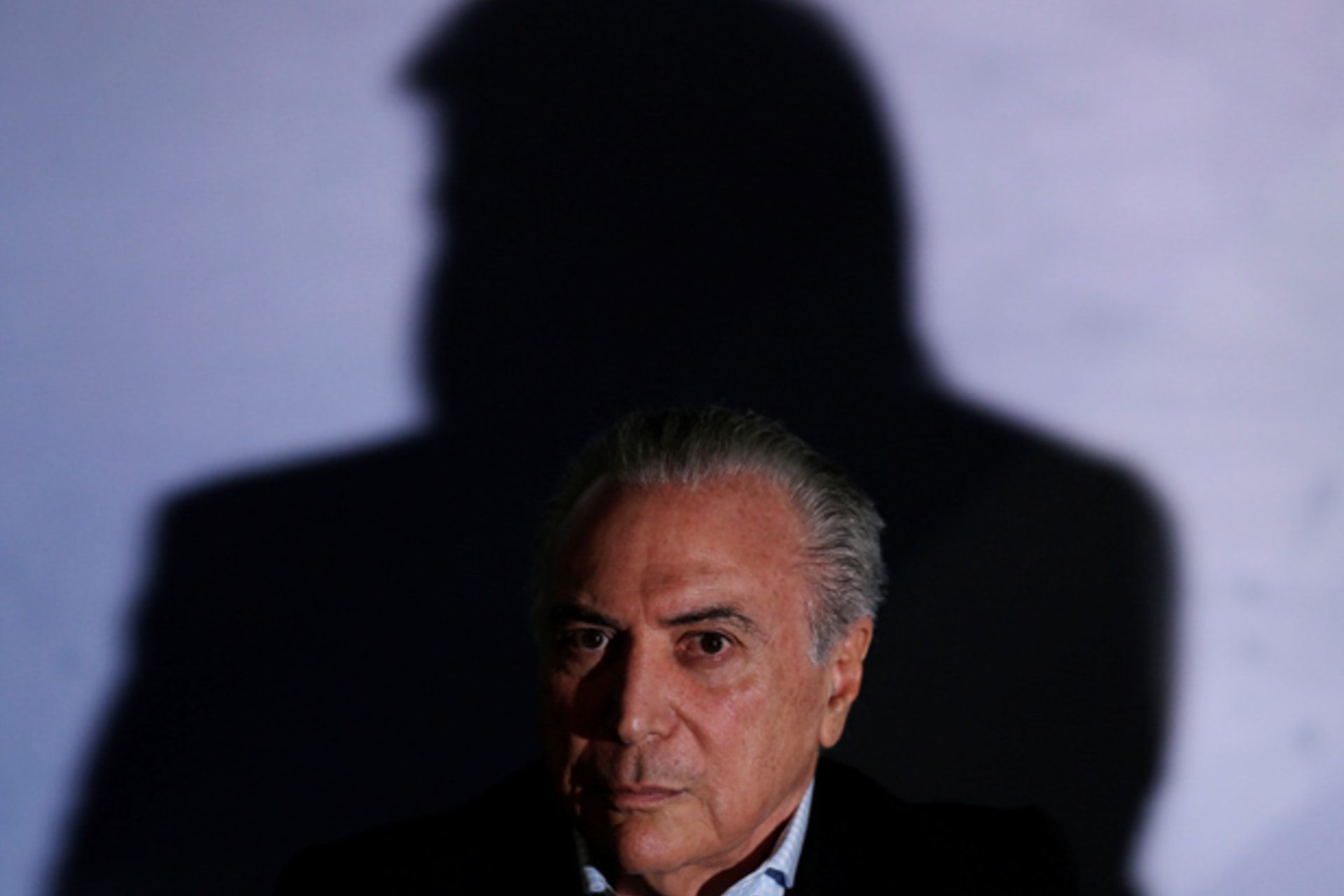

Michel Temer’s Shrinking Presidency

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Matthew M. TaylorAdjunct Senior Fellow for Latin America Studies

When he officially became president three months ago, Michel Temer’s game plan was simple and bold: in the roughly eighteen months before the 2018 presidential campaign ramped up, he would undertake a variety of legislative reforms that would put the government’s accounts back on track, enhance investor confidence, stimulate an economic recovery, and possibly set the stage for a center-right presidential bid (if not by Temer himself, at least by a close ally). Temer’s band of advisors—Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) stalwarts and long-time Brasília hands Romero Jucá, Geddel Vieira Lima, Eliseu Padilha, and Moreira Franco—would ensure that he had the backing of Congress to push through reforms that might not bring immediate returns, but nonetheless might improve investor confidence, prompting new investments in the short term. Sotto voce, many politicians also assumed that the PMDB—which has been an integral player in every government since the return to democracy in 1985—would be well placed to slow the pace of the bloodletting occasioned by the massive Lava Jato investigation and stabilize the political system.

