Taking Stock of the Kenyan Election

With a divided electoral commission and legal challenges in the works, Kenya’s presidential election is neither the disaster some feared, nor the unambiguous success hoped for by champions of democracy.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Michelle GavinRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

By Michelle GavinRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

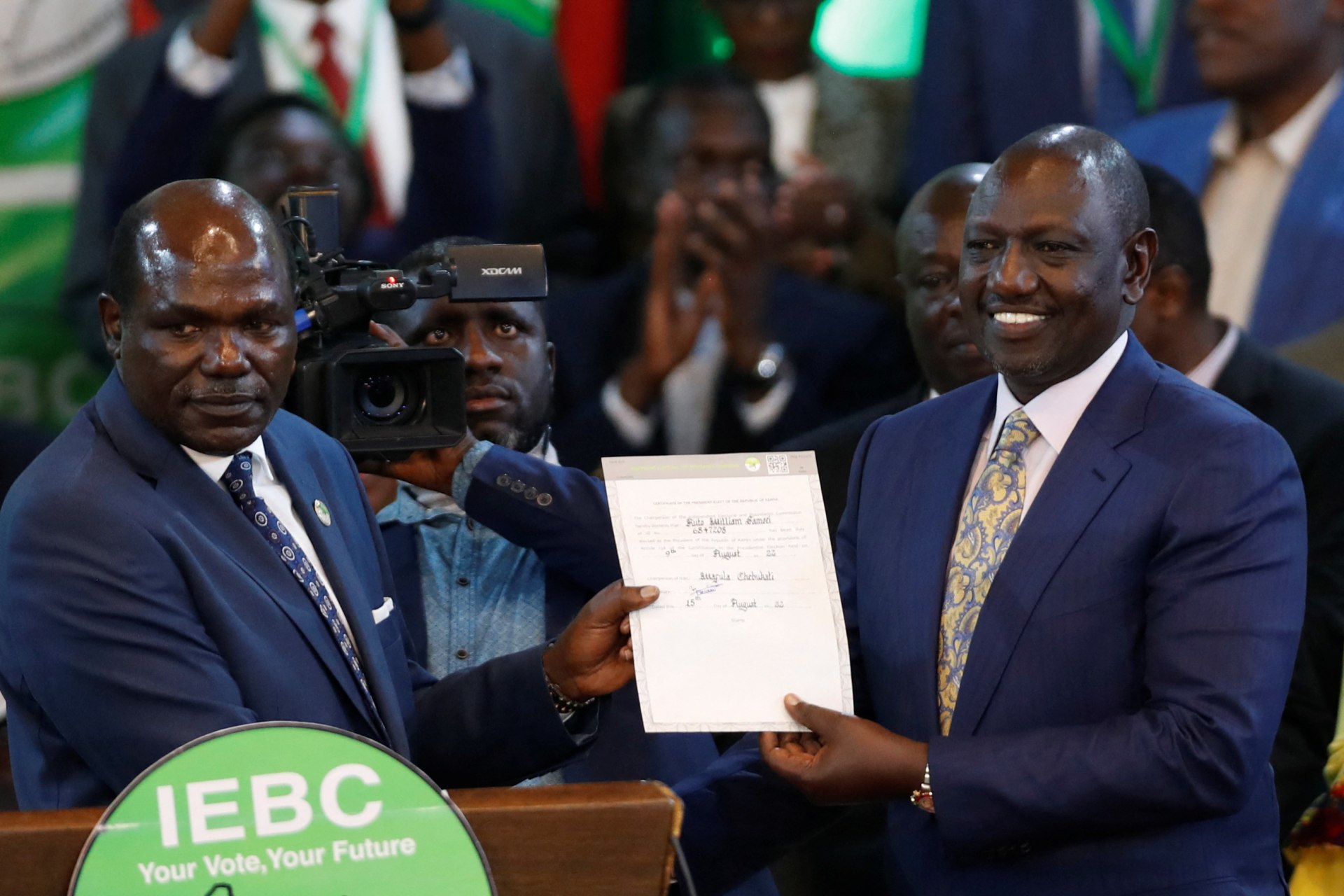

On Monday, Wafula Chebukati, the chairman of Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), announced that William Ruto narrowly beat out Raila Odinga to win the presidential election that occurred on August 9. The announcement came after days of speculation and uncertainty as the vote-counting dragged on. But rather than bringing definitive closure to Kenyans, the announcement may have kicked off a new phase of contestation.

Immediately before Chebukati took the microphone to announce the winner, scuffles broke out on the platform on which cameras were trained, revealing an incongruous scene of chaotic shoving while a choir continued to sing serenely in celebration of Kenya’s democracy. Four of seven IEBC commissioners, including the deputy chair, disowned the results at their own separate press conference. Incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta, who endorsed and campaigned for Odinga, has been notably quiet in the aftermath of the IEBC announcement. On Tuesday, Odinga indicated that he will pursue all available constitutional avenues to challenge the result, which he declared “null and void.”

While many African heads of state have extended warm congratulations to Ruto, the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi issued a cautious statement that stopped well short of that step. Administration officials are undoubtedly hesitant about getting out in front of Kenya’s own constitutional processes, particularly after John Kerry, as a leading election observer, came under withering criticism from some Kenyans in 2017 when his bullish comments before the Kenyan Supreme Court nullified the electoral result were perceived as one-sided at worst or premature at best.

The upshot is that thus far the electoral process has been both commendable and distressing. It’s true that Kenya held a massive and logistically complicated electoral exercise in an atmosphere of calm. Even those questioning the results are emphasizing the importance of maintaining the peace and using legal remedies, not violence, to address their concerns. It’s also true that important constituencies were less inclined to vote as cohesive ethnic blocks than in the past. But the notion that this election was “about the issues,” as Ruto has suggested, is not supported by the substance of the campaigning period. In what might have been an election about citizens’ desire for change, more transparency, and more accountability in government, both leading contenders held multiple and messy links to that current ruling class.

Certainly, it makes sense to let Kenya’s courts, which have demonstrated admirable independence in high-stakes moments like this one, bring clarity to legitimate questions about the electoral process. But it is hard to ignore the sense of exhaustion in Kenya after the long campaign and anxious wait for closure. The entire exercise may prompt relief in some quarters but is unlikely to renew confidence in Kenya’s democracy, which was already viewed with cynicism by a significant proportion of citizens, especially the large numbers of young Kenyans who declined to even participate in the voting. New reasons to doubt leaders’ legitimacy and institutions’ integrity only exacerbate concerns that the state is disconnected from and unaccountable to the Kenyan people. For champions of democratic governance, the news from Kenya induces an uncomfortable sensation, much like the dissonance brought on by a poised choir serenading a shoving match.

This publication is part of the Diamonstein-Spielvogel Project on the Future of Democracy.