Thailand’s Election Season Gets Even Wilder

More on:

In the run-up to Thailand’s elections on March 24, Thailand’s ruling junta initially seemed to have set the stage for the military and its allies to maintain power, one way or another, over the country. They would do so by ensuring, via the new junta-backed constitution, that no one party or coalition commanded control of the lower house of parliament, allowing pro-military parties to eventually cobble together control. Junta leader Prayuth Chan-ocha this week formally became the candidate for prime minister of the leading pro-regime party, according to the Bangkok Post, after months of playing it coy about whether he would try to remain in charge of the Thai government.

But in recent weeks, the junta’s confidence may well have ebbed. The Puea Thai party and its allies in the campaign grew bolder on the campaign trail, and began to publicly announce their belief that the pro-Thaksin Shinawatra parties could indeed win a majority in the lower house, even though the new constitution seemed to have stacked the deck against them. Initial days of the pre-election period drew enthusiastic crowds, probably a positive sign for Puea Thai and its allies.

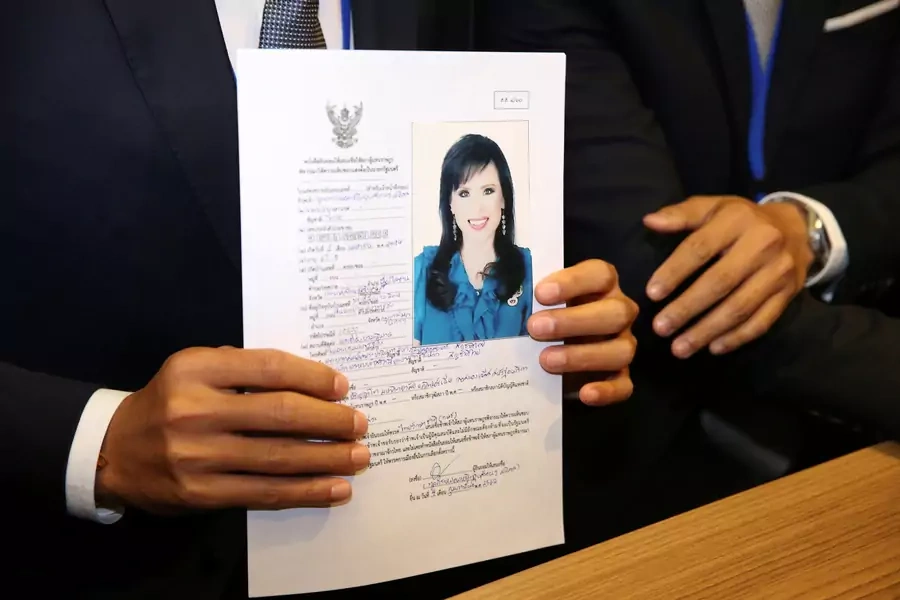

Then, on Friday, the pro-Thaksin parties dropped what appeared to be a bombshell into Thai politics. The Thai Raksa Chart party, widely seen as another pro-Thaksin vehicle in addition to Puea Thai, announced that Princess Ubolratana, the older sister of Thailand’s King Vajiralongkorn, would stand as prime minister on the Thai Raksa Chart ticket. No such senior royal has ever stood for prime minister before, although Ubolratana formally gave up her title in the 1970s to marry a foreigner. Ubolratana long has had a seemingly friendly relationship with Thaksin.

The announcement seemed to presage a tectonic shift in Thai politics, and could potentially lead to a cooling down of what has been one of the most chaotic political climates in Southeast Asia. The princess, who would be a popular choice, would head a government, supported by Thaksin (and presumably approved by the king), and defeat the pro-junta party and its allies. Power would swing away from the military and toward a populist/royalist nexus—although the king certainly has segments of the military who are loyal to him. A pro-Thaksin party would once again be in control in Thailand—pro-Thaksin parties have won every election since 2001—and Thaksin and his sister Yingluck, who was deposed in a coup in 2014, might return to Thailand and even once again play some kinds of roles in Thai politics.

The announcement also held out the promise of some kind of truce in Thai politics. The military would likely lose in the election, and be forced to give up some significant control over politics—and would not launch measures after the election to try to nullify or undermine a win by pro-Thaksin parties. A shift in power away from the military—at least many segments of the military – might allow for national reconciliation among various segments of the Thai population, a government that could stay in power throughout its term, and thus a parliament that could focus on Thailand’s major needs on issues like education and economic reforms.

At the same time, the announcement was still very dangerous for any return to real pluralistic democracy in Thailand. With a princess—even one who renounced her titles—potentially at the head of government, the press, the public, and civil society might be cowed to criticize the government, unsure whether the country’s harsh lèse majesté laws would endanger them for investigating and critiquing a prime minister Ubolratana. How would such a government be held accountable, given lèse majesté laws and the personality cult built around the monarchy?

Then, a few hours ago, the king suddenly announced that it would be inappropriate and contrary to Thailand’s constitution for his sister to participate in politics as a prime ministerial candidate. (Of course, royals have long involved themselves in politics, albeit not openly, in a way that is not normal for a constitutional monarchy.) So, the kingdom was thrown into further turmoil. Did Thaksin, the princess, leaders of pro-Thaksin parties, and the king strike a deal, only for the king to walk away at the last minute—perhaps due to some royalists’ distrust of Thaksin, as Andrew MacGregor Marshall has suggested? Did Thaksin and his allies go forward with their plan with Ubolratana without the king knowing—which would be an unbelievably bold move, given the vast power of the Thai monarchy?

So what happens now? I will cover the scenarios and the election in a further blog post and CFR Explainer.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store