This game plan appears to be running into a variety of self-inflicted troubles that will force the famously elastic Temer into difficult choices between his party and an angry public. Last week, the public’s worst suspicions of the PMDB-led government were confirmed in a two-bit scandal that claimed government secretary Geddel Vieira Lima. Vieira Lima fell on November 25 because of a petty effort to bring political pressure to bear on a historical registry office that had been holding up construction of a Salvador building in which he had purchased an apartment. More shocking, perhaps, was that the preternaturally cautious Temer helped Vieira Lima to exert pressure on the minister of culture whose office oversees the registry. The minister resigned, Vieira Lima fell, and Temer was left looking smaller than ever—a dangerous spot for a president whose legitimacy is already suspect.

Temer sought to repair the damage by holding an unusual press conference Sunday in which he promised to veto a proposed congressional amnesty of illegal campaign contributions. But Temer now faces another important ethical fork in the road: how to respond to the remarkable chutzpah of the Chamber of Deputies, which moved in the early morning hours of November 30 to neuter anticorruption reforms and prevent judicial “abuses,” a move widely seen as an effort to intimidate judges and prosecutors. The severely mangled anticorruption reform, bearing little semblance to the original draft, now heads to the Senate, which seems unlikely to repair the damage, and indeed, may further distort the bill in an effort to undermine Temer’s ability to resurrect the reforms through selective vetoes.

The reform package had been a poster child for the prosecutors that are spearheading the Lava Jato investigation, and it was pushed onto the legislative agenda in a petition drive that gathered more than two million signatures. Widespread grief over the Chapocoense tragedy may temporarily blunt public reaction to this bold late night maneuver, which was only possible because it had support from across the political spectrum, including the Workers’ Party (PT) of impeached president Dilma Rousseff, the clientelist Progressive Party (PP), and of course, members of the governing PMDB. But the public is fed up with politics as usual, and it does not take a leap of imagination to imagine that sporadically brewing public demonstrations might easily tip into a broad groundswell against the self-serving political class.

Meanwhile, Lava Jato continues to cast a long shadow, and the possibility that a deal may soon be signed between the Odebrecht construction firm and Brazilian, Swiss, and U.S. authorities has caused many a sleepless night in Congress. Press reports suggest that this may be the largest deal ever announced, surpassing even the US$1.6 billion in penalties that Siemens paid to U.S. and European authorities for worldwide corruption in 2008. The possibility that nearly eighty Odebrecht executives might sign individual plea bargains, and reports that as many as two hundred federal politicians may be implicated, suggests that the Congress could soon be paralyzed. Meanwhile, the PMDB’s motley crew has been decimated, undermining Temer’s ability to coordinate with Congress: Geddel Vieira Lima has resigned; Romero Jucá was driven out of the Planning Ministry soon after he was appointed in May (when wiretaps caught him discussing efforts to slow down Lava Jato); the high court this week is expected to take up a criminal case against Senate President Renan Calheiros (for allowing a construction firm to pay childcare to a mistress); impeachment impresario Eduardo Cunha is in jail; and Eliseu Padilha and Moreira Franco are frequently rumored to be next in the Lava Jato crosshairs.

Despite some initial success on fiscal reform, the appointment of solid and credible managers to key positions in state companies and ministries, and important regulatory changes intended to attract new investment, the outlook for the remainder of the Temer term remains grim. Economic forecasts now show economic growth of less than 1 percent in 2017. The budget situation of the twenty-six state governments is critical, and politically influential governors are begging for federal help. A much-needed pension reform promised by Temer has not yet been made public, much less begun the tortuous amendment process in Congress. Temer increasingly is being forced into a choice between helping his legislative allies and achieving economic reform, or satisfying a public that is baying for accountability and a political cleanup. It will take all of Temer’s considerable political skills and knowledge of backroom Brasília to revise his game plan for these challenging times.