Secretary Clinton’s Valedictory: “Widening the Aperture of Our Engagement”

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Stewart M. PatrickJames H. Binger Senior Fellow in Global Governance and Director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program

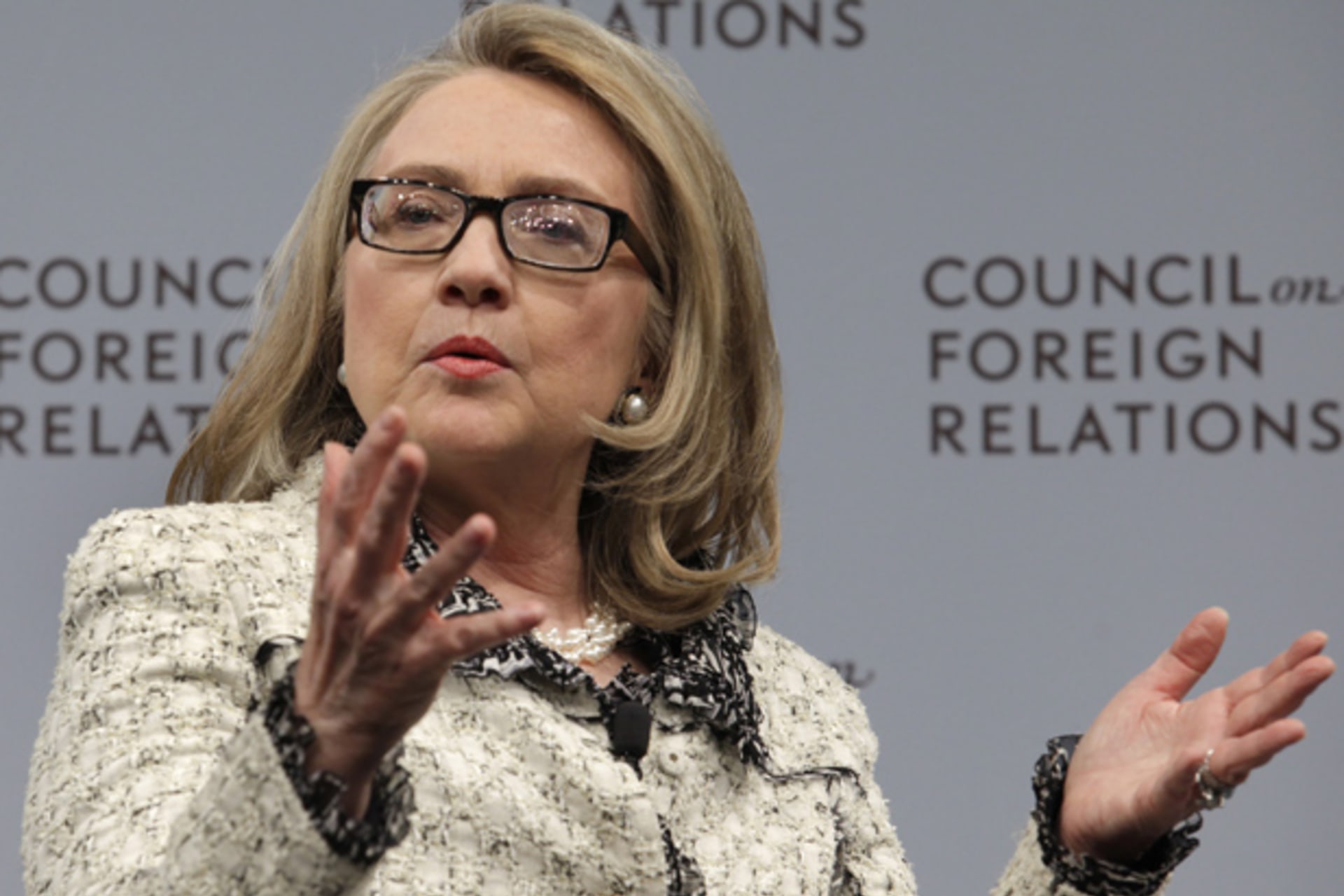

In a valedictory address delivered today at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington, outgoing Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for a new era of American global leadership. The United States remains the world’s “indispensable” power, she insisted. It is the cornerstone of a “just, rules-based international order.” But she warned against complacency. “Leadership is not a birthright,” she insisted. “It has to be earned by each new generation.” To lead in the twenty-first century, the United States will need to “adapt to these new realities of global power and influence,” by exploiting its entire array of policy levers, cultivating diverse partnerships and networks, and forging a “new international architecture” tailored to new global challenges and emerging powers.

