference case: Cheap gas helps for the next couple decades before becoming a climate liability later.

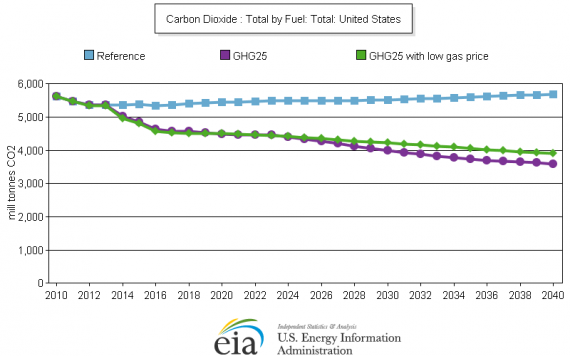

Perhaps the most interesting chart, though, is the final one, displayed below. It shows what happens when you’ve got a carbon price that starts at twenty-five dollars in 2013. Now low natural gas prices help, though almost imperceptibly, for the next decade. After that, though, they actually hurt, and by the time you get out to 2030 and 2040, the penalty imposed by cheap gas becomes pretty large.

There are, as usual, caveats galore here. This is one model, and one set of technology and market assumptions, so its results should be treated with great care. It says nothing about the costs of emissions reductions -- and abundant natural gas can make hitting the same emissions trajectory cost less. Moreover different people will interpret these figures in differing ways. Some will say the results they show that natural gas is bad news (at least in the long run) for climate change. Other will argue that they offer a series of misleading comparisons: in a world with cheap natural gas, it may be more politically feasible to impose a higher carbon price, and if that’s true, cheap gas could still mean considerably lower long-run emissions. A third camp (undoubtedly dominated by economists) might argue that these projections simply show that cheap natural gas might make a rational carbon policy consistent with higher emissions than it otherwise would be.

Who’s right? That’s a tough question. There’s a lot more to be analyzed here, and even more that’s probably not amenable to neat and clean analysis. What’s for certain, though, is that the consequences of natural gas for U.S. emissions are more complex and intriguing than most people have assumed.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store