Getting Qaddafi to The Hague: The Case for ICC Prosecution

More on:

With the collapse of Muammar al-Qaddafi’s regime in Libya, attention has naturally turned to bringing the former strongman to justice.

But where?

In late June, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant, citing the dictator’s crimes against humanity. Self-styled foreign policy “realists” responded with angst, predicting the specter of prosecution would only prolong the conflict, by eliminating the possibility of a negotiated settlement. The Internationalist rejected this alleged peace-justice trade-off, predicting the warrant would only hasten the collapse of his political support. (Future historians will have to sift through the record to see who was right).

The hot debate now is whether the ICC is the proper venue for holding Qaddafi to account—or whether a national, Libyan-owned judicial proceeding should take precedence. Here’s one vote for transferring Qaddafi to The Hague as soon as he’s apprehended.

Whether domestic or international tribunals are better at delivering justice and accountability for atrocities remains a bone of contention. Over the past two decades, the international community has experimented with different models. These include international tribunals, including the ICC and, beforehand, the ad hoc International Criminal tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda (ICTR); various domestic tribunals, such as Argentina’s for crimes committed during the “dirty war”; and a variety of “hybrid” institutions, such as the Special Court for Sierra Leone (which relied on judges from Uganda, Northern Ireland, and Samoa but occurred in the country) and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal for Cambodia (which had a mixture of national and international judges).

There is much to be said for relying on domestic courts to address crimes committed in the territory of the state in question. All things being equal, such proceedings are more likely to be perceived as legitimate by the country’s population, while reinforcing the rule of law and helping to bolster national legal institutions and systems. The administration of George W. Bush repeatedly advocated for the national approach on these grounds—a stance reinforced, of course, by its animus toward the ICC.

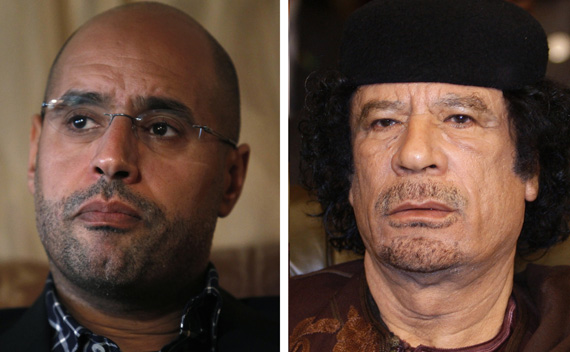

The official U.S. government position appears to be that Qaddafi’s legal fate rests in the hands of Libya’s Transitional National Council (TNC). The U.S. permanent representative to the United Nations, Susan E. Rice, declared on Tuesday, “The Libyan people will have to decide whether to try Muammar al-Qaddafi themselves for crimes against his people, or surrender him to face justice before the ICC.” What the TNC will ultimately decide is unclear. The same goes for Saif al-Islam, Qaddafi’s son and Libya’s former de facto prime minister, who also faces an ICC arrest warrant and remains at large, for now. “Everything is possible, it is up to the TNC to decide,” TNC envoy to Paris Mansour Saif al-Nasr stated on Monday, “It is possible that he [Saif] will be handed over to the ICC but it’s also possible he won’t.”

The problem, of course, is that a country must have a competent judicial system to undertake such trials in an unbiased and professional manner. The Rome Statute of the ICC accepts this logic, by embracing the principle of complementarity. That is, the Court can claim jurisdiction on one of only two conditions: when the country lacks a functioning judicial system, or when state authorities have manifestly failed to carry out a credible investigation into alleged atrocity crimes.

If there were ever a strong case for ICC jurisdiction, it is Libya—a country with no functioning judicial system after four decades of arbitrary, dictatorial rule. Given the monumental governance challenges confronting the TNC, it could take years of international assistance before the Libyan state is capable of conducting a credible trial of Qaddafi and his henchmen. And yet there will be enormous pressure, given the understandable thirst for retribution, for the TNC (or its immediate successor) to fast-track Qaddafi to trial in a judicial proceeding that could become a farce.

Provided that Qaddafi is captured alive—and kept that way—there are several potential scenarios in the coming weeks. The first, most straightforward, and ideal, would simply be for the TNC to transfer Qaddafi and his fellow defendants to The Hague to face the ICC.

A second scenario would be to conduct a trial in Libya first. Earlier today TNC Spokesperson Abdel Hafiz Ghoga suggested that the dictator would have to face trial in Libya before facing the ICC. It is unclear, however, that the ICC judges, having begun a legal proceeding against Qaddafi, would agree to an in-country trial, even if formally petitioned by the new authorities in Tripoli, since it would require Libya to persuade the court of its capacity to conduct such a complicated judicial proceeding.

The third scenario would be for the UN Security Council (UNSC) to weigh in on behalf of the Court. If the latter balks at transferring the Qaddafis, the ICC could inform the Security Council of Libyan non-compliance. The UNSC, however, has been rather weak at being the attack dog of the ICC.

Under a fourth scenario, the UNSC could weigh in not on the side of the Court but the TNC, invoking Article 16 of the Rome Statute, which permits a one-year deferral of any ICC prosecution, to suspend ICC proceedings. This could allow the new Libyan authorities time to put into place new institutions and mount their own trials. The downside of this option, as suggested above, is that one year is an awfully short time horizon for getting this done.

A final scenario would be for the UN Security Council to create a hybrid trial, along the lines of the Special Court for Sierra Leone, which was set up jointly between that country and the United Nations. This option would essentially split the difference: allowing the trial(s) to occur in Libya itself, while providing sufficient external judicial expertise, as well as financial and other resources, to ensure a credible, professional proceeding.

It is unclear, as of this writing, which scenario is most likely. And Qaddafi may yet escape justice by skipping town to Angola or Zimbabwe—neither of which is party to the ICC.

Sometimes it pays to keep it simple. Libya’s new leadership will also have plenty of other problems on its plate. For now, the Libyan rebels can likely accomplish the most by making Saif al-Islam—who infamously shouted, “To Hell with the ICC” on Monday—face that very institution with his dad by his side.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store