Governing the Next Technological Revolution

With the perils of heedless innovation all too apparent, and with a new and potentially more transformative wave of technical advances in the pipeline, global movements to govern the next technological revolution are beginning to take shape.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for the Internationalist

The following is a guest post by Kyle L. Evanoff, research associate in international economics and U.S. foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations.

The information superhighway of yesteryear has in many ways become the information battlefield of today. As veteran analyst P.W. Singer and debut coauthor Emerson T. Brooking detail in their timely new book, LikeWar, the internet’s origin as a military communications network foreshadowed its maturation into a warfighting domain. The story of cyberwarfare is well documented. But other dangerous trends—not least of which is the weaponization of social media—have also taken hold, underscoring the imperfect correlation between technological and human progress. Now, with the perils of heedless innovation all too apparent, and with a new and potentially more transformative wave of technical advances in the pipeline, global movements to govern the next technological revolution are beginning to take shape.

The unvarnished idealism that marked the early days of the internet has subsided in recent years. Digital technologies proved, as promised, to be handmaidens of globalization. In fewer than three decades, an estimated 4 billion individuals have come online, with the figure projected to rise to 4.6 billion by 2021. A smaller and more interconnected world, however, has not guaranteed closeness. Countries like China and North Korea have sought to build walls in cyberspace and balkanize the internet while others—Russia in particular—have made digital interloping into a form of statecraft. Meanwhile, extremist groups such as the self-proclaimed Islamic State have used the worldwide web to extend the efficacy and reach of their terror campaigns. Global interconnectivity, then, has often given rise to global tumult.

