- Iran

- Israel-Hamas

-

Topics

FeaturedIntroduction Over the last several decades, governments have collectively pledged to slow global warming. But despite intensified diplomacy, the world is already facing the consequences of climate…

-

Regions

FeaturedIntroduction Throughout its decades of independence, Myanmar has struggled with military rule, civil war, poor governance, and widespread poverty. A military coup in February 2021 dashed hopes for…

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

FeaturedDuring the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised that his administration would make a “historic effort” to reduce long-running racial inequities in health. Tobacco use—the leading cause of p…

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Terrorism and Counterterrorism

Violence around U.S. elections in 2024 could not only destabilize American democracy but also embolden autocrats across the world. Jacob Ware recommends that political leaders take steps to shore up civic trust and remove the opportunity for violence ahead of the 2024 election season.Contingency Planning Memorandum by Jacob Ware April 17, 2024 Center for Preventive Action

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023 Academic and Higher Education Webinars

-

Events

FeaturedJohn Kerry discusses his work as U.S. special presidential envoy for climate, the challenges the United States faces, and the Biden administration’s priorities as it continues to address climate chan…

Virtual Event with John F. Kerry and Michael Froman March 1, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

The Kurds’ Long Struggle With Statelessness

The Kurds are one of the world’s largest peoples without a state, making up sizable minorities in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. Their century-old fight for rights, autonomy, and even an independent Kurdistan has been marked by marginalization and persecution.

Middle East Reconfigured After WWI

The 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement divides the Middle East into British and French zones of influence and delineates the borders of the modern Middle East. Following World War I, the Treaty of Sevres [PDF], signed in 1920, dissolves the Ottoman Empire and proposes the creation of an autonomous Kurdish state. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Turkey’s new leader, rejects Sevres. It is replaced in 1923 by the Treaty of Lausanne, negotiated with the new Turkish government, which omits any reference to a Kurdish homeland. The Kurds, inhabiting previously Ottoman territories, are dispersed across the newly demarcated borders of Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, and repeatedly revolt against the respective authorities.

Iranian Kurds Establish Republic of Mahabad

Kurds establish the Republic of Mahabad, a short-lived, independently governed state in Kurd-inhabited territories of Iran that came under Soviet control during World War II. Iran reoccupies Mahabad after the Soviet withdrawal in December 1946.

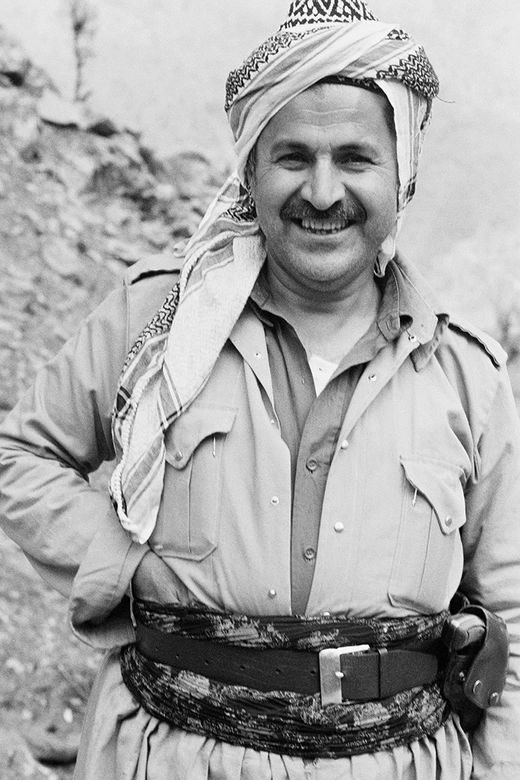

Barzani Founds Kurdish Party in Iraq

Mustafa Barzani, considered the father of Kurdish nationalism, creates the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iraq while in exile in the Republic of Mahabad. Later renamed the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), it was the only Kurdish party in Iraq until the 1970s. It remains the dominant Kurdish party.

