Will Europe Go Green?

Coauthored with Zephira Davis, intern for the International Institutions and Global Governance program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

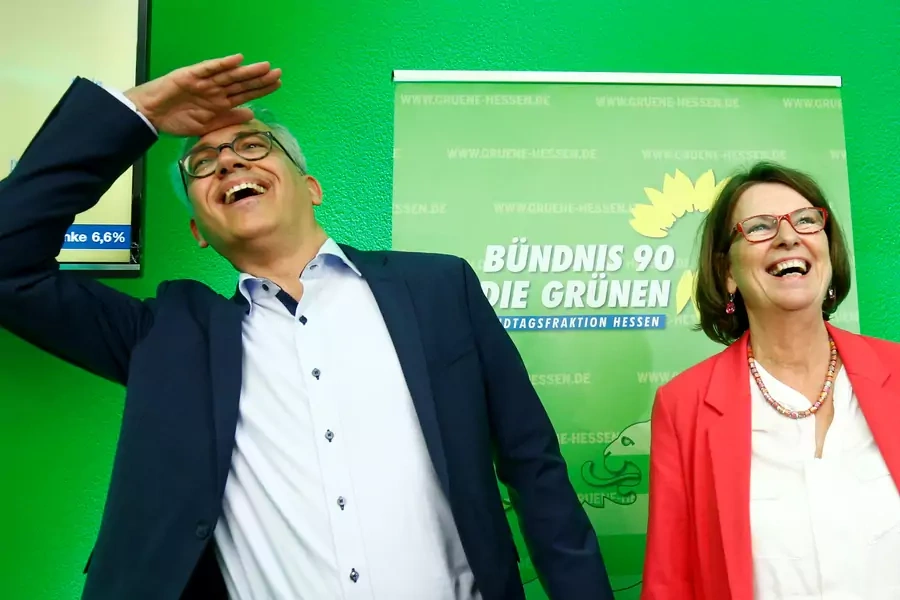

Last week, the German Green party made its second round of unprecedented electoral gains in the state parliamentary elections, achieving 19.8 percent of the vote in Hesse. Conversely, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), suffered a historic loss of 11.3 percent, prompting her departure as party leader after eighteen years and the announcement that she would not personally seek reelection in 2021.

More on:

For the Greens, this is not a flash in the pan. Three weeks ago, they took traditionally conservative Bavaria by storm, winning 17.5 percent of the vote—a sharp increase from 8.6 percent in 2013. The invigorated Greens, much like their Green EU counterparts in Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, are gaining not only in parliamentary seats, but also in credibility and popularity. In doing so, they are making inroads with mainstream European voters, which could have dramatic policy implications on national and European climate policy.

Stirred by the gravity of the recent UN report exposing the looming risks brought on by climate change, popular concerns about environmental policy are surging in Europe. Ironically, U.S. President Donald J. Trump has reinforced this dynamic: his 2017 announcement that he would withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement only pushed EU leaders to reaffirm their commitment to the accords and better coordinate their efforts to mitigate global warming. Meanwhile, European publics are mobilizing, with organized environmental protests across the region and the launching of appeals court proceedings to sue Dutch, French, German, and Swedish governments for non-compliance with EU climate laws.

The rise of Green parties complicates the dominant narrative of contemporary European politics, which sees voters, dissatisfied with traditional center parties, turning toward far-right populist parties like the German Alternative for Germany, Hungarian Fidesz, Dutch Party for Freedom, and Swedish Sweden Democrats. To be sure, the European right gained strength during the 2015 Syrian refugee crisis and Merkel’s suspension of the Dublin Accords, which disaffected conservative European voters. However, with French President Emmanuel Macron’s triumph in 2017 over Marine Le Pen’s far right nationalist agenda, a newer trend has come more into focus. It is a struggle for the European center between traditional conservatives and liberal cosmopolitans—of whom the Greens are the most dynamic force.

Across Europe, formerly robust party loyalties are shifting. Germany is leading the way: in Bavaria, the long-standing conservative governing Christian Social Union (CSU) lost 190,000 votes to the Greens. The CDU’s Hessian loss and Merkel’s timely resignation testifies to this shifting electoral landscape. Significantly, the German state elections saw young voters, usually deemed relatively politically passive, mobilizing to support the Greens and their youthful, charismatic candidates. The Green appeal goes well beyond Germany. A recent poll indicates that 18–26 year-old Europeans believe that climate protection is one of “the most important duties at the European level.”

Hollowed-out center parties increasingly view the Greens as viable coalition partners, with a far more digestible agenda—favoring sustainability, transparency, strong social security, immigration, and European integration—than that of the far right. Given the CSU’s recent losses in Bavaria and the Social Democratic Party’s spiraling poll numbers, the German Greens have an opportunity to expand influence in state parliaments beyond Hesse, allowing them to steer the domestic debate on climate policy. And if Merkel’s governing grand coalition is unable to weather the change in CDU leadership, forcing elections as early as next year, the Greens could well join with the CDU, SPD, or other liberal independent parties to enter a new coalition government.

More on:

Green parties in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg are working to replicate the German model. While they maintain their core progressive values, they are convincing mainstream voters that they are economically prudent as well as eco-friendly. When the Greens first surfaced in the early 1980s, electorates often perceived them as hippy tree huggers narrowly focused on environmental goals. They have since quietly matured into urbane Europeans offering broader policy positions attractive to dissatisfied, centrist voters across EU member states.

The political momentum for green policies is not just confined to northern and central European states. In June, both the Italian and Spanish governments joined seven other EU governments in calling for a faster transition to clean energy and decarbonization. This led to a binding EU agreement intended to increase EU energy efficiency and achieve Paris Agreement commitments. European Green parties across the continent will meet in November 23–25 in Berlin, six months before European parliamentary elections next May. Their growing influence could put additional pressure on the EU to not only force member states to abide by EU regulations, but to simultaneously increase their overall climate targets and considerably reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Over the coming years, the Greens will seek to increase seats—and power bases—both in national parliaments and in the EU Parliament. Offering a pro-EU stance, a humane approach to migration, and clear positions on climate change, biodiversity, and sustainability, Green parties offer voters a healthy and enlightened alternative to both the radical left and right, as well as the scrambling center. Having successfully governed in local and regional coalitions (as in Hesse), they have proved their bona fides and their ability to compromise with more neoliberal, market-oriented parties. This pragmatism demonstrates a growing maturity, including a willingness to make concessions on some issues in return for green priorities. While their natural partners remain the left, experience from Ireland to the Czech Republic show that they are flexible enough to join neoliberal coalitions. At the state level, German Greens have also worked with the CDU and neoliberal Free Democrats in the so-called Jamaica coalition. Alarmed by the AfD—which also improved its showing in the recent German elections—Germany’s traditional parties are increasingly open to alliances with the Greens, who share their commitment to principles of political liberalism.

After years of toiling in relative obscurity, the European Greens are poised to enter the mainstream, as many voters tire of traditional parties and seek an alternative to far right populists. As the European political scene fragments, environmentally concerned, and globally minded Europeans are increasingly attracted to their message. As the Greens increase their political influence, they will have the chance to stimulate meaningful climate policy action—and help build a bulwark against right-wing populism.

Online Store

Online Store