U.S. Fuel Exports: Barrels Away

More on:

Some readers of my last post noted that the decline in oil consumption in the United States since 2007 caused the boom in fuel exports that the country has experienced. Is the export boom due solely to a decline in U.S. demand?

Before getting into that, let’s take a step back and acknowledge that no one’s disputing the reality of the phenomenon itself: U.S. refined product exports have shot upwards in a remarkable way since 2005 or so.

In hindsight, I think I might have undersold the economic magnitude of the trend. Fuel exports brought in an estimated $88 billion to the United States last year, which amounted to four percent of total U.S. exports by value. As a December AP article noted, “Measured in dollars, the nation is on pace this year to ship more gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel than any other single export, according to U.S. Census data going back to 1990.” It continued: “Just how big of a shift is this? A decade ago, fuel wasn’t even among the top 25 exports. And for the last five years, America’s top export was aircraft.”

So soaring fuel exports weren’t even on the radar just ten years ago; now, they’re in the limelight. We can quibble about relative weight of the underlying drivers, but there’s little room to debate their outcome, which is economically notable in its own right.

I’d still argue that the demand-side of the fuel export story is about relative demand growth (or shrinkage, in the case of the United States) in the United States and other neighboring countries, which is how I framed it in my last post. A drop in U.S. demand alone wouldn’t have caused the boom. I would agree with other analysts that, yes, the significant decline in U.S. refined product demand has been of paramount importance in moving the country toward net product exporter status—but without stronger demand growth elsewhere, the boom would not have occurred.

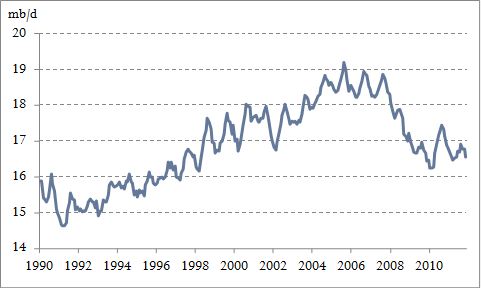

Figure 1 leaves little doubt that U.S. product supplied (the EIA’s approximation of petroleum product consumption) has waned since the onset of the Great Recession in 2007. After climbing to 19.2 million barrels per day (mb/d) in the summer of 2005, it declined steeply into 2010, where it’s more or less plateaued around 17 mb/d (3-month average).

Figure 1. U.S. Product Supplied of Finished Petroleum Products (Rolling 3-Month Average, January 1990–November 2011, EIA)

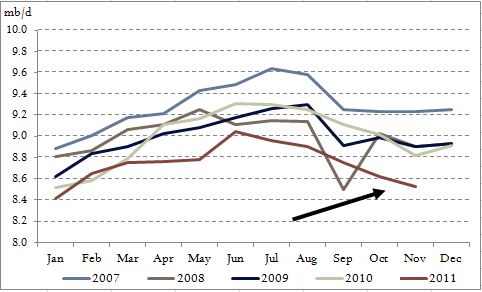

A quick look at U.S. motor gasoline and distillate demand over the last five years shows the extent of the damage—and that demand is still severely impaired. As of the most recent EIA monthly data (November 2011), U.S. gasoline consumption is still shy of last year’s levels for this time of year, let alone those of 2007, which it trails by about 8 percent (Figure 2). High prices at the pump and a sluggish consumer economy have weighed on domestic gasoline demand.

Figure 2. U.S. Finished Motor Gasoline Supplied (2007–2011, EIA)

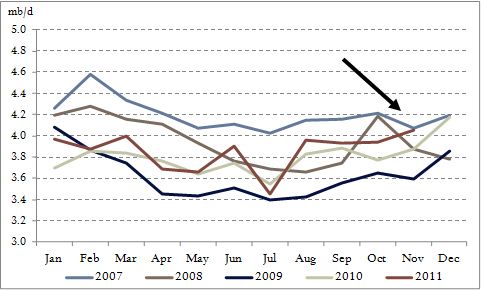

Domestic distillate demand (a type of oil product that includes diesel and heating oil) is in better shape, fluctuating around last year’s seasonal demand, but it’s only barely begun to touch 2007 levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3. U.S. Distillate Supplied (2007–2011, EIA)

But look what’s been happening at oil demand growth in two of the countries I mentioned in my last post, Mexico and Brazil, with ports proximate to the U.S. Gulf. In Mexico, demand rebounded to 2006 levels in no time after a taking a beating in late 2008 (Figure 4). Look at oil demand in Brazil (Figure 5), which is continuing to show robust growth. Demand there is a full 17 percent higher in the fourth quarter of 2011 than over the same period four years earlier.

Figure 4. Oil Consumption in Mexico (2000-2011, IEA)

Figure 5. Oil Consumption in Brazil (2000-2011, IEA)

Consumption growth in these export markets is pulling volumes south from the U.S. Gulf Coast (and to a much lesser extent, East Coast), providing demand for U.S. refineries that are confronting stalled consumption at home. That substitute demand has buoyed profit margins for refiners in the southern United States enough for the boom in fuel exports to occur.

The fact that refineries in the Gulf are adept at processing low-quality oil (heavy and high in sulfur) makes them a natural source for Venezuelan and Mexican crude, among others, which they’re now sending back south and elsewhere as processed fuel.

So will the U.S. fuel export boom hold up in the future? Answering that question requires thinking through several ways in which oil supply and demand trends might shift in the coming years. The outlook depends in large measure on how you think the economies of the United States and Latin America will fare going forward and when you think American drivers will get back to their old ways. In the United States, gasoline prices, unemployment rates, and consumer spending growth will all factor into that calculation. Western Hemisphere refinery capacity additions and oil production growth will also likely matter.

The United States remains the world’s biggest gasoline consumer, guzzling about nine times more than the next biggest, Japan. And it’s still a long way from being a net oil exporter. It may send fuel away, but it still imports a whopping net 9 mb/d of crude oil—more than twenty times the net amount of fuel it exports. But net U.S. crude imports, too, are on the decline for the first time since the 1980s—perhaps the topic for another post.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store