Critiquing U.S. Aid in Pakistan: A Second Take

More on:

Emerging Voices features contributions from scholars and practitioners highlighting new research, thinking, and approaches to development challenges. This post is from Nadia Naviwala (@NadiaNavi), an Islamabad-based researcher and writer. Here she details a recent New York Times story on U.S. development assistance in Pakistan, and explains why investigating aid efforts there requires a different approach.

The New York Times published a story last month about the second largest United States Agency for International Development (USAID) mission in the world: Pakistan. The Times argued that despite over a decade of work and billions of dollars, “aid has had minimal impact on the ground,” thanks to overreliance on “American contractors with little development experience,” and corrupt Pakistani subcontractors that don’t do the work or return equipment.

As a former country representative for the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), a USAID desk officer, and a Congressional staff member who helped to lead the creation of the Commission on Wartime Contracting, I have been involved in U.S. assistance efforts in Pakistan since 2009.

My research and experience with Pakistani civil society made me an early and vocal critic of foreign-led development efforts in Pakistan. Yet the Times story’s criticisms are not supported by the evidence.

A Lawyer in Peshawar Sues USAID

The Times story centered on a USAID contract in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) terminated in 2010 for waste, fraud, and abuse. As the Times told it, three lawyers in Peshawar accuse USAID of failing to recover U.S. taxpayer money from a court settlement that awarded the agency damages.

It continues:

“A recent lawsuit against the agency highlighted the challenges and image problem it faces in a country where American aid is often viewed with suspicion…“Documents and correspondence filed by the lawyers lay bare the money and equipment that went to waste in a project in Pakistan’s insurgency-hit tribal areas….

“U.S.A.I.D. suspended Academy for Educational Development from United States government contracts…Academy for Educational Development was also awarded at least $300,000 after a drawn-out arbitration process with its Pakistani subcontractors — money that should have been returned to U.S.A.I.D. The Pakistani lawyers who filed the suit said that the aid agency had made no attempt to recover the money.

“For many Pakistanis, the case is another puzzling instance of wastefulness. ‘This is U.S. taxpayer money,’ Sanaullah Khan, one of the lawyers, said. ‘Why is U.S.A.I.D. walking away from an ongoing legal process?’”

The unasked question is, why did a Pakistani lawyer in Peshawar dedicate his time (unpaid) to chase American taxpayer money? After contacting Sanaullah Khan, one of the lawyers involved in the suit, it became clear that the Times is conflating two sets of cases. The first relates to local court battles over contracting corruption, for work USAID supported in Pakistan before 2010. The more recent lawsuit is over unpaid legal fees that have nothing to do with the development agency’s impact there.

In 2010, USAID discovered corruption tied to the Academy for Educational Development (AED), a U.S. contractor working in FATA, thanks to a whistleblower who wrote a letter to President Obama.

Khan, AED’s Director of Legal Affairs at the time, says he was left behind to fight off subcontractors after USAID cut ties and AED dissolved. Engineering subcontractors then sued AED for around $9 million, though a Peshawar court in 2013 decided these claims were illegitimate. They awarded damages in the other direction—subcontractors were to pay AED a total of $300,000, while AED owed them only $60,000.

As to why USAID is not getting involved in the legal process to claim this $300,000 (which is still tied up in appeals), the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad explains:

“AED’s subcontractors are not and were never in a contractual relationship with USAID. Because USAID’s contract was with AED and not with AED’s subcontractors, there is and was no legal way for USAID to recover funds.”

In addition, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) reached a settlement with AED in 2011. According to the terms, AED paid USAID $5.3 million dollars, plus another $350,000, plus the company’s remaining cash assets—possibly totaling over $15 million. It released both parties from future claims.

Khan is now suing the dissolved AED in a Peshawar court for $750,000 in unpaid legal fees (the second case). Khan named USAID’s Pakistan mission director in the claim and asked the court to freeze USAID’s bank accounts in the country until he is repaid. His case faces a challenge by the 2011 DOJ settlement that specifically states the U.S. government is not liable for AED’s lawyers’ fees.

In the Court of Public Opinion

Khan likely hoped the Times publicity would help advance his cause. Less clear is why the Times extrapolates these cases to make their own about USAID’s minimal impact in Pakistan when the details undermine their argument.

The fraud the Times describes happened over five years ago—before the implementation of the $7.5 billion, five-year aid program (known as the Kerry-Lugar-Berman Act) that the story calls into question. Further, the Obama administration acted swiftly and severely against AED’s corruption, effectively “killing” the company. They touted AED’s investigation and suspension as a success story in USAID accountability.

The Times’ editors likely realized the overreach and within days of publication changed the title from, “In Pakistan, U.S. Aid Agency Produces Dubious Results,” to “In Pakistan, U.S. Aid Agency Faces Skepticism.” (They also added a lengthy editor’s note about their interactions with USAID in reporting the story.)

Surprisingly Khan is not among the skeptics of U.S. development programs. He supports the work AED and USAID did in FATA. “Only the engineering team was involved in corruption. The rest of the program was good and useful. I’d say ninety percent of all other components—in agriculture, health, education, training, development, there are many—worked tremendously well.”

Contracting with Governments

The Times’ criticism—and its focus on U.S. contractor relationships as a source of the problem—detracts from more useful scrutiny of USAID’s work in Pakistan over the past five years.

In 2009, around the time of the AED scandal and the new multi-billion dollar aid package, USAID reorganized the way it implements projects in Pakistan. The agency terminated contracts with U.S.-based companies (at the behest of the late Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, then U.S. envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan) and started shifting funding to local partners, primarily the Pakistani government.

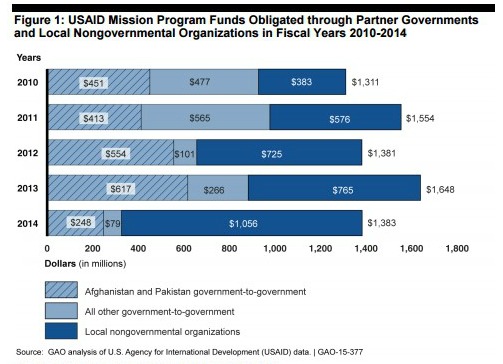

The Pakistan package has since been one of the largest experiments in contracting with a foreign government—referred to as government-to-government or “G2G” assistance—in the world. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), between 2010 and 2014, the value of G2G contracts in Afghanistan and Pakistan exceeded the total value of contracts with all other foreign governments (see: Figure 1).

The approach is not without flaws. G2G would be more aptly named B2B, or bureaucracy-to-bureaucracy. The slow pace has been a huge frustration to both Pakistani and U.S. officials and prompted the gradual reintroduction of U.S. contractors in complex arrangements with government institutions— a relationship worth investigating.

The Times makes an important point that whether U.S. money is lost to graft and waste matters, but fails to substantiate it. A more valuable question is whether U.S.-funded projects in Pakistan, including schools, clinics, roads, and power and water infrastructure, are operating and can be sustained once handed over to local governments. And whether the hundreds of millions the U.S. invested in training, capacity-building, policy, and advocacy programs are helping to meet that goal.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store