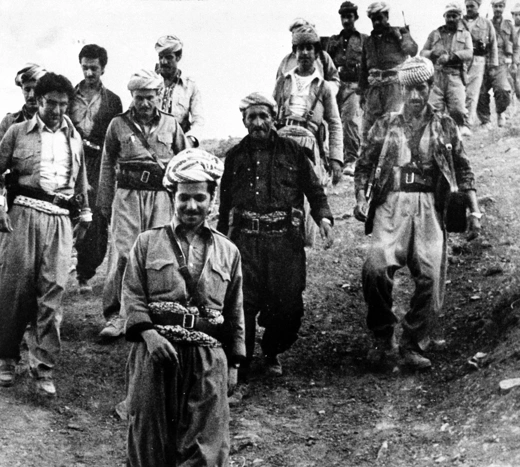

Iraqi Kurds Rebel

Following unfulfilled promises of autonomy under the rule of Iraqi Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim, Barzani launches a Kurdish rebellion. It continues throughout the decade against successive Iraqi regimes. Iraq’s Baath party, a regional branch of the pan-Arabist socialist movement, comes into power in 1968. In March 1970, the Baathist government details plans for Kurdish autonomy. They are not implemented, and fighting resumes in 1974.

Syria Strips 120,000 Kurds of Citizenship

In a census of Syria’s Al-Hasakah Governorate, Kurds who cannot prove their residence in Syria prior to 1945 and those who fail to participate are stripped of their citizenship, rendering them stateless and unable to travel. These Kurds and their descendants are unable to vote, own property or businesses, or legally marry. In April 2011, amid an intensifying uprising, President Bashar al-Assad promises some “unregistered” Kurds citizenship.

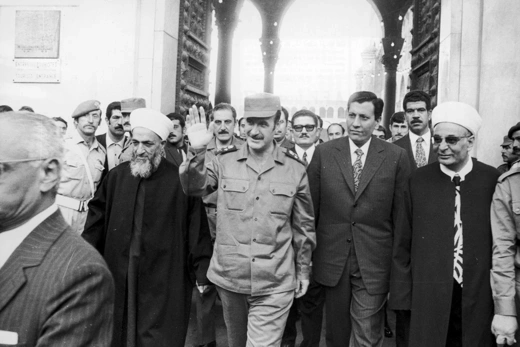

‘Arab Belt’ Established in Syria’s Northeast

Syrian leader Hafez al-Assad establishes a so-called Arab belt along the border with Turkey, displacing Syrian Kurds. The move is designed to weaken Kurdish dominance of resource-rich areas. Assad, a Baathist, seized power in 1970, seven years after the party came to power in a coup.

PKK Founded

Abdullah Ocalan founds the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) as a Marxist organization with the aim of establishing an independent Kurdistan in Turkey’s southeast. Though initially not taken seriously, the PKK steadily gains adherents among disenfranchised Kurds. A military coup takes place in Turkey in 1980, and the PKK leadership flees to Syria. In 1984, the organization begins to use violence against the state and terrorist tactics, and the United States designates it as a terrorist organization in 1997. At least forty thousand people have been killed in the Turkish-Kurdish conflict to date, though experts say the overall toll is difficult to determine. Kurds have made up the overwhelming majority of victims.

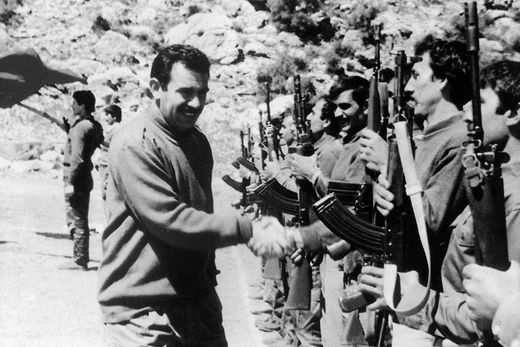

Baathists Arabize Northern Iraq

With the collapse of an autonomy agreement in 1974, Iraq’s Baathist regime, seeking to consolidate government control over the oil-rich regions in the country’s north, displaces hundreds of thousands of Kurdish inhabitants of the area and replaces them with Arabs from central and southern Iraq. Iraqi Kurds, supported by Iran and the United States, revolt against the Baathist regime.

