Kenya’s Silicon Savannah Spurs Tech in Sub-Saharan Africa

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for John Campbell

This is a guest post by Aubrey Hruby and Jake Bright. They are the authors of The Next Africa: An Emerging Continent Becomes a Global Powerhouse.

The role of technology in sub-Saharan Africa is growing. An emerging information technology (IT) ecosystem is reinforcing regional trends in business, investment, and modernization. There is a growing patchwork of entrepreneurs, startups, and innovation centers coalescing from country to country.

Most discussions of the origins of Africa’s tech movement circle back to Kenya, which was home to several major technological innovations between 2007 and 2010. This innovation inspired the country’s Silicon Savannah moniker, and has provided an example for other African countries to follow.

In 2007, Kenyan telecom company Safaricom launched its M-Pesa mobile money service to a market lacking retail banking infrastructure yet abundant in mobile phone users. The product converted even the most basic cell phones into roaming bank accounts and money-transfer devices. Within two years M-Pesa was gaining nearly six million customers and transferring billions annually. The mobile money service shaped the African continent’s most recognized example of technological leapfrogging: launching ordinary citizens without bank accounts into the digital economy.

Shortly after M-Pesa’s launch, four technologists created the Ushahidi crowdsourcing app in response to Kenya’s 2007 election violence. The software that evolved became a highly effective tool for digitally mapping demographic events anywhere in the world. Ushahidi has since become an international tech company with multiple applications in more than twenty countries.

In 2008, Erik Hersman, an Ushahidi co-founder, hatched Nairobi’s iHub innovation center after identifying the need for “[permanent information technology] community spaces…in major cities [for] young entrepreneurs. The nexus point for technologists, investors, [and] tech companies.” Since 2010, 152 tech companies have formed out of iHub. It has 16,000 members and on any day, numerous young Kenyans work in its labs and interact with global technologists. iHub gave rise to Africa’s innovation center movement, inspiring the upsurge in tech hubs across the continent.

Another Kenyan milestone was the government’s 2010 completion of The East African Marine System undersea fiber optic cable project, which increased East African broadband and led to establishment of a national Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Authority.

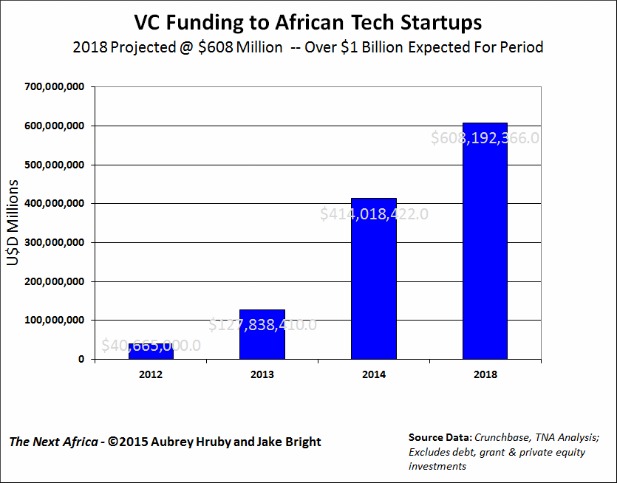

Today, Silicon Savannah is but one corner of sub-Saharan Africa’s tech scene. Across the region a Silicon Valley inspired network is developing. Nigeria is a hotbed for startup activity. Facebook recently announced an initiative to beam internet access to Africa from space. Silicon Valley investment is funneling into ventures from Kenya to South Africa. In total, our research highlights the existence of roughly two hundred African innovation hubs, 3,500 new tech related ventures, and $1bn in venture capital to a Pan-African movement of startup entrepreneurs.

Our study also reveals growing connections between the United States and sub-Saharan Africa’s IT sector. Tech giants IBM, Microsoft, and Google are expanding business operations in the region and partnering with African innovation centers. Repatriated entrepreneurs from the U.S. contemporary African diaspora are leading many of the continent’s tech incubators and startups.

All three of Africa’s most prominent ecommerce startups--Jumia, Konga, and MallforAfrica--were founded by Nigerians who earned their university degrees and initial private sector experience in the U.S. A noteworthy portion of the combined $300 million in venture capital to these entities comes from American investment firms, attracted to the opportunities of digital sales to the world’s fastest growing population expected to consist of 540 million smartphone owners by 2020.

Following the lead of countries such as South Africa and Kenya there are growing expectations on African governments to flesh out plans and infrastructure for information and communication technologies. Countries such as Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Ghana are already feeling the pressure, conscious of the success of Silicon Savannah. Most of SSA’s tech applications are emerging as solutions to local challenges, but this is creating unforeseen opportunities for other markets. Business people and investors are using IT in Africa to solve longstanding socio-economic issues formerly relegated to the development sector. Aid-agency grants previously going to NGOs are already being diverted to social-venture African tech organizations.

It is still early days for sub-Saharan Africa’s burgeoning IT sector. As it continues to connect with the region’s demographic and economic currents, expect tech to play an increasingly significant role in Africa’s business, politics, and international relations.