S&P’s Brazil Downgrade: Why it Matters

More on:

In a widely expected move, the ratings agency Standard and Poor’s (S&P) downgraded Brazil’s long term debt from a credit ranking of BBB to BBB- on March 24, bringing the country’s sovereign bonds a step closer to losing their “investment grade status” (defined as BBB- or above) and becoming "speculative" or “junk bonds.” The rating stems from a combination of indicators—including GDP growth, inflation, and external debt—that S&P uses to measure a country’s creditworthiness and its fiscal, regulatory, and political risks.

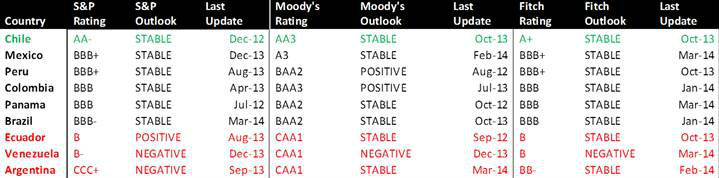

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, Latin America’s overall credit ratings have trended upward. By Fitch’s rating system, twelve out of fourteen Latin American countries have higher ratings today than a decade ago, one stayed put, and only one fell in the credit ranks. Chile sits at the top, reaching S&P’s AA- status (AAA status is the highest possible) in late 2012, on par with Japan and just above Israel. Mexico ranks next with a BBB+ rating (bumped up after its ambitious reforms passed); Peru too rates BBB+. At the bottom is Argentina with a CCC+ rating, improved from DDD after its 2001 default.

Before the recent S&P downgrade, Brazil’s sovereign credit rating ranked roughly in the middle of the region, on par with Colombia and Panama. S&P justified the downgrade based on the country’s “fiscal slippage”, its controversial accounting mechanisms, and the low likelihood that it will tighten spending before the October presidential election.

Does it matter? Many have questioned the importance of these scales, as well as the ratings agencies analytical independence. For Brazil, the downward shift had already been largely priced into domestic markets, and it seems to have had little effect in other nations. Further, the two other major agencies, Moody’s and Fitch, have yet to join their skeptical colleagues at S&P.

But before the government waves away the opposition critiques, they should reflect on the costs. Where it can and may matter is for Brazil’s companies, as corporate credit costs often follow sovereign rankings (known as the “sovereign ceiling”). In the twenty-four hours after Brazil was downgraded, S&P also lowered the ratings for two-dozen banks including Banco Santander Brasil and Itaú Unibanco. And studies show that highly-rated companies reduce investment after sovereign credit rating downgrades (though it affects lower-ranked companies less).

Dilma Rousseff may easily brush off any criticism and win a second term. Still, the downgrade could hinder her economic recovery plans. With Brazil turning increasingly to the private sector to fund much needed investments in ports, roads, and airports, a higher cost of capital for private domestic companies would give multinational firms a leg up over their Brazilian counterparts. And unlike in the recent past, Brazil’s public and development banks (BNDES and Caixa Econômica Federal) are unlikely to step in with abundant cheap loans, as they are already pulling back.

The downgrade also gives fodder to those talking about the divide happening in Latin America, characterized alternatively as between East and West, between a politicized Mercosur and the new Pacific Alliance, or generally between countries embracing world markets versus those pursuing a larger state role in the economy. S&P’s analysis reflects where they believe Brazil is leaning.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store