What a Syriza Victory Would Mean for Europe

This weekend’s snap election in Greece could determine the direction of the country’s future, as well as shift the economic course for the rest of the eurozone, says expert Eleni Panagiotarea.

January 23, 2015 12:27 pm (EST)

- Interview

- To help readers better understand the nuances of foreign policy, CFR staff writers and Consulting Editor Bernard Gwertzman conduct in-depth interviews with a wide range of international experts, as well as newsmakers.

With the radical-left Syriza party gaining in the polls ahead of this Sunday’s snap parliamentary elections, its firebrand leader Alexis Tsipras is now being viewed by many watchers as Greece’s presumptive prime minister. Eleni Panagiotarea, a fellow at the Athens-based think tank ELIAMEP, says that the young politician could find himself "trapped" by his own campaign rhetoric should he take office. "Tsipras has portrayed himself as a leader of the Left, not just for Greece, but also for the entire eurozone. It will be hard for him to make a U-turn with lenders without losing credibility both at home and abroad." But Panagiotarea also acknowledges that the election’s outcome could have huge ripple effects across the currency union. "A Syriza victory could potentially shift the macroeconomic agenda for all of Europe," she says.

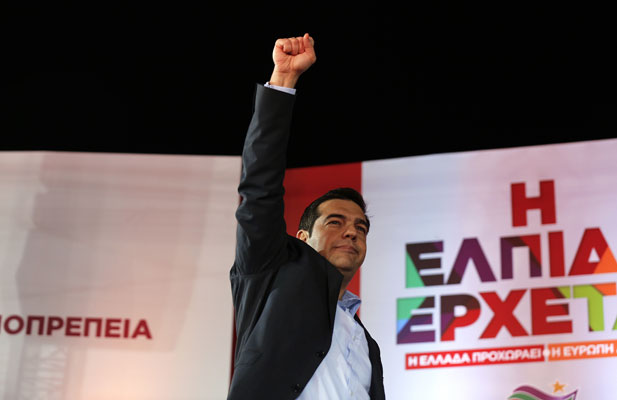

Alexis Tsipras told crowds gathered in Athens that an end to "national humiliation" was near after opinion polls showed his Syriza party pulling ahead days before an election. (Photo: Yannis Behrakis/Courtesy Reuters)

Alexis Tsipras told crowds gathered in Athens that an end to "national humiliation" was near after opinion polls showed his Syriza party pulling ahead days before an election. (Photo: Yannis Behrakis/Courtesy Reuters)Right now, polls point to a victory for Syriza. Will a Syriza win mean an end to austerity in Greece?

More on:

"Tsipras is trapped by his own rhetoric. He has portrayed himself as a leader of the Left, not just for Greece, but also for the entire eurozone. It will be hard for him to make a U-turn with lenders without losing credibility both at home and abroad."

Greece, a member of the eurozone, is currently implementing an economic adjustment program in exchange for two aid packages worth €240 billion ($300 billion). After five years of austerity, GDP has shrunk by 25 percent, total household income has been reduced by 30 percent, and the unemployment rate hovers at 25 percent. Ordinary Greeks have paid a high price, and unfortunately, the most vulnerable were not protected (even though protecting them was an explicit commitment in both bailout agreements). Syriza has indeed pledged to end austerity. However, their proposals to up the minimum wage, increase public expenditure, expand the public sector payroll, and abandon privatization sound more like promises to return to the "good old days" of state largesse. These proposals are also at odds with the other Syriza pledge to balance budgets and keep Greece in the eurozone.

The simple truth is that Greece cannot currently fund itself on the markets. Its repayment obligations in 2015 alone amount to €22.5 billion ($25.3 billion), and the European Central Bank has stated time and again that it will only provide liquidity to Greek banks as long as the country remains in the [economic adjustment] program. So, ending austerity in Greece is a complicated process that will require more than an election and change in government.

To truly end austerity, the next government will need a long-term plan for generating growth, attracting investment, and promoting exports. The new administration will need to wean the economy off the public sector. Right now, Syriza is promising to reenergize it.

In his campaign, Alexis Tsipras has promised to renegotiate Greece’s bailout. What do you think his strategy will be with regard to renegotiating bailout terms if he becomes prime minister?

More on:

As election day approaches, we’ve been watching a game of chicken unfold. Tsipras believes that the troika of the European Commission, IMF, and ECB will blink first because the current economic plan being implemented in Greece is not working and because these institutions will not want to be held responsible for a "Grexit" [a Greek exit from the eurozone].