Several themes in the secretary’s address stood out:

The architecture of post-World War II order is crumbling: Picking up on a theme of the 2010 National Security Strategy, Secretary Clinton likened our inherited international institutions to the clean lines and columns of the Parthenon, built for an earlier era in which multilateral cooperation could be founded on a handful of great powers. Today, “the geometry of global power is more distributed and diffuse.” As new powers rise and technology empowers nonstate actors, the decaying pillars of world order are straining to manage and contain challenges that spill across borders, from financial contagion to climate change to nuclear proliferation. To adapt to this more complex and chaotic order, the would-be architects of multilateral cooperation must adapt in unconventional ways—taking as their model not the temples of ancient Greece but the work of Frank Gehry.

The future lies in new partnerships and networks: As it has for the past sixty years, the United States will continue to invest diplomatic energy in formal international organizations like the United Nations, the IMF, the World Bank, and NATO. But it should increasingly complement these treaty-based entities with flexible, tailored partnerships and coalitions—like the Global Counterterrorism Forum the Obama administration sponsored with the Turkish government, or the Nuclear Security Summit it convened to help secure the world’s stocks of fissile material. And universal membership organizations would increasingly share space with regional organizations—like the African Union and Arab League—and with subregional entities like the Lower Mekong Initiative that are often more attuned to local realities and willing to invest in solutions. Fortunately, the United States is well-placed to take advantage of this new world, for its “ability to convene…is effective because the United States can back up our words with action.”

Civilian power matters: Military might, the secretary acknowledged, remains central to U.S. credibility with allies and partners. But “hard power” alone remains insufficient. “Smart power” must be the wave of the future. “As the world has changed,” she noted, “so too have the levers of our power.” More than ever, the United States needs to invest in the critical civilian capabilities necessary to conduct “old-fashioned shoe leather diplomacy” and advance development objectives abroad through innovative trade, governance, and aid initiatives. At the same time, Secretary Clinton underscored that the United States “can’t build a set of durable partnerships with governments alone.” Progress will often require diplomats to bypass official channels to engage citizens and civil society groups directly.

Diplomacy must leverage technology: To be effective in the twenty-first century, the secretary observed, “we must widen the aperture of our engagement.” Under her leadership, the State Department has expanded its use of communications technology, including social media. The department has created a virtual war room to counter al-Qaeda’s misinformation on the web, as well as expanded the use of Twitter to explain U.S. policies both to the American people and targeted publics abroad. To be sure, Secretary Clinton acknowledged, the United States has not done enough to communicate its values and reasoning to people abroad. At the multilateral level, the United States remains the foremost champion of internet freedom, helping get dissidents online and blocking misguided efforts that would grant states more power to censor the voices of their populations.

Geopolitics and geo-economics have merged: Conventional distinctions between political and economic concerns are increasingly misplaced, the secretary observed. In Asia, the rapid rise of China risks creating strategic instability and generating insecurity. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, meanwhile, long-term political stability depends in part on regional integration, including the creation of a new “Silk Road.” Likewise, “weak states represent some of our most significant threats.” Securing such countries will require overcoming decades of stalled development.

Human rights values are universal: Secretary Clinton acknowledged the United States’ leading role in promoting, instituting, and defending the human rights of minority communities throughout the world for the last century. However, focusing on an issue that she has championed throughout her career, Secretary Clinton called the universal human rights of women and girls the “unfinished business of the twenty-first century.” As she named Malala Yousafzai in Pakistan, the female rape victims of the war in the Congo, and the women living in fear in Northern Mali, she emphasized that advancing the rights of women everywhere is not just a moral subject, but also an economic and security issue, stating that, “if women and girls everywhere were treated as equal to men in rights dignity and opportunity, we would see economic progress everywhere.” For, argued Clinton, it is no coincidence that the countries that threaten international security also have perilous human rights and weak rule of law.

Secretary Clinton’s remarks resonate with many of the finding of CFR’s International Institutions and Global Governance program. The United States’ most pressing challenges must be confronted with tireless international cooperation—because the United States cannot protect its citizens, promote economic growth, or ensure the well-being of its citizens without painstaking negotiations with global partners. And regardless of the inevitable setbacks and frustrations of multilateralism, it presents the only chance of meeting these challenges. Because achieving these goals “will require every single tool in our toolkit.”