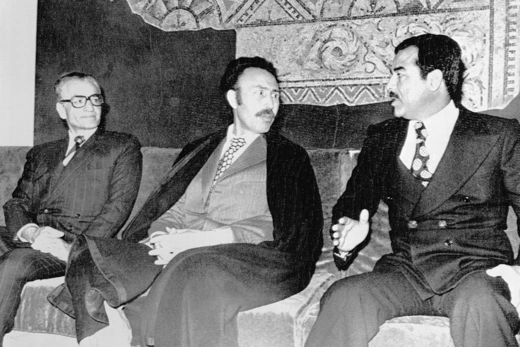

Iraq, Iran Sign Algiers Accord

In Algiers, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein recognizes Iranian sovereignty [PDF] over half of the Shatt al-Arab estuary in exchange for Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s commitment to stop assisting Iraqi Kurds. The United States, which has been providing money and arms to Iraqi Kurds since 1972 at Iran’s request, withdraws its support for the Kurds. The Kurdish rebellion collapses soon after.

PUK Founded

Divisions among Iraqi Kurds emerge after the rebellion’s collapse. Denouncing Barzani as reactionary, Jalal Talabani splinters from the KDP to establish the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). Political allegiances largely follow the fault lines between the two major Kurdish dialects, as the PUK establishes its stronghold in the Sorani-speaking regions of central Iraq and the KDP maintains its center of activity in the northern, Kurmanji-speaking districts.

Barzani’s Son Inherits KDP Leadership

Masoud Barzani takes on the presidency of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iraq after the death of his father, Mustafa. Barzani has been reelected as KDP president at every subsequent party congress to date. In 2005, he is elected president of the semiautonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Kurds Rebel Following Iran’s Islamic Revolution

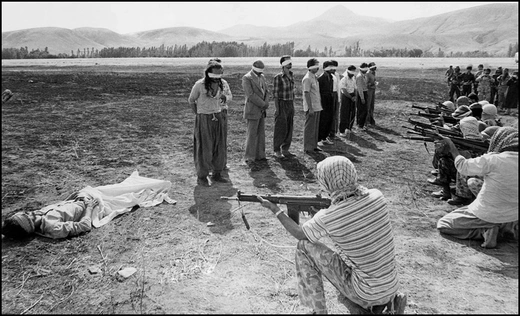

Hoping to achieve greater autonomy under the rule of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Kurds are initially supportive of the January 1979 Islamic Revolution, but they rebel against the new regime [PDF] when their demands go unmet. Khomeini declares a holy war against the Kurds on August 18. A military campaign to exert control over Kurdish regions results in hundreds of deaths, systematic arrests, and the banning of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI).

Kurds Take Up Arms in Iran-Iraq War

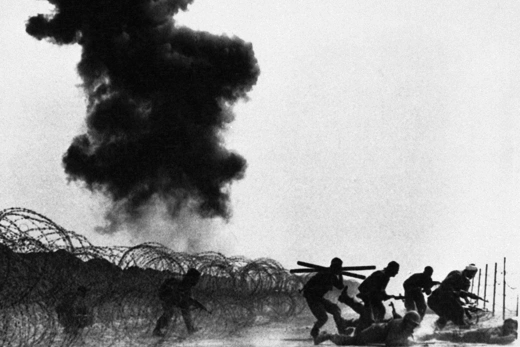

Saddam enlists and arms Iranian Kurds, while Iraqi Kurds once again rebel against Baghdad with Iran’s support. Both governments view their Kurdish populations as collaborating with the enemy and retaliate against civilians, destroying villages and carrying out summary executions. These cross-border alliances also deepen divisions and spur clashes between Iranian and Iraqi Kurds.

Saddam Unleashes Genocide

From February to September, Saddam carries out the al-Anfal (“the spoils”) campaign, known as the Kurdish Genocide, which includes mass killings, the destruction of thousands of villages, and the use of chemical weapons against civilians. An estimated 50,000 to 180,000 Iraqi Kurds are killed and tens of thousands displaced. On March 16, as many as five thousand Kurds are killed in a sarin and mustard-gas attack on the town of Halabja.

No-Fly Zone Enforced Over Iraqi Kurdistan

After Iraqi forces are defeated by U.S.-led forces and leave Kuwait, Saddam cracks down on rebelling Iraqi Kurds. More than one million Kurds flee to Turkey and Iran, and hundreds of thousands of others are internally displaced, triggering a humanitarian catastrophe. In response, a U.S.-led coalition carries out Operation Provide Comfort and the subsequent Operation Northern Watch, supplying humanitarian aid and enforcing a no-fly zone over Iraqi Kurdistan, allowing the Kurds to return. With the erosion of the central government’s hold on the north, Iraqi Kurds gain de facto autonomy. They elect the first Kurdistan Regional Government and National Assembly in 1992.

