More on:

There have been a few of reads on Nigeria that I wanted to call your attention to. Yesterday, Human Rights Watch, in a report, attributed 935 deaths to alleged attacks by Boko Haram since July 2009. (We have recorded 855 deaths since May 29, 2011 in our Nigeria Security Tracker but that includes deaths caused by security services in pursuit of Boko Haram.) Read it here.

I also published an oped in the International Herald Tribune today that explores the similarities and differences between Boko Haram and the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), and implications for possible Nigerian government responses. Read it here.

Finally, Nic Cheeseman, university lecturer in African politics and Hugh Price fellow of Jesus College at University of Oxford, on his blog “Democracy in Africa,” has published one of the most thought-provoking, convincing analysis I have seen of the Jonathan administration’s attempts to end the fuel subsidy by an anonymous author. Read it here.

In “Adding Fuel to the Fire in Nigeria,” the author makes the fundamental point that ending the fuel subsidy is not about economics – it is about the patronage politics that govern Nigeria—a point with which I wholeheartedly agree.

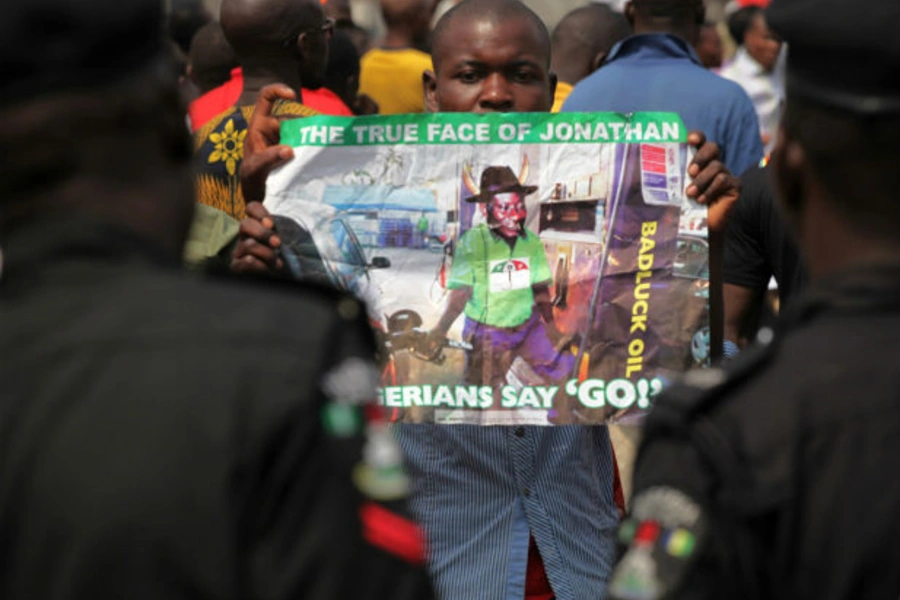

Fundamental to his argument is the observation that Goodluck Jonathan has two weaknesses: “legitimacy and cash.” Bluntly, he shows that by ending power alternation between Northern and Southern political elites, Jonathan must establish his legitimacy by providing them with kickbacks from government contracts. And that is expensive.

But, there is no money for big projects in the medium term that would generate the necessary contracts. So, Jonathan tried to eliminate the fuel subsidy, now almost a quarter of the federal budget. (He succeeded in getting rid of about half of it.) In a sense, he has thereby transferred his shortage of funds to the backs of the Nigerian people.

At the end of the day, he notes that it “does not matter” whether Jonathan is able to exercise meaningful presidential power. The central government has been in retreat. In the last months of the Yar’Adua administration, there was no government at all, and that hardly mattered. So, the Nigerian elites with their increasingly impotent government can hunker down in Abuja (which he brilliantly characterizes as a “national scale version” of the old Government Reserve Areas of colonial times) and continue indefinitely to live off the profits of oil and gas.

Anonymous concludes his insightful essay by raising the question of whether as the central government retreats, “which devolved, democratized or fissiparous forces are coming in to fill the vacuum that has been created by the retreat of the center.” The author seems to recall the success of protests across the country and raises the possibility of a shift in power towards the public.

While I agree that something new happened during these fuel subsidy protests, I also have two thoughts about the possibility of more radical change.

The military, especially the army, still has guns. While the upper reaches are co-opted by the administration, and are probably doing very well out of the ‘system,’ that is much less true of the rank and file and of junior and mid-level officers, whose families and friends feel the effects of the fuel subsidy cut as well as the country’s general decline.

Nigerian elites are terrified of the possibility of a junior officer coup. They ought to be. If one happens, it is likely to be bloody, because it might take the form of a mutiny against senior officers.

Another possibility is the much feared “Road to Kinshasa,” in which, according to John Paden, “societies were based on strife, with beleaguered dictatorships, minimum social control, the economics of isolation, and the tearing of the social fabric.” In conjunction with Boko Haram in the North, an ethnically divided and “ghettoized” Middle Belt, and a revival of the MEND insurrection in the Delta, the pressures might be too great for Nigeria’s current political economy to sustain, leading to an implosion in unpredictable ways.

Either of these possibilities would likely be a disaster for the Nigerian people. But, the strike and the demonstrations associated with ‘Occupy Nigeria’ did bring together Nigerians across religious and ethnic lines. That could happen again. Their solidarity – if only for a week – provides hope for the future.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store