How the U.S. and EU Could Harmonize Their Approaches to Trade in EVs and Steel

Both the U.S. and the EU want to avoid relying too heavily on China’s enormous capacity to produce steel, and neither block is interested in ceding electric vehicle manufacturing and the battery supply chain to China.

However, in each sector, the approach adopted by the two big blocks has differed.

More on:

In electric vehicles, the U.S. has relied on “Buy American” provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. There are separate requirements for qualifying for the battery subsidy and the subsidy for the vehicle itself. Plus, the U.S. has built a tariff wall that more or less blocks direct auto imports from China, thanks to the 25 percent tariffs from the big Section 301 case against China.

The EU is far more open. Its national EV subsidies aren't generally linked to “Buy European” requirements (though French President Macron thinks they should be, and France often flirts with measures that seek to achieve a measure of European preference without being explicit about it) and thus imported EVs from China generally qualify for European subsidies. To counter the surge in imported EVs, the EU is now considering a counter-subsidy investigation against Chinese EV production, which could eventually generate tariffs that are blessed by the WTO. The big advantage of a formal anti subsidies investigation, at least in theory, is that China cannot retaliate for subsidies that simply offset (countervail) the impact of domestic Chinese subsidies on its trading partners.

Steel is, of course, even more complex. Both the U.S. and the EU have extensive bilateral tariffs on Chinese steel (dumping duties and counter-subsidy duties). But both economic blocks have introduced broader, global measures that put tariffs on imports from countries other than China. The U.S. famously introduced unilateral Section 232 (National Security) tariffs, which the WTO hasn’t exactly blessed (ask Ambassador Tai). The EU has introduced safeguards to protect its steel sector from the distortions created by the U.S. national security tariffs. That's right, the EU safeguards are technically a response to the U.S. tariffs, not China's immense investment in steel capacity. The EU is also planning a new anti-subsidy case against China.

More importantly, the EU is heading toward a tariff (or a charge) on the carbon content of imported steel, through the soon-to-be implemented Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The EU's carbon adjustment, in principle, ensures that imports face the same charges at the border that European producers face when they need to buy their emission permits.

The net result of these differing measures has been ongoing friction despite a common desire to limit the impact of the distortions created by Chinese subsidies on their home markets in key goods.

More on:

Europeans are frustrated that European batteries and cars don’t qualify for U.S. consumer EV subsidies in a straightforward way (though the “leased vehicle” exception provides ample ground for trade), as well as the persistence of national security tariffs that apply to close security allies. Americans are frustrated by the contortions created by the EU’s desire to respond to China's distortions by only using measures that fit within the narrow confines clearly allowed by the WTO (The U.S. also takes a more expansive view than the EU about what the WTO allows).

These competing approaches to managing the Chinese threat have led to the fracturing of the transatlantic markets for not only clean energy goods, but also dirty goods like steel that need to become clean to lower global carbon emissions.

Is there an alternative, given that the U.S. isn’t likely to ground its response in the four corners of what the WTO clearly allows, and that the EU generally wants to avoid following the U.S. into WTO purgatory?

Perhaps – though it does require compromises on both sides to produce measures that are more consistent across the Atlantic. That includes a greater willingness by the EU to make use of all of the flexibility allowed by the WTO, and operate in what some would consider a legal grey zone.

On electric vehicles, the EU’s desire to respond within the WTO “rules” actually means that its policy response to China doesn't match China’s own measures. Countervailing duties (CVDs) would be WTO consistent, but not reciprocal.

China, after all, not only has domestic production subsidies (often provided at the provincial level) for its EV manufacturers, but also a very strong – even if informal – set of “Buy China” policies that blocked imported vehicles from qualifying for its consumer subsidies lists. Jacky Wong reported in the WSJ:

“Getting on the [certified EV battery manufacturers] list when it was introduced in 2015 qualified battery makers for government subsidies that account for a significant chunk of the price of an EV. No big foreign players made the grade.”

Korean companies producing batteries in China (to take advantage of China's extensive and subsidized supply chain in critical battery materials) initially could supply foreign markets from China, not supply the domestic Chinese market. As Issues in Science and Technology noted:

“The central government, as well as provincial and city governments, made subsidies available only to companies assembling vehicles in China ... Chinese automakers [also] had to use an approved Chinese supplier of LIBs to qualify for PEV subsidies. Japanese and Korean battery producers, even though they were investing in Chinese facilities, were effectively excluded from the Chinese market for several years.”

China liberalized this rule in 2019, but only after CATL and BYD had reached scale, helped by subsidies of their own.

