The Nonaligned Movement’s Crisis

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Stewart M. PatrickJames H. Binger Senior Fellow in Global Governance and Director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program

Like the West, the developing world is struggling to update global institutions to twenty-first century realities. The Nonaligned Movement (NAM), which holds its sixteenth summit in Tehran this week, is grasping for contemporary relevance. It is clinging to shopworn shibboleths and cleaving to outdated bloc mentalities within the United Nations and other global bodies. In so doing, the NAM is undermining the search for constructive solutions to today’s most pressing transnational problems.

The NAM dates from the early Cold War, when many nations, particularly newly independent states, were determined to avoid choosing between Moscow and Washington. Its early leaders—Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Gamel Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Josef Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, Kwame Nkumrah of Ghana, and Sukarno of Indonesia—were giants of the era. In 1955, Sukarno hosted a landmark Afro-Asian conference in Bandung, Indonesia—the first summit not dominated by major powers. The conferees pledged to uphold the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all nations, embraced the equality of all nations and races, championed national liberation movements against colonial powers, and insisted on non-aggression and non-interference in international relations.

What began to emerge in Bandung was a distinctive, “Southern” vision of world order, in which the developing world would offer an independent center of gravity apart from the crumbling European empires and the colliding superpowers. Not all observers approved. The doctrine of non-alignment “pretends that a nation can best gain safety for itself by being indifferent to the fate of others,” U.S. secretary of state John Foster Dulles railed in 1956. “It is an immoral and short-sighted conception.”

The NAM really took shape in 1961, when Tito hosted the first “Conference of the Heads of State or Government of the Non-Aligned Countries.” For that first decade, the NAM’s substantive agenda focused on decolonization, moderating Cold War tensions, promoting nuclear disarmament, and pursuing greater equity in North-South relations. In the 1970s, the bloc increasingly attacked a world economy it perceived as fundamentally stacked against poor, developing nations. Under the influence of dependency theory, NAM members (as well as the parallel Group of 77) endorsed radical, redistributionist plans for a New International Economic Order—and the even more utopian vision of a New International Information Order. Neither scheme went anywhere, given resistance from the West, but the critique persisted, particularly as the “Washington consensus” triumphed in the 1980s. Politically, the NAM’s agenda focused on unredeemed national liberation movements, such as the anti-apartheid struggle and the Palestinian quest for statehood.

For good or ill, the NAM was an influential force in world politics during the Cold War. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has been a movement adrift. One possible ambition for the group, until recently, was to foil U.S. “unipolarity” and its (alleged) neoimperalist tendencies—typified by the “unilateral” invasion of Iraq and militaristic global war on terrorism. But the advent of a more conciliatory Obama administration, and the increasingly obvious diffusion of global power away from the United States, has undercut this narrative. Another NAM tack has been to rail against the inequities of a Western-dominated global economy. But these claims ring hollow in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, which has seen the United States, Europe, and Japan staggering under debt and struggling to regain growth, while much of the developing world (even sub-Saharan Africa) grows at an impressive clip.

The NAM today includes some of the world’s most dynamic economies, like Chile, Malaysia, and Singapore, not to mention four members of the Group of Twenty. India, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and Indonesia now have a curious split identity, with one seat at the “head table” of global economic governance and another in the NAM, alongside the likes of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, and Papua New Guinea. The NAM’s political diversity is equally striking, combining vibrant democracies devoted to human rights like Botswana and Panama with unreconstructed autocracies like North Korea, Sudan, and Zimbabwe.

Given this complex make-up, it is no surprise that the NAM faces increasing problems of coherence and cohesion. Agreement on basic principles like non-intervention and global economic justice is one thing, agreement on concrete plans of action and hard-hitting resolutions quite another. Accordingly, NAM summits tend to be glorified gabfests.

So why does the NAM persist? Undoubtedly, the tenacity of post-colonial mindsets, combined with a persistent belief that the structure of global politics remains stacked in favor of major powers, contributes. These dynamics are most clearly at play at the United Nations. The NAM members object to the exorbitant privilege enjoyed by the permanent membership of the UN Security Council (UNSC), the composition of which has not changed since 1945. To be sure, NAM members are deeply divided on how to reform the UNSC, but their resentment is palpable. (Similar criticisms apply to the structure of the main international financial institutions.)

Meanwhile, in the nuclear field, NAM members criticize the discriminatory nature of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). That treaty rests on a bargain between the nuclear haves and have-nots. In return for foreswearing such weapons, non-nuclear weapons states were assured under Article 6 of the NPT that nuclear weapons states would move steadily toward disarmament. That has not happened.

In this context, the unfortunate coincidence that Iran happens to be hosting this week’s NAM summit takes on grave significance. Many NAM members appear to buy Tehran’s argument that it is pursuing peaceful nuclear energy, as permitted under the NPT. Others may suspect Iranian nuclear weapons ambitions, but are annoyed at a Western (and particularly U.S.) double standard that sanctions Iran while ignoring Israel’s own nuclear program.