Iraqi Kurds Fight Civil War

The two leading political parties in Iraqi Kurdistan, the PUK, led by Talabani, and the KDP, led by Barzani, fight a civil war that kills more than two thousand Kurds. In 1996, Barzani appeals to Saddam for assistance as Talabani’s PUK receives support from Iran. The conflict ends with the U.S.-brokered Washington Peace Agreement on September 17, 1998.

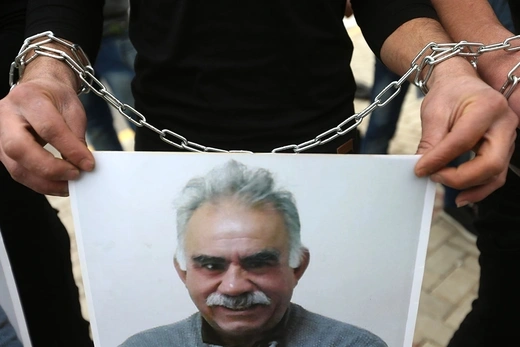

PKK’s Ocalan Arrested

In 1980, PKK leader Ocalan finds refuge under Hafez al-Assad’s protection in Syria. In 1998, under military pressure from Turkey, Syria signs the Adana Agreement, which commits to ending support for the PKK, and Ocalan flees. With U.S. help, Ocalan is apprehended by Turkish forces in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1999, and he is sentenced to life imprisonment for treason. Ocalan’s arrest sparks Kurdish protests throughout Turkey and across Europe. Following his capture, the PKK declares a unilateral cease-fire, which ends in June 2004.

U.S. Invasion Paves Way for KRG Autonomy

U.S. forces invade Iraq, toppling Saddam. Kurds play a central role in drafting the interim Iraqi constitution, which recognizes the autonomy of the KRG within the new federal system. Talabani is named the first Kurdish president of Iraq. Kurdish parties participate in 2005 elections and are included in Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s unity government in 2006. The KRG remains a part of the federal Iraqi state through the present.

Turkey Introduces Reforms

Working toward EU membership, Turkey introduces legislative and constitutional reforms that expand Kurdish political and cultural rights, such as permitting the use of the Kurdish language in national television broadcasts. In 2009, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) government announces a “Kurdish Initiative” with plans for further reforms, which wavers in response to nationalist backlash.

Syrian Kurds Found PYD

Affiliated with the militant Turkish PKK, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) is founded in Syria. Its platform calls for the recognition of Kurdish rights and regional autonomy. Its loyalty to the PKK puts it at odds with other Syrian Kurdish parties, as well as the Barzani-led KRG in Iraq.

Kurds Stage Mass Protests in Syria’s Qamishli

Syrian Kurds take to the streets in Qamishli after Syrian forces open fire on a procession mourning nine Kurdish youths who died in a brawl between Arabs and Kurds at a soccer match. Syrian forces crack down on mass demonstrations, which spread to neighboring towns as well as Aleppo and Damascus, and also inspire protests by Kurds in Europe.

PJAK Emerges in Iran

The Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan (PJAK), a PKK-inspired guerrilla group that claims to have three thousand fighters, takes up arms against the Iranian state. The United States designates PJAK a terrorist organization in 2009 over its ties to the PKK. In 2011, PJAK signs a cease-fire agreement with the Iranian government following a massive military campaign that kills hundreds.

Syria’s Assad Grants Some Kurds Citizenship

Seeking to court Kurdish support amid an uprising, embattled President Bashar al-Assad issues Decree 49, which grants citizenship to Kurds who were registered as foreigners in the 1962 census. Kurds who were never registered remain stateless.

Turkey, KRG Grow Closer

Reversing earlier policy, Turkey deepens ties and energy cooperation with Iraqi Kurds following the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq. In April 2011, Prime Minister Erdogan becomes the first Turkish leader to visit Iraqi Kurdistan. Following this is a historic visit by KRG President Barzani to Diyarbakir, in southeastern Turkey, in November 2013. Meanwhile, in May 2012, the parties agree to build three pipelines to bring oil and gas from the KRG to Turkey.