And there were separate requirements for the vehicle itself. Fair enough, someone has to determine what is or isn’t an electric vehicle. But no imported vehicle has ever made the list and thus qualified for the subsidy. Foreign companies like Tesla that produced in China with a Chinese made battery did eventually qualify, but only by producing in China. Imports, of course, also face China's own substantial auto tariff (15 percent applied, 25 percent bound).

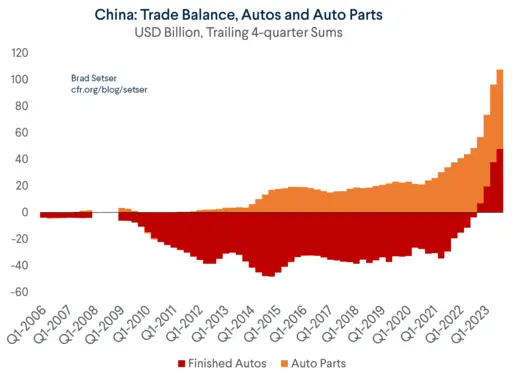

China's industrial policy here, while clearly discriminatory, was effective. Chinese production of EVs, nurtured behind a protective wall, gained scale, and now Chinese EV production dominates the global market (see Keith Bradsher, Greg Ip, and many others). Indeed, EV production, plus the spare capacity inside China for the production of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, have turned China into a massive global exporter of EVs in next to no time.

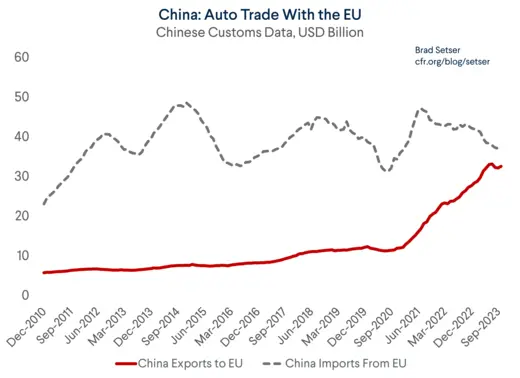

Europe is also struggling to adapt to a world in which China is a net exporter of autos and auto parts, not a net importer – and thus a direct competition to one of Europe's most important and strategic industries.

The symmetric response to Chinese EV policies by the EU would be to introduce “Buy European” requires for the EV subsidies offered by EU member states. Such policies would also have the advantage of encouraging European firms (and Tesla) to invest in European capacity to meet European EV demand, and not use their Chinese factories to supply European demand (and get the European subsidies). It is unclear whether the CVD cases will target European firms producing in China (and Tesla, which almost certainly benefitted from Shanghai subsidies).

“Buy European” policies aren’t clearly allowed by the WTO – though there might be a complex case that they could be allowed as an offset against discriminatory Chinese policies. The basic WTO principle is that consumer subsidies should be equally available to producers operating in all the WTO’s member countries.

But if European countries were willing to run a bit of WTO risk (China would have to complain about other countries adopting its own policies, but, hey, anything is possible), the introduction of “Buy European” policies could also lay the basis increased cooperation with the United States. Think of a “subsidy-sharing” agreement where U.S. made cars qualified for European subsidies and European made cars qualified for U.S. subsidies. The resulting agreement would create open and integrated transatlantic market between the U.S. and the EU – and ultimately among the U.S., Canada, Mexico, the UK, and the EU. Call it a North Atlantic Electric Vehicle Community.*

The U.S. would need to amend the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to give European producers access to all vehicle and battery subsidies in the IRA (assuming European content requirements were met), so this would take an act of Congress. It is more effective than the battery subsidy-sharing that would result from a critical minerals trade agreement.

The result would be a modest reduction in the EU’s WTO purity, but also much deeper integration between the U.S. and the EU, with all the gains that could come from more open trade between the two largest market economies. And, well, the EU would be responding totally symmetrically to China's own policies. China, remember, never let European-made EVs qualify for its own subsidies.**

What of steel?

Well, the U.S. should be the one doing the innovating here.

The existing 232 tariff is assessed on the basis of the value of imported steel – with a 25 percent ad valorem tariff (import price plus 25 percent) on all imports. Well, technically on a portion of all imports, as a lot of imports come in under various exclusions, as well as the tariff-rate quotas negotiated with the EU and other key trading partners.

But there is nothing in the underlying 232 statute that requires ad valorem tariffs in response to a national security finding – that is just a policy choice.*** The 232 process concluded that imports back in 2017 were displacing domestic production in a way that threatened the ability of the U.S. to meet national security needs, but left open the choice of tool to meet the goal of assuring sufficient domestic U.S. production capacity.

