Steel Trade: How Trump Can Prove He's the Negotiator in Chief

More on:

On the eve of his first G-20 summit meeting, President Trump faces one of the most important decisions of his young administration: whether or not to impose tough restrictions on imported steel.

If he follows through on his threats, he will anger U.S. allies, defy powerful Republicans in Congress, harm big steel-using industries such as autos and construction, and likely roil financial markets that have so far been buoyed by his presidency. But if he walks away, he will be seen as abandoning a core campaign promise, and will demonstrate to both friends and foes that he is a paper tiger who can be pressured to stand down rather than make a tough decision.

Fortunately, for the president and the world, there is a third option that would prevent both of these harmful outcomes. President Trump should announce that he is suspending any immediate action on steel in return for a pledge by the large steel-making countries to pursue immediate and urgent negotiations to tackle the serious problem of overcapacity in the industry. He will reserve the right to take unilateral action if such negotiations fail, and set a deadline—perhaps six months—for the talks to show significant progress. In one stroke, Trump would demonstrate both firm resolve and a willingness to negotiate with other countries to solve pressing trade problems.

This model of using threats to induce cooperation is one that Republican presidents have deployed successfully in the past. In 1971, faced with a potential run on U.S. gold reserves, President Richard Nixon broke away from the fixed exchange rates of the Bretton-Woods system and levied a temporary 10 percent tariff on most imports. But he signaled immediately that he was prepared to lift the tariffs if other countries would negotiate on more favorable exchange rates, and four months later did so as Japan, Germany, and other countries fell in line.

And in 1985, again faced with an over-valued dollar, a fast-growing trade deficit and rising threats from Congress to block imports, President Ronald Reagan persuaded trading partners like Japan and Germany to revalue their currencies to deal with the growing imbalances. In both cases, negotiations and the threat of unilateral action solved real economic problems for the United States while largely avoiding damaging protectionism.

The Reagan approach is a better one this time. With America’s trading partners deeply worried about the U.S. tilt to protectionism, imposing tariffs immediately on steel is more likely to trigger retaliation than to induce cooperation. By holding off on immediate action, the president would re-assure allies and trading partners, while still making clear his determination to solve the problems plaguing trade in steel.

Here’s what President Trump should do. The Commerce Department is currently investigating, under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, whether steel imports are harming the U.S. defense industrial base in a way that threatens U.S. national security. While the premise is questionable since the military is a small steel user and most imported steel comes from trusted allies like Canada, Mexico, and South Korea, Section 232 has the virtue of giving the president great flexibility in deciding when and how to restrict imports.

Other tools are either limited or unusable. Conventional anti-dumping cases target specific products from specific countries, and are too easy to circumvent. And the so-called “safeguard” procedures, which were used by the George W. Bush administration to block steel imports in 2001, have been neutered by unfavorable rulings in disputes brought to the World Trade Organization.

Armed with a favorable Commerce Department decision, which is expected imminently, President Trump would then have a free hand. He could choose to block some or all steel imports, in whatever combination of products and from whichever countries he chooses. Given the size and importance of the U.S. steel market, that discretion would give him enormous leverage over the world’s steel-producing nations.

What should he do with that leverage? Secretary Wilbur Ross has said that if the administration acts, “it will be in the hope of provoking a collective solution by importing nations.” That is the right goal. Trump should announce that he is urgently convening a negotiation among all the major steel producing nations in order to force a reduction in the industry’s chronic overcapacity. The structure is already in place—G-20 leaders last December created the Global Forum on Steel Excess Capacity to address exactly such problems, but only strong U.S. action can make it meaningful. In particular, the United States should rally other G-20 steel producers both to address their own overcapacity and to increase pressure on China—which has heavily subsidized and rapidly expanded its steelmaking far beyond its domestic needs.

If the pressure succeeds, and China and other nations shut down steel mills to cut capacity—and not just offer promises to reduce capacity, which China has repeatedly failed to meet—then the United States would win without firing a shot. If the pressure on China does not succeed, the United States would at least enjoy greater international support for acting unilaterally, and lessen the likelihood of damaging retaliation. Indeed, it might be able to persuade other importing nations to put similar restraints on Chinese steel exports until Beijing agrees to tackle the problem with more urgency.

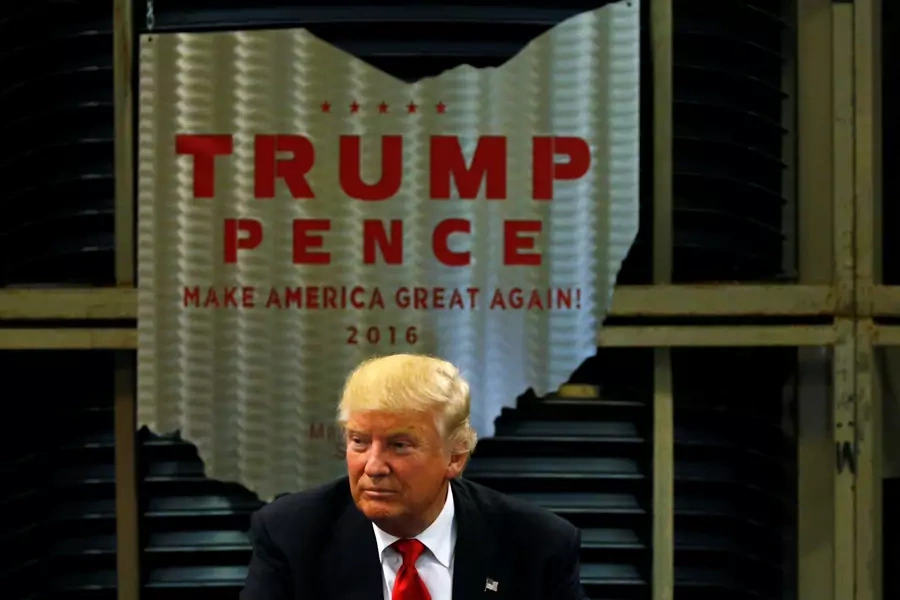

President Trump sold himself to the American people as a master negotiator who could get a better deal on trade and other issues. The steel decision represents the first real test of that claim.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store