Why the United States Needs a Real Corporate Tax Cut

More on:

There is no morally defensible reason for cutting corporate taxes at a time of deepening national debt that will require greater burdens for all Americans, either through higher taxes on income and consumption or lower spending on entitlements, defense, or other government programs. Unfortunately, it is a practical necessity.

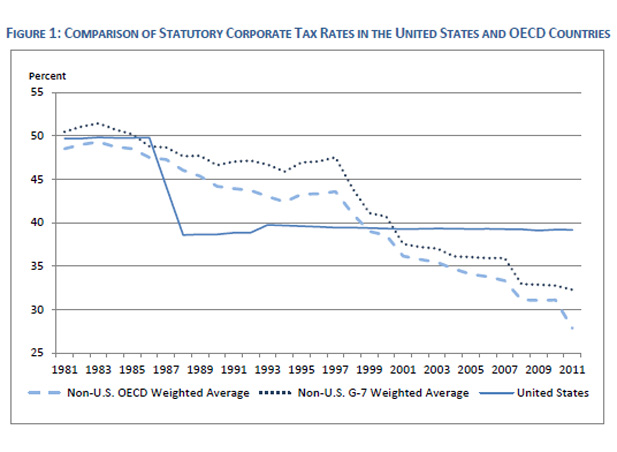

Technology and trade liberalization have created a global competition for investment. Multinational companies considering their investment alternatives weigh many factors, but the tax burden is high on the list. It is no coincidence, as the chart below published today by the Treasury Department shows, that corporate tax rates began to fall in the 1980s as global trade accelerated, and then fell even more sharply in the mid-1990s, coincidental with the creation of the World Trade Organization and big advances in transportation and communications technology. The United States was one of the few countries that did not jump on the bandwagon. It has refused to recognize what has been obvious for many years to smaller countries with fewer of their own multinational companies--corporate capital is a “mobile factor” that forces countries to compete for investment.

Chart source: The President's Framework for Business Tax Reform

That mobility is at the heart of why President Obama’s Framework for Business Tax Reform, spelling out the Obama administration’s corporate tax priorities, is such a disappointing proposal. Except at the margins in relation to the manufacturing industry, there is little in the proposal that would make the United States a more profitable place to invest, and some that could do the opposite.

In the first place, as the Treasury acknowledges, the Obama administration is not really proposing a corporate tax reduction. It would lower the statutory federal corporate tax rate from 35 percent--soon to be the highest in the developed world--to 28 percent by closing an array of loopholes and tax deductions and increasing taxes on overseas profits. Even if the rate reduction were a real tax cut, it would be modest. As it is, the result would only be to benefit some industries that pay high effective rates under the current system, such as transportation and manufacturing, at the expense of others that pay lower effective rates, such as drug and biotech companies. While this could well be fairer and less distortive than the current system, it would do nothing to close the broader U.S. competitive disadvantage.

Even more disappointing is the president’s proposal to discourage overseas investments by U.S.-headquartered multinational companies. As it now stands, the United States nominally has a worldwide tax system in which companies are taxed at the U.S. rate on their global profits (minus deductions for taxes paid abroad). In reality, the United States has a distorted territorial system in which, because the U.S. tax is only imposed when companies repatriate their profits, there is an enormous incentive to earn and/or shift profits offshore. Irwin Jacobs, co-founder and former chairman of Qualcomm, the San Diego technology giant, noted at a Brookings forum that the company currently has about $22 billion of cash on its books, $16 billion of which is held abroad. The domestic cash can be used for a variety of purposes, including dividends to shareholders or buybacks. The foreign cash can only be invested abroad, or returned home and taxed heavily. Guess which the company will likely choose?

The Obama administration’s proposal to deal with this dilemma is not to follow most of the rest of the world by moving to a proper territorial tax system, in which profits are taxed only in the country where they are earned, but to impose a minimum global tax on U.S.-headquartered companies whether or not they repatriate their profits. If it could be enforced effectively, which is doubtful, the only consequence would be to encourage more companies to place their headquarters somewhere other than the United States.

What this proposal primarily does is to highlight the difficulty of trying to move discretely on any single aspect of tax reform. A tax system that is both more competitive and more fiscally responsible would require an array of changes. There are many ways reform could be sliced (which is why it’s so hard to do). My preference would be for significantly lower corporate tax rate to encourage investment, coupled with a Value Added Tax to raise revenue, discourage consumption, and boost exports, and a more progressive income tax system to offset the regressive VAT. Yet in the current political environment, two out of the three are deemed topics not worthy of serious debate.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store