Hurricane Sandy: Is There Anything We Can Do About Climate Change Soon?

More on:

The East Coast is slowly returning to normal life after Hurricane Sandy – and pundits, scientists, and journalists are quickly diving into a debate over what the storm says about climate change. I have nothing useful to add on that matter. But I do wanted to shed light on an important related question that has come up: is it even possible to change the course of climate change over the next fifty or so years?

The uninformed conventional wisdom is something like “of course we can change things if we start shifting to clean energy”. As I explain below, that’s not really true. David Roberts does a nice job of laying out what I’d call the “informed conventional wisdom” in a series of tweets (!) that I’ve concatenated here:

“Realtalk: The oceans will continue to rise for at least 50 years no matter what we do. We can only affect the latter half of century. There’s nothing Obama (or Bush, Clinton, Bush, or Reagan) could have done to prevent Sandy. Climate don’t work that way. Big time lags. The mega-hurricanes that we CAN prevent are the ones that will bedevil our children in the latter third of this century. The best we can do for ourselves and those alive in the next 50 years is enhance the resilience of our communities & infrastructure.”

My instinct tends in the same direction: the climate system has an immense amount of inertia. But, after some thought, I’m inclined to conclude that reality is a bit more messy. We actually do have some meaningful potential influence – albeit limited – over what happens in the coming decades. To understand this it’s useful to focus on three distinctions.

Carbon dioxide versus everything else

Changes in carbon dioxide emissions take a long time to have any impact on the climate system. That’s because of inertia in the both oceans and the atmosphere. But changes in emissions of shorter lived gases can affect the climate system more rapidly. That’s because, even though their impact is still constrained by intertia in the oceans, they aren’t as constrained by inertia in the atmosphere.

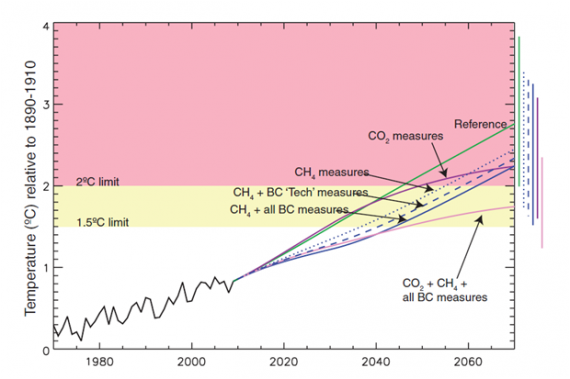

A recent paper in Science by Shindell et al helps shed light on this distinction. It examines a suite of measures aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions along with another suite aimed at cutting emissions of methane and black carbon (referred to as short lived forcers). A plot of projected temperatures taken from the paper is shown below.

Two things immediately become clear. First, consistent with the “informed conventional wisdom”, measures that reduce carbon dioxide emissions have essentially no temperature impact for thirty years. (The actually make things a tiny bit worse, presumably because shutting down coal plants reduces emissions of planet-cooling sulfur dioxide.) Second, though, cutting emissions of methane and black carbon reduces transient temperatures starting right away. By 2050, they cut global average temperatures by about half a degree Celsius relative to trend. Eyeballing the chart in Shindell et al suggests that much of that benefit is realized by 2030. One can reasonably debate whether the modeled emissions cuts are realistic, but as far as the climate system goes, these outcomes are plausible.

Temperature versus sea level

Storm damage is potentially influenced by at least two factors related to climate change: temperature (which can provide storms with energy) and sea level (which can make low lying areas more vulnerable to start with). Everything I’ve just written refers to temperatures. Sea levels, unfortunately, are slower to respond.

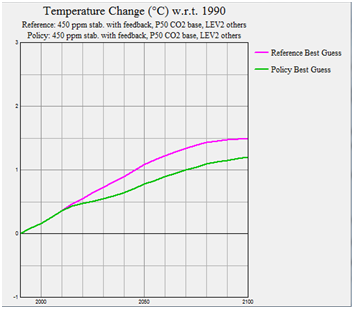

To put some numbers to this, I cooked up a highly unrealistic but still informative scenario. I started with a well known emissions scenario in which global carbon dioxide concentrations ultimately stabilize around 450 ppm (i.e. the sort of scenario that policymakers often talk about). Then I tweak that scenario so that methane emissions plummet in 2015 and stay low through 2100. The projected temperature outcomes (using MAGICC) look like the following:

The temperature rise by 2100 in the case with near-term methane emissions cuts is about 0.3 degrees less than in the case without those cuts. Even more striking, though, is that 100 percent of that temperature reduction is realized by 2050, and that 55 percent of it is realized by 2030.

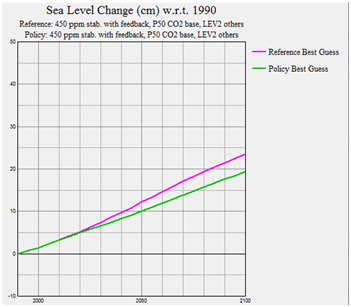

The picture looks quite different, though, for sea level rise:

The sea level rise by 2100 in the case with near-term methane cuts is about 4 centimeters less than in the case without those cuts. Only half of that, though, is realized in 2050, and mere 20 percent of it shows up by 2030.

The details of these projections, of course, are sensitive to the choice of model and the emissions path. But the basic point – you can do considerably more about temperatures than sea levels in the short run – is solid.

Short term versus long term

It is important to keep in mind that the near-term benefits that accrue from cutting short-lived forcers comes at a long-term cost. Shindell et al don’t show projections for the case where their methane and black carbon reducing measures are implemented with a delay. [ML: Important correction appended: They explore this possibility in the online supplementary material. See the comments section for Drew Shindell’s enlightening explanation, which largely tracks with how I see things. My mistake in the original.] If they did, they would find that delaying the cuts, but still implementing them eventually, would help keep down the rate of temperature increase precisely when temperatures are at or near their highest – and thus presumably when climate-sensitive systems are most stressed. Scientists often emphasize that rapid warming can be particularly damaging. The upshot is that near-term measures to cut emissions of things like methane and black carbon, while valuable in suppressing near-term warning, may have a long-term price in climate impacts. I personally think that many near-term steps have benefits – not only for climate but also for local air pollution and human health – that outweigh these downsides. But that doesn’t mean that the downsides don’t exist and shouldn’t be considered.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store