Did Greenspan suggest that the Fed no longer completely controls US monetary policy?

One of the most intriguing passages in the magisterial Ip/Hilsenrath account of the origins of easy credit in Tuesday’s soon-to-be Murdoch Journal comes when Ip and Hilsenrath quote Alan Greenspan discussing how long-term rates stayed far lower than the Fed expected once the Fed started to raise short-term rates:

Looking back, he [Alan Greenspan] says today: “We tried in 2004 to move long-term rates higher in order to get mortgage interest rates up and take some of the fizz out of the housing market. But we failed.” Something besides Fed policy was at work. Both Mr. Greenspan and his successor, Ben Bernanke, point to an unanticipated surge in capital pouring into the U.S. from overseas. Emphasis added.

That seems -- at least to me -- to be a rather remarkable admission. After all, the Fed controls at least short-term US interest rates, the expected path of short-term rates should have an impact on long-term rates and the housing market is rather interest rate sensitive.

We are only now -- after the most recent Treasury survey and the subsequent revisions to the BEA’s data on official purchases of Treasuries and Agency bonds getting a real sense of just how big a role foreign central banks played in that “anticipated surge in capital” from abroad.

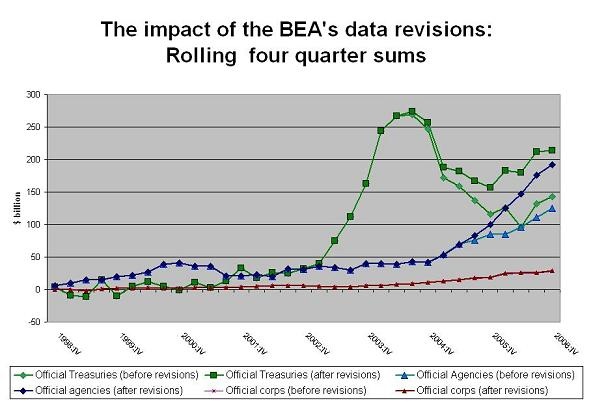

Consider the following graph. It shows foreign central bank purchases of Treasuries and Agencies before the recent data revisions (in light green for Treasuries and light blue for Agencies) and after the recent data revisions (dark green for Treasuries and dark blue for Agencies). Central banks were clearly big buyers.

Indeed, by the end of 2006, combined total official demand for Treasuries (over $200b over the preceding four quarters) and Agencies (a bit under $200b) was far higher than back in 2004. And some analysis suggests that central bank buying in 2004 had a rather substantial impact on US rates.

Moreover, the BEA’s revised data likely understates official inflows somewhat. The data from mid 2006 on likely will be adjusted upward when the next survey comes out. And the US data (reasonably) counts as private funds sovereign wealth funds and central banks hand over to external managers. And then there are inflows that are only indirectly financed by cental banks: a lot of the dollars central banks have deposited in European banks are lent out to European (and other) investors who want to buy US securities without taking the exchange rate risk.

Ip and Hilsenrath frame the debate over foreign inflows in terms of Bernanke’s global savings glut. But Bernanke’s formulation sets aside what to me is a key question -- did the savings glut emerge because the rest of the world just wanted to save more (or invest less), or is it a reflection of the policies adopted by other governments?

Brad DeLong makes a similar argument. He argues that Ip and Hilsenrath downplay the magnitude of official inflows and that they ignored that the world’s spare savings stem as much from a shortage of investment as a surge in savings.

I agree with DeLong’s first point, but not fully with his second point [Note: edited -- I initially left out a “not”]. The “investment death” argument worked better in 2004 than in 2005 or in 2006. That is when China’s current account surplus started to really surge, as savings grew even faster than investment. And that is also when the surge in oil and commodity prices led to a surge in government savings in the oil exporters, as commodity revenue grew far faster than domestic spending and investment. The increase in Chinese, Indian and oil savings seems more relevant than ongoing weak investment in southeast Asia (Thailand and Malaysia most notably).

I consequently do believe that there was something of a savings glut. But I also think that savings glut stemmed in large part from government policy choices -- not a surge in private savings.

The role goverment policy played in pushing up savings rates is fairly obvious in the oil exporting economies. The governments of most oil exporting economies get -- in the first instance -- most of the revenue from the country’s oil exporters. They either own the national oil company and thus get its profits or collective massive taxes and royalities on all oil exports. And at least initially, most of the oil exporting economies decided to save rather than spend the oil windfall. They stashed huge sums abroad -- with the central bank, with a transparent oil investment fund or in a secretive oil investment fund.

No matter. The dollars the oil exporters put on deposit in Europe -- or handed over to European fund managers to invest -- had to be put to work. And a lot were onlent to the US.

The role government policy played in increasing Chinese savings isn’t quite as obvious, but there is, at least in my view, a tight link. I have long found Martin Wolf’s argument that China’s government had to take a series of policy steps -- restricting bank lending, running a relatively restrictive fiscal policy, allowing the SOEs to hold on to their rising profits rather than pay dividends -- that pushed up China’s savings rate if it wanted to avoid a burst of inflation that would undo the RMB’s nominal depreciation to be rather persuasive. In this interpretation, the recent surge in China’s savings rate stems directly from its exchange rate policy --

The result: large current account surpluses, with savings growing even faster than investment in China and the oil exporting economies, huge central bank and oil fund purchases of US securities, and far lower long-term interest rates than the Fed expected.

This of course doesn’t mean that the Fed is powerless. It still exercises a lot more control over US monetary conditions than say China’s central bank. But if China’s central bank is buying lots of long-term bonds, it also implies that the Fed may have to push short-term rates up by more than it otherwise would in order to slow interest-rate and credit sensitive parts of the economy.

Update: The Economist on the growing importance of emerging economy central banks.