The U.S. thus in theory could move from assessing a tariff on the value of imported steel to assessing a tariff on the carbon content of imported steel. So long as the tariff on the carbon content assured the production of sufficient domestic steel to meet U.S. national security needs, my guess is that it would meet the requirements of the law.

And well, a tariff levied per ton of embedded carbon on imported steel would look a lot like the EU’s CBAM (“The price of the CBAM certificates will be calculated depending on the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances expressed in €/tonne of CO2 emitted”). And if the U.S. carbon tariff happened to be set at the same per ton level as the EU’s CBAM, European steel would sell at the same price in the U.S. as in Europe.

The U.S. could then drop all the other current restrictions on steel trade – apart from the standard trade remedies (dumping duties and CVDs) that have long been in place. Make things simple. Chinese steel – and the steel produced by Vietnam, Indonesia, and India for that matter -- is quite carbon intensive, so it would face a substantial penalty.

The result would be relatively open and harmonized trade in steel (and aluminum) across the Atlantic. The EU's future green steel production would enter the U.S. essentially tariff-free. European producers have a leg up here; it wouldn't be a bad thing if American producers faced a bit of pressure to raise their own game.

There obviously is a catch – the U.S. would be imposing a tariff on high-carbon steel imports, but not taxing the domestic production of high-carbon steel. That isn’t totally WTO-consistent. Then again, it isn’t totally WTO-inconsistent either, as the measure would serve the broader purpose of securing a sufficient domestic supply of steel to meet U.S. national security needs. The U.S. position is that the WTO should basically allow countries to assess for themselves what is needed for national security and thus what qualifies for the WTO's national security exemption. The U.S. would be operating under the same WTO exception it now uses.

And even if the EU wouldn’t be totally happy in a world where the U.S. had a carbon tariff without a carbon price, it would set the U.S. on a path that the EU should like – as it would lay the obvious groundwork for the eventual imposition of some form of carbon pricing for U.S. production (the U.S. does need to incentivize lower carbon production of primary steel for the automotive industry, which heavily overlaps with the high-quality steel needed in a lot of defense applications).

The basic idea here should be clear – harmonizing the tools used to limit trade in both EVs and steel to a circle of friends would allow deeper integration between historic allies while maintaining restrictions on China's access to either EV subsidies (though some Chinese EVs may be competitive without subsidies) or U.S. and EU steel demand.

And well, China has never really provided the U.S. or the EU with unfettered access to its own consumer subsidies or industrial markets in autos or steel, so it is a globally symmetric system is well.

It does, however, value integration over strict adherence to a narrow interpretation of the WTO’s rules. Rules which, at least from the U.S. point of view, suffer from requiring the U.S. to treat China just like everyone else. See Peter Harrell's Greenwald lecture at Georgetown.

With regards to steel, it is a rather different approach than the U.S. has put forward in the negotiations over a global arrangement for sustainable steel and aluminum (the “green steel club”). The U.S., to my knowledge, hasn't proposed dropping the current structure of the 232 steel tariffs and moving toward a tariff on the embedded carbon content of steel imports. Rather, the idea is more or less to give additional exclusions to clean steel imports from inside the club.**** Negotiations there have stalled, though, and there isn't currently any chance for a deep agreement; the U.S. and the EU will likely agree to extend the current truce beyond the U.S. election.

A more creative set of proposals might have a better chance of breaking the current impasse.

* Similar subsidy-sharing agreements could be reached with a broader set of countries, notably Japan and key U.S. allies in the Pacific.

** The EU’s efforts to avoid Chinese auto retaliation by sticking to WTO-consistent remedies are unlikely to succeed; China’s auto tariffs are currently below the maximum allowed by the WTO, so China has the unilateral right to raise tariffs on imports from the EU and others back to 25 percent. China has a long history of finding other ways to retaliate, as well. It would, in a sense, be harder for China to retaliate against buy European provisions, as it already effectively has strong “Buy Chinese” requirements on its EV subsidies in place. Europe is more vulnerable than the U.S. to Chinese retaliation because European firms still make luxury internal combustion engine sedans in Europe for sale in China, and thus trade isn't one-sided.

*** Conclusion of the 232 investigation: “The displacement of domestic steel by imports has the serious effect of placing the United States at risk of being unable meet national security requirements. The Secretary has determined that the ‘displacement of domestic [steel] products by excessive imports’ of steel is having the ‘serious effect’ of causing the ‘weakening of our internal economy.’”

**** See the debate between David Kleimann and Todd Tucker and Tim Meyer on a “Green Steel Club.”

Online Store

Online Store