Abacha, Abiola, and Nigeria’s 1999 Transition to Civilian Rule

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- John CampbellRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

- Jack McCaslinResearch Associate, Africa Policy

The 1999 transition of Nigeria from military to civilian, democratic government, is a defining moment in Nigerian history, representing the beginning of the longest, uninterrupted government since independence in 1960. But what exactly transpired during the period of transition, which began in earnest with the death of military dictator Sani Abacha in 1998, is not entirely clear. Max Siollun, in a fascinating study of the period, Nigeria’s Soldiers of Fortune, has done us a service by illuminating some of the behind-the-scenes machinations of that period, and putting to bed some of the rumors that passed for history.

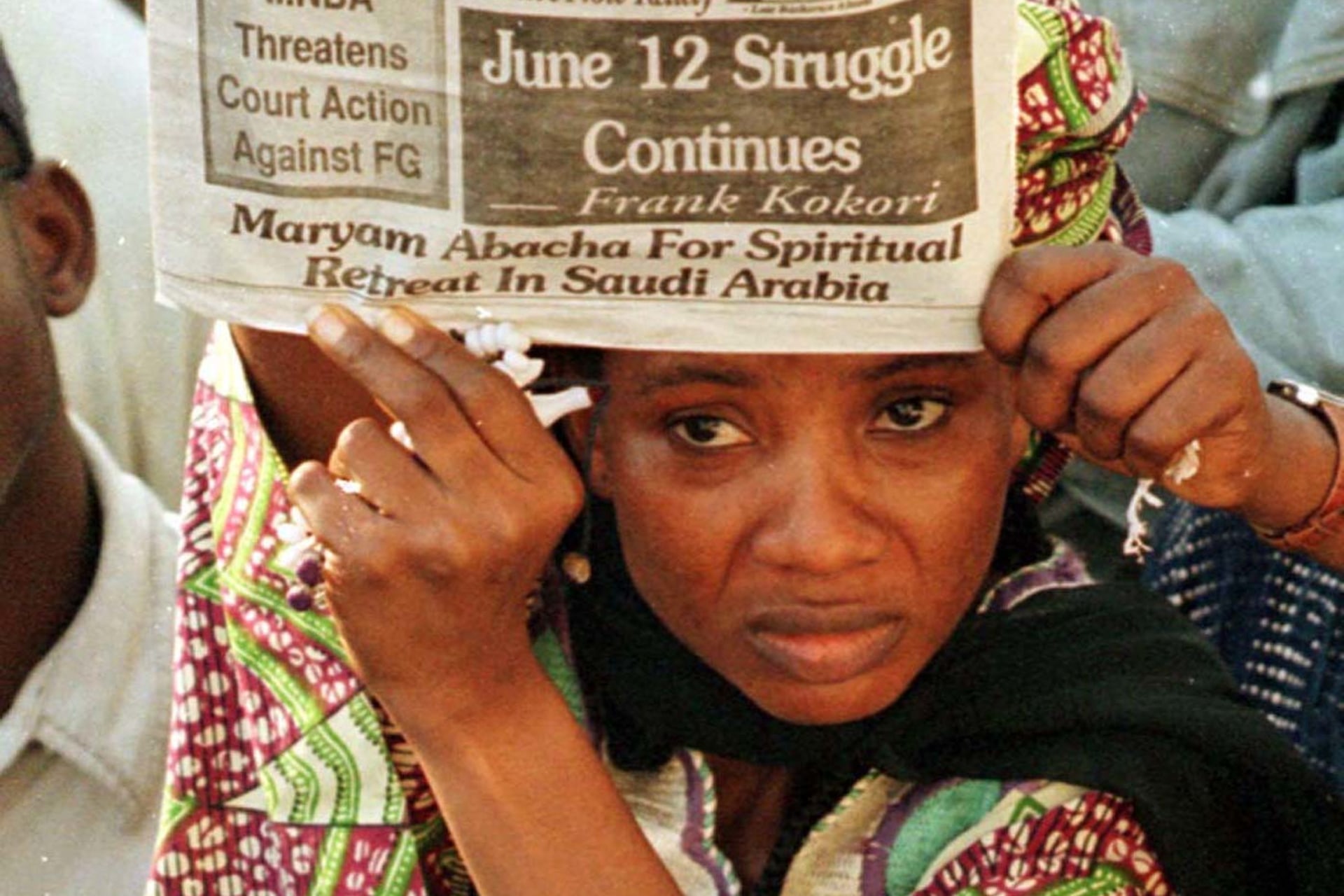

Abacha’s rule was unusually brutal for Nigeria, and unrest was spreading. Following his death, the cabal of military leaders and businessmen who ran the country concluded that civilian government should be restored, though the privileges of the military must remained intact. Moshood Abiola, a Yoruba from the southwest, had won the most recent presidential election in 1993, and at first glance would have seemed to be the most likely choice for the next civilian president. But, he was unacceptable to the military for reasons that still remain obscure. Abacha, after all, had jailed him on trumped-up charges and seized power following his election; the Muslim north was associated with the military and Abacha, who was a northern Muslim. Championed by the Yoruba establishment but unacceptable to the northern establishment, Abiola represented a roadblock to a transition. But, just as he was about to be released from government custody in 1998, Abiola died suddenly and in the presence of a small but high-level U.S. delegation that was taking tea with him.

Their deaths, in effect, cleared the way for democracy. With Abacha gone, the elite cabal could move to restore civilian government, and with Abiola gone, the military and the north would be placated and acquiesce to the transition. The deal that the cabal brokered led to the election of the Yoruba Olusegun Obasanjo as president, returned the military to the barracks while keeping open opportunities for them to profit personally in the new system, and established the regime of power alternation by which the presidency rotated every eight years between the south and the north, called “zoning” or “power shift.” This final convention was particularly important for the north, who had dominated military government and were fearful of a southern-dominated civilian government.

Hence, the deaths of Abacha and Abiola were convenient, perhaps too convenient, and so the rumor mill operated overtime. It was frequently said that Abacha died of poison injected into apples with which Indian prostitutes teased him. Abacha was a notorious womanizer with reports of strange goings-on at the chief of state’s residence in common circulation. As for Abiola, rumor abounded that the military poisoned him to prevent his release. (His food taster was off duty.) He, too, was a notorious womanizer, but by the time of his death, he had been in jail for years

Max Siollun, in his book, has carefully investigated the death of Abacha and Abiola. Systematically examining the evidence, he credibly concludes that both Abacha and Abiola died of heart disease, in Abiola’s case exacerbated by the bad conditions in which he was imprisoned. So the poisoned apples and the Indian prostitutes have been consigned to legend, as has Abiola’s absent food taster. In Nigeria, as everywhere else, convenient coincidences sometimes happen.