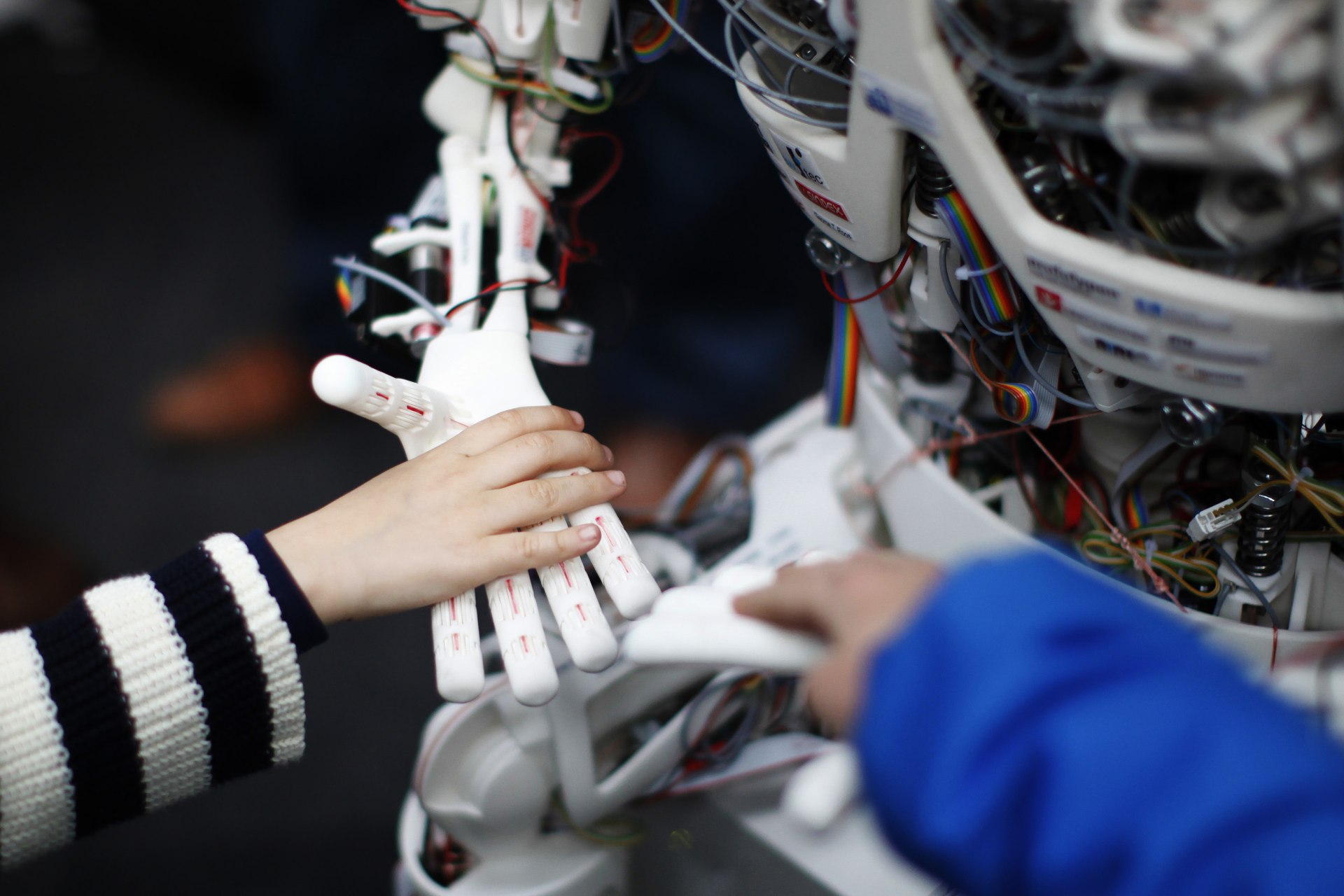

Today’s emerging technologies augur similar upheaval. Rapid innovation across numerous fields—artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, quantum computing, and nanotechnology, to name just a handful—continues apace, in what the World Economic Forum calls the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Like past industrial revolutions, which saw the advent and widespread adoption of outsized numbers of world-beating technologies, this revolution seems poised to bring incredible benefits and tremendous risks. Advances in artificial intelligence, for example, one field among many, could by various accounts enable vast increases in productivity, unlock new scientific discoveries, and accelerate progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals—or reinforce authoritarianism, amplify disinformation campaigns, and usher in new international arms races. These outcomes are not mutually exclusive.

Little wonder that Richard Danzig, a former U.S. secretary of the navy, has termed the current wave of innovation the “technology tsunami.” Even as the nations of the world are still coming to grips with the implications of digitization and globalization—with debates over data privacy and usage, market openness, and the limits of sovereignty, among others, remaining unsettled—this new deluge looms large. Global interdependence ensures that its consequences, economic and otherwise, will spill across national borders. At the same time, the limitations of the multilateral architecture are well known. A cracking world order, in which the President of the United States has become the laughingstock of the UN General Assembly, only compounds the difficulties of taking collective action. Just as many technologies are moving forward at exponential rates, the means to manage them are often stalling or throttling into reverse.

The same digital technologies that have so often fomented strife, however, have also opened new avenues for cooperation. In many instances, intergovernmental organizations and civil society groups are now using the internet to orchestrate transnational movements. Returning to the example of artificial intelligence, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)—a UN standard-setting body whose members include both states and private companies—has partnered with the XPRIZE Foundation and the Association for Computing Machinery to hold two AI for Good Global Summits. Following the first of these summits, held last year, the ITU introduced an online database to track initiatives related to AI and connect likeminded stakeholders in applying emerging technologies toward the Sustainable Development Goals. This AI Repository builds on decades of previous work on digital governance, linking projects to earlier international efforts to use information and communications technologies to further economic development. AI for Good, meanwhile, has become a rallying cry for proponents of AI and international cooperation.

Even as actors with divisive aims are weaponizing the digital tools of the previous technological revolution, the good Samaritans of world order are harnessing the internet and social media to prepare for the next technological revolution. In July, UN Secretary-General António Guterres established a High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation, giving it a broad mandate to explore possibilities for bridging the divide between rapid technological progress and lethargic political action. The panel will use online platforms to collect public input from across the globe, exemplifying how international bodies are using the internet to democratize political processes and inform decision-making. Multilateral institutions, of course, are not the only groups using the internet to give voice to the masses. In 2016, the Global Challenges Foundation, a Swedish philanthropy, poured $5 million worth of prize money into an online competition to crowdsource proposals for reshaping international cooperation to meet the needs of the twenty-first century. Now, with the contest over and the winners announced, the philanthropy is building grassroots support for global governance by sponsoring do-it-yourself hackathons, in which participants brainstorm ideas for addressing the world’s greatest challenges.

Rising to meet such challenges, however, will require using technology to do more than just build movements and bring new stakeholders to the table. Many of the most promising entries in the Global Challenges Foundation’s 2016 prize competition, now perusable in an online library, involve leveraging emerging technologies to improve global governance. Artificial intelligence and blockchain, potential digital mainstays of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, make numerous appearances, with automated and decentralized systems lowering the costs of governance and introducing entirely new modes of decision-making. While the prospects of success for any particular arrangement are a matter of speculation, the imperative to apply new technologies in governing is clear. International institutions must deepen their reservoirs of technical expertise and incorporate these innovations into their organizational structures and programmatic agendas.

The next global technological revolution is poised to bring tremendous upheaval. But many of the innovations that comprise that revolution will also be useful as tools for managing it. Just as social media can be instrumentalized in service of either discord or unity, so too will the technologies of tomorrow be useful as both swords and shields. As conflict in the digital realm has shown, dulling the sharp edges of technological innovation must be a global priority. Information warfare, for all its destructive capacity, is not likely to undo the deep globalization of today. Interconnectedness of one sort or another, with interdependence as a corollary, is almost sure to remain a persistent global feature going forward. Whether that interconnectedness proves more beneficial or harmful will hinge on the successes or failures of international cooperation.