How China and Russia Have Helped Foment Coups and the Growing Militarization of Politics

Militaries have become more involved in the governance and politics of nations worldwide in the last decade.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

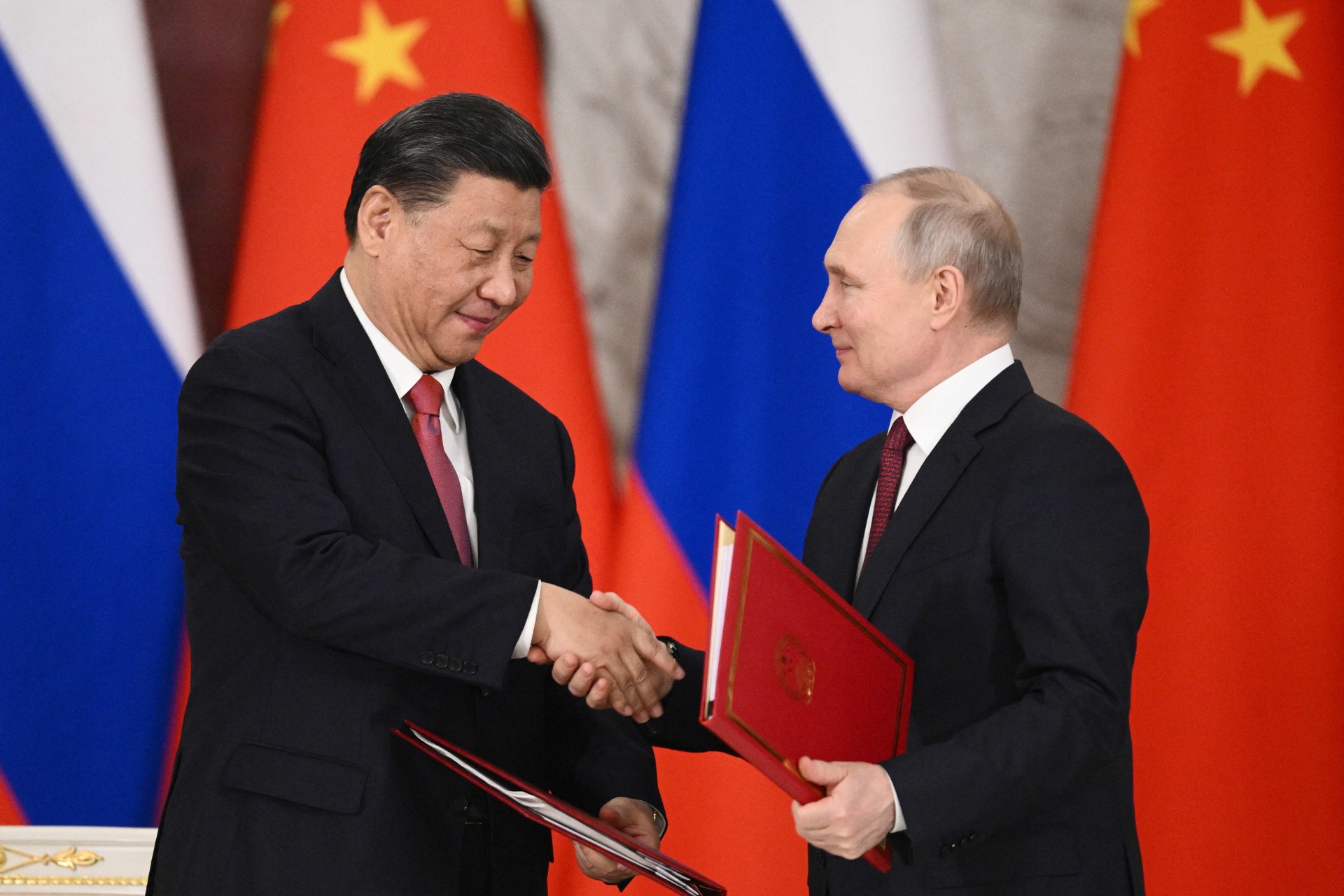

In the past decade, militaries worldwide have become involved in domestic politics and public policy formulation at levels not seen since the Cold War. There are multiple reasons for this trend, but China and Russia have played a critical role in fomenting, enabling, and accelerating coups and other revivals of military power. China and Russia have enabled militaries to launch and sustain coups or have helped militaries become involved in domestic politics in other ways.

This global trend has a range of significant policy implications: for publics in affected countries, including their democracies, rights, political parties, and governance; for the broader future of the global balance between democracy and authoritarianism, as China in particular pushes for an alternative, authoritarian world order and control of more strategic assets and minerals that could be critical in a U.S.-China armed conflict; for U.S. policymakers and other democratic powers dealing with the influence of the major autocrats in important regions; and, for policymakers attempting to navigate the changing global order and prepare for a possible growing conflict with China.

