ClimateWire (via The New York Times) reports that several key players are considering a push for a utility-only cap-and-trade system as part of an energy bill. That could be a wise move, if it’s done right.

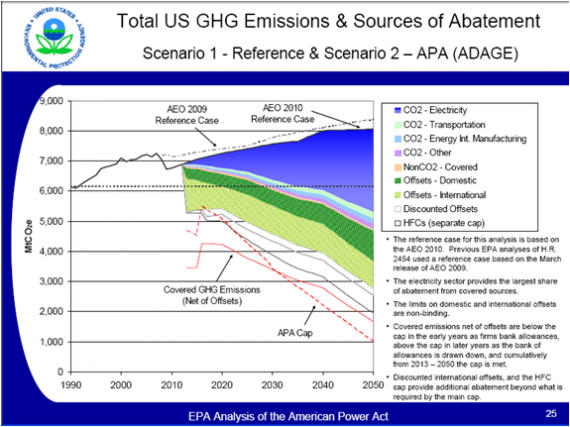

First the main substance. Take a look at this plot of emissions reductions under Kerry-Lieberman as projected by the EPA:

You’ll notice that almost all of the emissions reductions from U.S. energy use come from electric utilities, not just in the early years, but through 2050. Transportation, manufacturing, and “other” (my guess is mostly direct energy use in buildings) make up a very small fraction. A utility-only bill, then, should be able to get most of the reductions in U.S. emissions from energy use that an economy-wide bill would, but without some of the complexity and stigma. For this reason alone, utility-only should receive serious consideration.

Now for the potential problems. I can see at least four:

- The percentage cut in emissions from electricity generation would need to be substantially greater than the percentage cut in economy-wide emissions in order to achieve the same power-sector carbon price. (You’re cutting the same absolute amount off a much smaller base, so the fraction is bigger.) It may be complicated to explain why a target that looks much stronger than the 17% cut from 2005 levels by 2020 is actually no more onerous. If the result is a utility-only cap-and-trade with a 17% target for utilities, that will be a failure.

- Per the EPA graph, much of the emissions reductions in the EPA model of Kerry-Lieberman come from domestic and international offsets. A smaller-scale cap-and-trade system will almost certainly lead to lower demand for offsets. To the extent that the offsets represent real emissions reductions, utility-only would thus lead to lower emissions reductions. Similarly, to the extent that international cooperation is driven by financial flows from offset purchases, utility-only cap-and-trade would likely reduce such flows. This is not the end of the world, but it is not unimportant either.

- Many energy intensive manufacturers use electricity from the grid. If utility-only cap-and-trade increases the price of that electricity, but manufacturers don’t face direct limits on their own emissions, they may shift to lower-cost but dirtier on-site sources of energy, raising their emissions above business-as-usual and undermining the broader emissions control effort. Utility-only would thus need, at a minimum, to be accompanied by some sort of “no harm” efficiency standards for energy intensive manufacturing.

- The politics of cap-and-trade have traditionally involved using revenue from the transportation sector to compensate every other affected entity (utilities, manufacturers, consumers, etc). That is part of why so many business interests have been willing to support a bill. Utility-only doesn’t deliver that money. That may complicate the politics of a bill.

There is, of course, a fifth problem. It has been very tough to tie cap-and-trade to public outrage over the oil spill. A cap-and-trade system that deliberately does nothing about oil will be even harder to sell from that angle.