Turkey, PKK Renew Peace Talks

Direct official negotiations between the Turkish government and jailed PKK leader Ocalan seek to bring an end to three decades of conflict, which has killed an estimated forty thousand people. Secret negotiations in Oslo, Norway, that began in 2009 were revealed when a tape was leaked in 2011.

Kurds Declare Autonomy in Northern Syria

Amid the country’s civil war, the Kurdish PYD unilaterally declares three autonomous cantons in Syria’s north known as Rojava (Western Kurdistan).

KRG Bypasses Baghdad to Sell Oil

Iraqi Kurdistan begins direct energy exports, raising concerns in Baghdad and Washington that the oil revenue could allow Kurds to seek independence. In a sign of warming relations, Turkey is among the KRG’s oil buyers. Baghdad retaliates by blocking the KRG’s 17 percent share of federal revenues, leading to a fiscal crisis for the Kurdish region. In a December 2014 agreement, Kurds recommit to sell oil through Iraq’s national oil-marketing company in exchange for resumed federal revenue sharing.

Rise of Islamic State

Aiming to establish a caliphate in the Levant, the self-proclaimed Islamic State, a Sunni Muslim jihadi group, takes control of large swaths of Iraq, including Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, and territory controlled by the semiautonomous KRG. Iraqi national forces and the KRG’s peshmerga buckle in the face of Islamic State advances. However, in June, the peshmerga take control of the long-disputed, oil-rich city of Kirkuk.

Kurds Battle Islamic State in Kobani

Islamic State militants attack Kobani, a strategically located Syrian Kurdish town that borders Turkey and is controlled by the PYD. As the PYD defends itself, the United States comes to its support with heavy air strikes and airdrops of armaments. U.S. support for the PKK’s affiliate leads to a crisis in U.S.-Turkey relations.

Syrian Kurds Consolidate Territory

YPG forces and allied Arab rebels cap a monthslong offensive against the Islamic State by capturing Tel Abyad, a Syrian town along the border with Turkey that was a transit point for the Islamic State’s capital, Raqqa. The campaign expands the territory controlled by the Kurds in northern Syria and consolidates it from three noncontiguous regions to two.

Turkey Attacks Islamic State, PKK

Turkey joins the fight against the Islamic State and begins bombing the group’s positions in Syria, while Turkey grants the United States access to its Incirlik Air Base to support air raids on Islamic State targets. At the same time, Turkey attacks PKK targets in Iraqi Kurdistan, ending a two-year cease-fire. Earlier in the week, a suicide bombing attributed to the Islamic State kills thirty-two people in Suruc, a Kurdish-majority Turkish town on the Syrian border.

Turkey Intervenes in Syria

After years of supporting Syrian rebels, Turkey intervenes directly in northern Syria, backing Arab fighters against the Islamic State. Part of the motivation is to restrict Syrian Kurds from connecting their two cantons, and that goal was largely achieved during the seven-month operation. The Turkish deployment of troops and advisors halts a Kurdish advance west of the Euphrates River and creates a complex front line that includes the two opposing U.S. allies and Russia- and Iran-backed forces loyal to the Assad regime.

U.S. Arms Syrian Kurds

U.S. President Donald Trump approves a plan to arm the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a militia dominated by the YPG, directly via the Defense Department as the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State prepares to seize Raqqa. The move angers Turkey, which has previously tried and failed to promote its proxies to take the lead in Raqqa.

Iraqi Kurds Vote for Independence

Voters in Iraqi Kurdistan overwhelmingly choose independence in a referendum held by regional officials despite objections by the Iraqi government. Baghdad rejects attempts to break up the state, as well as the KRG’s insistence on holding the vote in the disputed oil-rich territory of Kirkuk. While KRG President Barzani hoped a resounding “yes” vote would bolster the KRG in negotiations with Baghdad over separating from Iraq, the central government refuses talks, and instead threatens to isolate the region, as do Iran and Turkey.

Turkish Troops Capture City Held by Syrian Kurds

After a monthslong battle that kills dozens of civilians, Erdogan—now Turkey’s president—says Turkish forces and allied Syrian rebels have gained “total control” of Afrin, a city in northern Syria previously held by YPG forces. Tens of thousands of civilians flee their homes, according to the United Nations.