Tsipras and his party have faith in their "Plan A": renegotiate and gain substantial concessions. They have no "Plan B." Tsipras’s pledge to renegotiate on his terms explains Syriza’s meteoric rise. But what happens if and when Tsipras takes office? As prime minister, heroic defiance will no longer be enough. Given the constraints, will he be able to sit down at the bargaining table with Greece’s creditors and negotiate a new program of debt relief? If he has to modify his stance, will he be able to maintain control over his party (including the far-left faction, which wants significant debt relief)? In many ways, Tsipras is trapped by his own rhetoric. He has portrayed himself as a leader of the Left, not just for Greece, but also for the entire eurozone. It will be hard for him to make a U-turn with lenders without losing credibility both at home and abroad.

One way out would be if Syriza had to form a coalition government, which could provide valuable political cover. It would enable Tsipras to negotiate with lenders while saving face with his constituents. It could also help tone down the more radical elements within the Syriza party, which are also the most disciplined. Tsipras, however, has repeatedly asked for the Greek people to give him an outright majority.

So far, the troika has been adamant that Greece must observe previously negotiated terms. How much leverage does Tsipras have to renegotiate the bailout agreements?

For the troika, bailout agreement commitments are national commitments, they are not government commitments. So you can change governments but not national commitments. If goodwill prevails, then some fine-tuning of the bailout conditions might be possible. Tsipras could start by challenging the specifics of the program. He can point out that the fiscal consolidation plan is not realistic, with the expectation that primary surpluses of 4.5 percent will be maintained for ten years. Growth projections remain too sanguine. He can also remind parties of the November 2012 Eurogroup agreement, which offered debt relief if Greece reached a primary surplus. On the other hand, he could just refuse to negotiate, since he has repudiated the program in his entirety. But time is running out, because the extension of the current program expires on February 28. What is at stake is nothing less than the Greek state’s liquidity.

"If Syriza sticks by its pledge to ’tear up’ the bailout agreement, we will probably see zero, or close to zero, flexibility on the part of the European Commission, ECB, and IMF."

If Syriza sticks by its pledge to "tear up" the bailout agreement, we will probably see zero, or close to zero, flexibility on the part of the European Commission, ECB, and IMF. They will not want to jeopardize their status and credibility on Greece. These institutions are also very wary of setting a precedent for fear that other eurozone-member countries feeling the fiscal squeeze will say, "Look what you’ve done for Greece. Why can’t you do something similar for us?" So I think it will be very difficult to radically alter the terms of Greece’s bailout agreements.

Could this game of chicken precipitate a "Grexit"?

A "Grexit" would be the worst possible outcome for all the players in the game. Greece can’t really go back to the drachma—not with its chronic low competitiveness, weak productive structure, and continued reliance on financing from abroad. Furthermore, its European partners have said repeatedly that membership in the eurozone is irreversible. So to move from that position to a "Grexit" would not just be a major blow to their credibility, but it would also signal that their house was neither cohesive nor in order. This would invite trouble on an immense scale.

Could a Syriza victory spur anti-austerity movements across other eurozone countries?

A Syriza victory could potentially shift the macroeconomic agenda for all of Europe. A wave of protest parties is becoming increasingly visible, challenging the national and European political establishment. Stagnating economies and high unemployment rates have made ordinary citizens question the current orthodoxy of austerity. They want to see their democratically elected governments gain more control over their economic policies. As "real convergence" is thrown out of the window and eurozone membership becomes something to be endured (rather than shared), the eurozone’s long-term survival cannot be seen as a given. We need a positive narrative about growth, jobs, and future prospects.

Do you think the systemic risk has been minimized, or could a "Grexit" unleash a "Lehman moment" that would spur banking crises and domino bankruptcies across Europe?

Some politicians and policymakers have recently argued that Greece no longer poses a systemic risk to the currency union and that the potential ripple effects of a "Grexit" have been contained. It is true that Greek assets and Greek bonds have decoupled from the rest of the periphery. European banks are no longer exposed to Greek assets, and there are significant financing tools on the table that can act as deterrents and contain market pressures at an early stage. At the same time, a "Grexit", if it happens, would highlight all that is wrong with the eurozone: stagnation, deflation, high unemployment, and rising public debt levels. This could, in turn, tempt investors to have a go at the next "weak link": Portugal, Ireland, Spain, or even Italy. Also on a political and symbolic level, a "Grexit" would signify to the rest of the world that the currency union had de facto split into the eurozone of the core and the eurozone of the south. That could prompt an existential crisis with many asking, "What is it that binds this particular monetary union?"

Do you think the ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) announcement will shift the political calculus in Greece?

The QE program had already been discounted by analysts and the markets. The Greek elections might have been a factor when fine-tuning and readjusting the program’s contours, but the ECB’s Governing Council acts independently of individual countries’ domestic politics. However, the process by which the ECB decides the ways in which the program will be run and determines eligibility for program participation could turn up the pressure for any future Greek government.

Online Store

Online Store