Militaries have increasingly returned to take power directly over the past decade. As the U.S. Institute for Peace noted, “the number of coups and coup attempts in 2021 matched the high point for the twenty-first century,” this high annual level of coups has persisted in the years since. In the past decade in Asia, there have been coups in Myanmar and Thailand. In recent decades, coups and attempted coups have occurred in Austria, Ecuador, Egypt, Fiji, Honduras, Moldova, Montenegro, Turkey, and many African states, most recently Niger and Gabon.

In a second set of circumstances, democratically elected leaders (though often with authoritarian tendencies) have invited militaries to play more prominent roles in electoral politics to bolster these politicians’ power, including over their political parties, in Brazil, Cambodia, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Venezuela. For instance, in Indonesia, the political leadership has involved the military in campaigning during elections, as was the case in Brazil, Myanmar (before the coup), Nigeria, the Philippines, and other states. Elected leaders also are increasingly handing armed forces greater governing and policymaking responsibilities. Those leaders, from Bangladesh to Brazil, from Ecuador to Indonesia to Mexico to the Philippines, employ militaries as domestic police forces, election observers, economic planners, heads of major companies, and even judges. In all those positions, militaries face fewer constraints than actual police, judges, or other bureaucrats.

This remilitarization has domestic and international causes. In many countries where militaries have gained outright control again or are at least wielding significant power, populations have soured on nearly all institutions except for the armed forces. Indeed, the return of the men in green to politics comes amidst over fifteen years of global democratic regression. It comes at a time when public opinion across a broad range of countries has become more willing to consider authoritarian politics. Another important reason is the desire of democratic but populist leaders, such as Indonesian President Joko Widodo, for a source—the armed forces—that can increase the leaders’ power, nationally and within their parties, without checks and balances.

Yet geopolitical competition and a desire to create an alternative and autocratic global order to the existing one is a major, understudied cause and accelerant in this remilitarization. China and Russia are either directly promoting militaries’ returns or helping them consolidate their influence once armed forces have already gained greater power—in other words, pouring fuel on the fire of remilitarization and, in China’s case, definitively trying to create an alternative world order to that led by the United States. Moscow had not been a player in Africa for decades after the Cold War. Still, via the Wagner mercenary group and regular Russian soldiers, it has recently involved itself deeply in a range of African states. According to the Brookings Institution, “between 2015 and 2019, Moscow signed nineteen military collaboration agreements with African governments.” The Tony Blair Institute notes that “Russia has deployed private military contractors [usually to bolster local militaries] in at least twenty-one countries since 2014, with the majority on the African continent.” Russia has been a direct cause of military takeovers in Africa, using the Wagner Group to help military dictators take or hold control of countries like Libya and Mali, as well as the Central African Republic, where an elected leader has now become a military-backed dictator supported by Russia. Vladimir Putin’s government has also tried to foment coups in Montenegro and Moldova to destabilize Eastern Europe.

Putin’s regime has also been opportunistic and acted as an accelerant when militaries gain domestic power. Russia has built its presence in Burkina Faso, Chad, Congo, and Guinea, among others. It is now proposing to play a role in Niger and possibly Gabon, accelerating military power there. Some Russian experts speculate that Moscow also is working to ingratiate itself with other Sahelian militaries. (Despite Wagner’s apparent demise in Russia after its rebellion, Wagner is still playing a role within Africa, and it also appears that regular Russian military forces will step into some places where Wagner played a significant role in Africa.)

China, meanwhile, has directly supported coups or acted as an accelerant for military regimes in a less direct but, in many respects, dangerous way than Russia/Wagner’s outright backing for coups. Instead, China seems to sanction coups and then use many tools to cement and justify the military takeovers. China (and sometimes Russia) uses its power at the United Nations to block resolutions condemning military regimes or taking any UN action against them. Many experts believe that China knew a coup was coming in Myanmar in early 2021 and sanctioned the takeover and that it likely knew a coup was also about to occur in Thailand in 2014. It then immediately used aid, rhetorical support, arms, trade, and other measures to show its backing for coup governments in Myanmar and Thailand, as well as in places like Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Sudan.

In addition, Russia, and particularly China, seeking to create an alternative, authoritarian global order to that of the U.S.-led current order, have played a significant role in supporting many, but not all, of the elected leaders who are bringing the military back into politics. For instance, Beijing has bolstered rhetorical, financial, and military support for states, from Cambodia to Indonesia to the Philippines to Sri Lanka, where the military was handed greater power within political systems, such as by supporting Joko Widodo’s move to give more power to the military, and backing his decision with greater aid and assistance.

Russia has taken similar tactics—it also has bolstered its aid, rhetorical support, and other types of support for such governments, from Indonesia to Nigeria to the Philippines to Thailand, where leaders hand more power to militaries. (There are examples, like Brazil, where this type of support for elected leaders trying to give power to armies did not succeed.) Indeed, overall, China and Russia have become far more assertive in openly stating their attempts to aid other authoritarian regimes, and particularly military regimes, as part of a desire to support authoritarianism openly and to create an alternative world order to that of the U.S.-led West, and strategic assets that will help them maintain that order and prepare for conflict, a major goal of Xi Jinping and, to some extent, Vladimir Putin.