Iran, of course, is showcasing the event as evidence that—despite the best efforts of the United States and the West—it is not isolated diplomatically. The Iranians have set out an ambitious agenda, with sessions devoted to topics ranging from nuclear disarmament to UN reform, sustainable development, Palestinian statehood, human rights, and opposition to “unilateral” sanctions. But many attendees, particularly from the Arab world, have few illusions about Iran’s intentions and ambitions. This includes President Mohammed Morsi of Egypt, which lacks formal relations with Tehran.

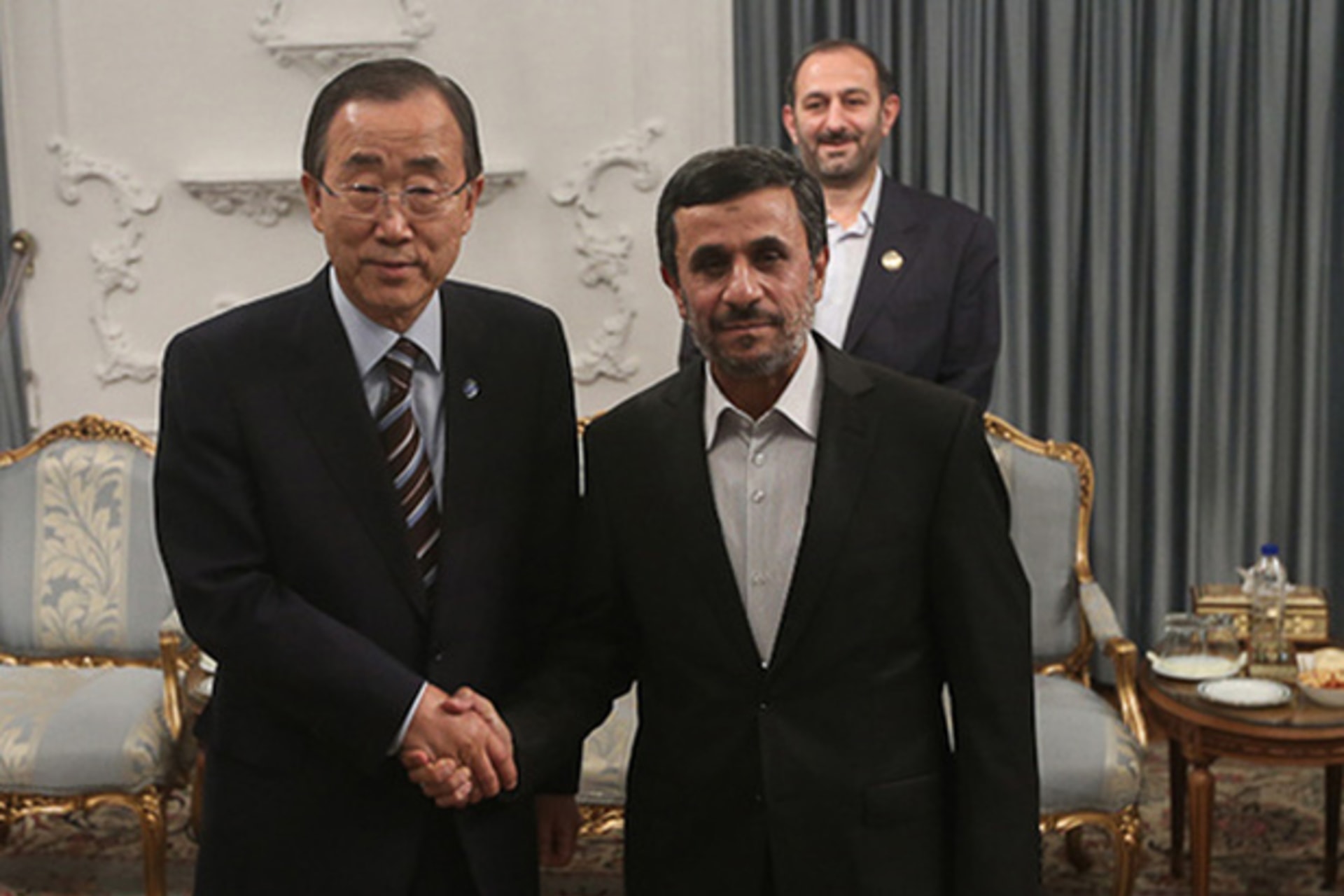

Both the United States and Israel have criticized the decision by UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon to attend the Tehran summit, arguing that his presence will hand a priceless propaganda victory to the Iranian regime and reduce the perception (and reality) of Iran’s diplomatic isolation. Ban’s determination to go is understandable, if unfortunate. Comprised of nearly two-thirds of UN member states, the NAM represents a huge constituency for the secretary-general. By declining to go, Ban no doubt fears, he would reinforce widespread perceptions that he is a tool of the West. But in choosing to attend, Ban has an obligation to hold the Iranian government to account for its behavior, by pointedly condemning its atrocious human rights record and its failure to cooperate with the IAEA and come clean about its clandestine nuclear weapons program. By failing to do so, he will make himself a useful idiot for the mullahs in Tehran.