Syrian Kurds Declare Victory Over Islamic State

The SDF take control of areas around the Syrian town of Baghouz, near the Iraq-Syria border, the last populated area held by the Islamic State. An SDF spokesperson declares the “total elimination of [the] so-called caliphate,” and U.S. officials say it marks the end of the Islamic State’s territorial rule. But they warn that Islamic State fighters still pose a threat.

Turkey Advances Into Northern Syria

President Trump announces the exit of the nearly two thousand U.S. troops from northern Syria and, almost immediately after, Turkish forces cross the border into Syria with the aim of pushing Kurdish forces out of a twenty-mile-deep buffer zone. Hundreds of thousands of people flee in the first few days of the invasion. The SDF turns to the Syrian government for help, allowing its forces to reenter areas held by the Kurds for years. The offensive ends in a deal that sees Kurdish forces pull back from the border, with Russian and Turkish forces jointly monitoring the retreat. Meanwhile, Trump revises his order to remove all U.S. troops, leaving several hundred of them to protect northeastern Syria’s oil fields.

Operations Claw-Eagle and Claw-Tiger Launched

Following alleged attacks by the PKK on Turkish bases, Turkey begins air and land campaigns against PKK targets in Iraqi Kurdistan. Turkey had begun growing its military presence in Iraq the previous year, following the killing of a Turkish diplomat that Ankara blamed on the PKK. Baghdad criticizes Ankara’s moves as an assault on Iraq’s territorial integrity, while the KRG, which has strong economic ties with Turkey, expresses concerns over civilian casualties. At least seven civilians are reportedly killed. Still, Turkey sets up new bases in Iraqi Kurdistan, something the KRG has long allowed Ankara to do.

War Crimes Against Syria’s Kurds Reported

UN investigators release a report alleging that the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) committed war crimes in northern Syria. The inquiry, conducted over the first half of 2020, finds that the SNA carried out murder, torture, and arbitrary detention, as well as coerced primarily Kurdish residents to flee their homes. The UN team also accuses Kurdish forces of unlawful detention and recruitment of children. Videos shared on social media appear to show the SNA committing what U.S. officials say likely constitute war crimes. Turkey calls the claims against its allies “unfounded” and says the UN Human Rights Office’s response to the report unfairly criticizes Ankara.

Anti-PKK Operation Tests U.S.-Turkey Ties

A Turkish military mission to rescue thirteen of its nationals captured by PKK forces fails, with all of the captives found dead. Ankara says they were executed by the PKK, but the guerrilla group blames a Turkish bombing campaign. A U.S. State Department statement on the incident does not assign blame to the PKK, prompting backlash in Turkey. Secretary of State Antony Blinken later walks back the assertion of doubt in the initial statement. Still, the rift between Washington and Ankara deepens.

Rockets Strike U.S. Base in Erbil

Rockets launched from within Iraqi Kurdistan strike the regional capital, Erbil, targeting an air base that hosts forces of the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State. The attack injures at least nine people, including an American soldier, and kills a Filipino civilian contractor. A group calling itself Saraya Awliya al-Dam claims the attack and says it will continue to target U.S. forces, particularly those in Iraqi Kurdistan. Iraqi officials suspect the group is connected to Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces, an Iran-backed paramilitary collective. Rocket attacks by Iranian proxies are rare in KRG territory; the last such attack occurred in September 2020.

Iran Attacks Exiled Kurds in Iraq

Iran bombards Kurdish opposition groups in northern Iraq for supporting anti-government protests roiling Iran. The demonstrations were sparked by a Kurdish Iranian woman’s death in police custody. Tehran attributes the unrest to interference by foreign governments, as well as several exiled Kurdish political parties. The missile and drone strikes kill at least twenty people within two months and injure dozens more; the casualties include civilian women, refugees, and children. Iraq’s foreign ministry calls the attacks a violation of national sovereignty and vows a diplomatic response.

Turkey Launches Operation Claw-Sword

Turkey begins an air offensive targeting Kurdish militants in Iraq and Syria in retaliation for a bombing that killed six people and injured more than eighty others in Istanbul on November 13. Ankara blames the PKK and its U.S.-backed Syrian allies for the attack. President Erdogan reiterates threats of a ground invasion of Syria. He also says Turkey will no longer tolerate Western powers’ distinction between Syrian Kurdish rebels and the PKK.

Online Store

Online Store